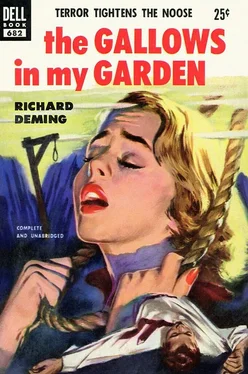

Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1953, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gallows in My Garden

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gallows in My Garden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gallows in My Garden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Actually, Moon got off one of the fastest snap-shots in history, and went on to wrap up the case for the most beautiful client he ever had.

Gallows in My Garden — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gallows in My Garden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You didn’t, Douglas! Say you didn’t!”

“But he did,” I put in before the doctor could speak. “Here’s another fact for you. Your husband’s death certificate shows a broken neck — no other injuries! Anyone whose head hit a windshield hard enough to break his neck would almost certainly have at least a brain concussion.” I turned my eyes on Douglas Lawson. “On the spur of the moment you took advantage of a perfect situation and killed your brother, didn’t you? I suppose you thought the chauffeur was unconscious, until he approached you a few months later and started nicking you for everything you had. Was that about how it happened?”

“How much can I sue this nitwit for, Jonathan?” Doctor Lawson drawled.

But Jonathan Mannering had his attention concentrated on me, and seemed unwilling to divert it.

“Your big brother was your father and childhood hero rolled into one, was he?” I shot at the doctor. “Or was he the overpowering guy who refused to let you work as he had, who sent you to medical school because he wanted you to go, who planned your life and thought he was being kind to his kid brother, but was only building within you a hate that ended in murder?”

I paused for breath. “After you started in practice you never saw much of your brother until he married the second time, did you? But when Ann became the hostess, you were a regular week-end guest. Your brother not only ran your life from infancy, he married the only woman you ever wanted, didn’t he? And when the opportunity was suddenly thrown in your lap, you murdered him.”

Doctor Lawson’s lips were still mocking, but his face was dead white. Every eye was turned on him. With an effort he lifted his own eyes to Ann, then swung them back to me.

“Go on with the rest of it,” he said softly.

“Probably you only wanted Ann at first. No doubt you knew the terms of the will, being so close to your brother, and figured the money was beyond your reach, anyway. Then Don started coming to you for treatment of imaginary ailments, and you recognized he had a psychotic personality. When the inspector and I interviewed you after the discovery of Don’s body, you made the statement that you were not a psychiatrist. Technically I suppose you’re not, but you had a year’s graduate work in psychiatry at your brother’s expense.

“About the same time Don started coming to you, Grace approached you with her marriage plans, and you suddenly saw a way to get both Ann and the money. Deliberately you encouraged the marriage, and you told Don he had an incurable disease — probably leukemia, since Don mentioned that disease to Arnold Tate.

“There’s no way of finding out how you worked on Don’s sensitive mind, but you managed to destroy it, and he plunged to his death. No court could convict you of murdering your nephew, but morally it was just as much murder as when you snapped your brother’s neck. You changed the suicide note because it pointed to what you had done. Would you like to hear what Don actually wrote before you cut half the note off with a pair of scissors?”

I produced Professor Quisby’s transcript and read it slowly. When I finished, the doctor’s sardonic smile had faded and sweat stood out upon his upper lip.

“You didn’t have to kill Grace,” I hammered at him. “All you had to do was expose her secret marriage. But if you exposed it yourself, Grace would never forgive you, and you were too fond of her to risk that. You mentioned it to Ann and found you were on delicate ground there, too, for if Ann suspected you were being unfair to Grace, she would have dropped you like a hot potato. This would have ruined your whole chess game, for your final move in getting your hands on the Lawson estate was to have been your marriage to Ann. And you couldn’t run the risk of exciting Ann’s suspicion that you were trying to make her an heiress.

“So you went to work on Arnold Tate. Mysterious attempts were made on Grace’s life, but strangely enough you were always around to block them. The first time, when the saddle girth broke, you even pointedly suggested someone had tried to kill her, a thought that hadn’t occurred to Arnold or Grace until you mentioned it. The falling flowerpot conveniently missed her by several feet, and as I remember, it was you who first noticed the strong odor of her milk, making sure she didn’t taste it.

“Then came the cut steering mechanism. Knowing Grace’s jolting method of leaving the garage, you assumed it would break immediately and no one would be hurt, but just to make sure you came along for the ride, so you could control the situation.

“But the swimming-pool incident was the masterpiece. Had she actually been thrown into the pool unconscious, Grace would have been bound to absorb some water, particularly if she were floating halfway to the bottom when you arrived, as you claimed. What really happened is that you simply dipped her in long enough to get her wet, pulled her out again, then yelled and dived into the pool.

“The clincher,” I went on, “is your bank account. You have twenty thousand dollars to your name. Yet you’ve had a large income from your practice for eleven years, and six months ago inherited fifty thousand dollars. I imagine your original deal with Garrity and Sommerfield was only to murder Vance Logan and stop the draining of your resources, but once you had them lined up, you decided to use them for miscellaneous purposes, like ridding yourself of troublesome bodyguards.”

Running out of words, I took a deep breath and asked, “Any important points I’ve left out?”

Dr. Lawson rose to his feet. His face was pale and his hands trembled, but his voice was still steady when he spoke.

“I think you’ve covered everything admirably, Mr. Moon. The only criticism I have to make is that it’s all hypothesis, just as you yourself admitted before you began.” His voice rose slightly. “And it’s all hogwash! You haven’t the faintest bit of evidence.”

“Never said I had,” I told him. “If I had evidence, you’d be in jail now.”

The doctor mustered a deprecating smile and turned to Grace. “You haven’t swallowed any of this rot, have you, honey?”

Grace cowered back against her husband’s shoulder. She made no reply, but the expression of horror with, which she regarded her uncle was enough answer for him. His smile flickered out, and his face suddenly became pinched. With the movements of a sleepwalker, he faced his fiancée.

“Ann,” he said simply.

She backed away from him, put both palms to her face, and burst into tears. Jonathan Mannering and Gerald Cushing simultaneously rose and approached her, making comforting noises from either side. Impatiently she shook them off, stared for a moment at Douglas Lawson as though at a stranger, then walked determinedly toward me.

“I hate you,” she said distinctly.

With that she burst into tears anew, rushed at Warren Day, and collapsed against his chest.

The inspector stood stiffly at attention, his arms held out from his body, at an angle as though to maintain balance. Above Ann’s bowed head his face was the color of stewed beets, and the look in his eye that of a cornered rabbit. One hand made an indefinite motion toward the weeping woman’s shoulder, then fell limply to his side before he could bring himself to administer a soothing pat. He remained in the same position, gaping like a fish, even after Ann suddenly left his inhospitable chest and disappeared into the house.

Douglas Lawson looked appealingly at Abigail Stoltz. She rose from her reclining position and followed Ann into the house without even glancing at the doctor. Without much hope he turned his eyes first to his friend Jonathan Mannering and then to Gerald Cushing, meeting nothing but a sort of horrified contempt in the face of either.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gallows in My Garden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.