My great-aunt Jettie appeared at my left and pushed my hair back from my face.

“Don’t worry, honey, things will work out. They always do.”

“Yeah.” I said, willing myself not to cry. Vampires, surely, didn’t blubber like little girls.

Aunt Jettie patted my head fondly. “There’s my girl.” I smiled up at her through watery eyes.

Wait. My great-aunt was dead. The permanent kind of dead.

“Aunt Jettie?” I yelped, sitting up and whacking my head against the wall behind me.

Note to self: Try to stop reacting to surprises like a cartoon character.

“Hey, baby doll,” my recently deceased great-aunt murmured, patting me on the leg—or, at least, through my leg. My first skin-to-ectoplasm contact with the noncorporeal dead was an uncomfortable, cold-water sensation that jolted my nerves.

Blargh. I shuddered as subtly as possible so as not to offend my favorite deceased relative.

Aunt Jettie looked great, vaguely transparent but great. Her luxuriant salt-andpepper hair was twisted into its usual long braid over one shoulder. She was wearing her favorite UK T-shirt that read, “I Bleed Blue.” The sentiment was horribly appropriate, all things considered. It also happened to be the shirt she died in, struck by a massive coronary while fixing a flat on her ten-speed. She looked nothing like the last time I saw her, all primped up in one of my grandmother’s castoff suits and a rhinestone brooch the size of a Buick.

Jettie Belle Early died at age eighty-one, still mowing her own lawn, making her own apple wine, and able to rattle off the stats for every starting Wildcats basketball player since 1975. She took me under her wing around age six, when her sister, my grandma Ruthie, took me to my first Junior League Tiny Tea and then washed her hands of me. There was a regrettable incident with sugar-cube tongs. Grandma Ruthie and I came to an understanding on the drive home from that tea—the understanding that we would never understand each other.

Grandma Ruthie and her sister Jettie hadn’t spoken a civil word in about fifteen years. Their last exchange was Ruthie’s leaning over Jettie’s coffin and whispering, “If you’d married and had children, there would be more people at your funeral.” Of course, at the reading of Aunt Jettie’s will, Grandma Ruthie was handed an envelope containing a carefully folded high-resolution picture of a baboon’s butt. That pretty much summed up their relationship.

Aunt Jettie, who never saw the point in getting married, was all too happy to have me for entire summers at River Oaks. We’d spend all day fishing in the stagnant little pasture pond if we felt like it, or I’d read as she puttered around her garden. (It was better if I didn’t help. I have what’s known as a black thumb.) We ate s’mores for dinner if we wanted them. Or we’d spend evenings going through the attic, searching for treasures among the camphor-scented trunks of clothes and broken furniture.

Don’t get the wrong idea. My family isn’t rich, just able to hold on to real estate for an incredibly long time.

While Daddy took care of my classical education, Jettie introduced me to Matilda, Nancy Drew, and Little Men. (Little Women irritated me. I just wanted to punch Amy in the face.) Jettie took me to museums, UK basketball games, overnight camping trips.

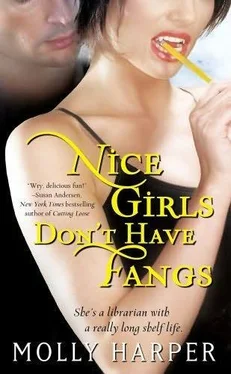

Jettie was included in every major event in my life. Jettie was the one who undid some of the damage from my mother’s “birds and bees” talk, entitled “Nice Girls Don’t Do That.

Ever.” She helped me move into my first apartment. Anyone can show up for stuff like graduations and birthdays. Only the people who truly love you will help you move.

Despite her age and affection for fried food, I was knocked flat by Jettie’s death. It was months before I could move her hairbrush and Oil of Olay from the bathroom.

Months before I could admit that as the owner of River Oaks, I should probably move out of my little bedroom with the peppermint-striped wallpaper and into the master suite. So, seeing her, crouching next to me, with that “Tell me your troubles” expression was enough to push me over the mental-health borderline.

“Oh, good, it’s psychotic-delusion time,” I moaned.

Jettie chuckled. “I’m not delusion, Jane, I’m a ghost.”

I squinted as she became less translucent. “I would say that’s impossible. But given my evening, why don’t you explain it to me in very small words?”

It was good to see that Jettie’s deeply etched laugh lines could not be defeated by death. “I’m a ghost, a spirit, a phantom, a noncorporeal entity. I’ve been hanging around here since the funeral.”

“So you’ve seen everything?”

She nodded.

I stared at her, considering. “So you know about my disastrous fourteen-minute first date with Jason Brandt.”

She looked irritated as she said, “’Fraid so.”

“That’s…unfortunate.” I blinked as my eyes flushed hot and moist. “I can’t believe I’m actually sitting here talking to you. I’ve really missed you, Aunt Jettie. I didn’t get to say good-bye before you…It was over so fast. I went to the hospital, and you were gone, and then Grandma Ruthie started talking about moving all of your stuff out of the house.

I felt so lost, and everybody just seemed to be talking over me—Mama and Grandma Ruthie, they just acted as if my opinion didn’t matter, even though I was the closest to you. And then the will was read, and Grandma Ruthie just lost her mind in the middle of the lawyer’s office and told me I had no right to the house, and it wasn’t supposed to go to me, and she was going to contest the will as invalid because you were obviously mentally incompetent. And I didn’t care about any of it, because none of it was going to bring you back—”

“Honey.” Aunt Jettie chuckled. “Take a breath.”

“I don’t need to anymore!” I cried.

In my years with Aunt Jettie, I’d learned to recognize her “trying not to laugh” face. She wasn’t even making an attempt at it. She was just rolling around on the ground, braying like a hyena.

“It’s not funny!” I cried, swatting through her insubstantial form.

Jettie continued to cackle while I pouted.

“It’s a little bit funny,” I admitted. “Dang it. Change of subject. Did you get to see your whole life played over instrumental soft rock before you died? What about your funeral? I didn’t get one, because no one knows I’m dead. But did you get to see your funeral?”

“Yeah.” Jettie grinned. “Great turnout. Shame about the suit, though. Couldn’t talk your grandma out of it, huh?”

I shrugged. “She wanted to send you to your grave with some semblance of decorum, or so she said.”

“I looked like Barbara Bush in drag,” Jettie snorted.

“Barbara Bush is dignified no matter what,” I offered. “Hey, if you’ve been here all along, why can I see you now?”

“Because I wanted you to see me.” Jettie seemed pained, brushing her icy fingers along my cheeks. “And because you’re different. Your senses have changed. You’re more open to what’s beyond the senses of normal, living people. I don’t know whether to be happy that you can see me or sad about what’s happened to you, sugar pie.”

I groaned. “See, now I know it’s bad, because the last time you called me sugar pie was right before telling me my turtle died.”

Awkward pause.

“So, what’s it like being dead?” I asked.

“What’s it like for you?” she countered.

I sighed, even though I didn’t have to, technically. “Unsettling.”

“Good word.” She nodded.

“What do you do? I mean, is there some sort of unfinished business I need to help you complete in order to move on to the next plane?”

Читать дальше