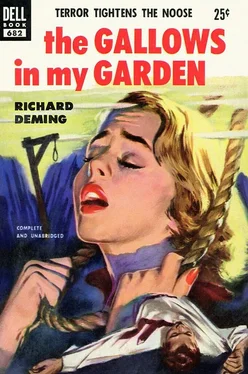

Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1953, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gallows in My Garden

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gallows in My Garden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gallows in My Garden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Actually, Moon got off one of the fastest snap-shots in history, and went on to wrap up the case for the most beautiful client he ever had.

Gallows in My Garden — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gallows in My Garden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You knuckle-head!” I yelled at him. “What am I supposed to do with an empty gun?”

“Guess I forgot to reload it,” he said mildly.

Fishing in his coat pocket, he produced a full clip. I traded him for the empty and went in without even saying thanks.

Possibly I was still jittery, for I opened my apartment door with the gun in my hand and the safety off. My dramatics proved unnecessary, however, for the place was empty.

I locked the door, opened all the windows, and in a few moments the place cooled off from boiling to a mere ninety-nine. After cleaning Mouldy’s pistol, taking a cool shower and a warm shampoo, I went to bed.

My mental alarm clock was off in the opposite direction the next morning. I set it for eight and woke at eleven. By the time I had shaved, dressed, and fixed myself eggs and coffee, it was noon.

I wore my green gabardine, which was the next lightest suit I owned after the tan one ruined by dust, and it was tailored snug through the chest. The bulge left by the .45 under my arm left little doubt about what I carried there.

The first thing I saw as I stepped out the main entrance of the apartment house was the yellow convertible parked across the street in the shade of an elm. When Mouldy saw me, he grinned like a dog wagging its tail. Resignedly I crossed the street, opened the car door, and climbed in.

“If I can’t get rid of you, you may as well chauffeur me,” I said. “How long you been waiting?”

“Since eight. Figured you wouldn’t be up before then.”

“Had lunch?”

“Three sandwiches.” He pointed to the drugstore on the corner.

“Drive me out to Willow Dale.”

We drove in silence for ten minutes before I asked, “Didn’t you tell Fausta I wanted you to let me alone?”

“Couldn’t. She wasn’t there.”

I lapsed into moody silence for the rest of the trip.

As I was showing Mouldy which drive to turn into, he said suddenly, “Joe, the bartender, said Fausta and that girl went off somewheres in a taxi.”

“What?” I yelled so loudly, he jammed on the brakes, nearly putting me on the hood.

“Don’t do that,” he said reproachfully, moving the car forward again.

As I started to open my mouth the second time, the Lawson swimming-pool came into sight, and I shut off what I had meant to say when I saw the two bathing-suited figures at the water’s edge.

“Stop by the pool,” I told Mouldy.

When he stopped, I got out and waved him on toward the parking-area behind the house. Then I crossed the short strip of lawn to stand with hands on my hips looking down at Fausta and Grace Lawson.

“She refused to stay at El Patio, Manny,” Fausta said quickly. “I could not keep her by force, so I did the next best thing. I went along.” I shifted my gaze to Grace.

“I couldn’t do it, Mr. Moon,” Grace said just as quickly. “I got to thinking if I had to suspect my own family and my closest friends, there’s not much point in living anyway. Then Don’s funeral was this morning, and everyone would have wondered where I was when all the rest of the family was there. It’s not Fausta’s fault. I made her let me go to the funeral and come home afterward.”

I didn’t say anything, because there wasn’t anything to say.

The Negro houseboy appeared around the edge of the weeping willows which screened us from the house. On a tray he carried two bottles of Coke and two glasses containing ice. As he neared, I noticed the tray also contained a shot glass of dark liquor, which I surmised to be rum, since rum and Coke is Fausta’s pet drink.

“Afternoon, sir,” he said to me.

“How are you, Edmund?”

Mixing Fausta’s drink first, Edmund handed it to her, then poured Grace’s plain Coke over the ice in her glass.

I asked Grace, “Is that boy of yours coming in tonight?”

“Arnold? He’s here now. We’re both so upset about this, we’re going to cut for a day or two. And we couldn’t go to class today anyway, on account of the funeral. Arnold’s up changing into swim trunks.”

I accompanied Edmund back to the house. Arnold Tate, wearing swim trunks and carrying a towel, was coming down the stairs as I started up.

“Let’s go up to your room for a minute,” I suggested.

His eyebrows rose, then he shrugged his lean shoulders and turned to lead me upstairs. Closing the door of his room behind us, I put my back against it.

“Sit down, Arnold,” I invited. “I have a question for you.”

Almost as though he knew what was coming, he perched himself on the side of the bed.

“There are five servants and six relatives and friends who might be responsible for the attempts on Grace’s life, Arnold. But of all of them, you’re the only one with an alibi for the time of Don’s death — presuming he was murdered, of course.”

He waited without saying anything.

“Isn’t that right?” I asked.

“You’re doing the talking,” he said without inflection. “I assume that’s a rhetorical question.”

I shook my head. “No. I want you to tell me your alibi.”

The fine bead of sweat on his brow could have been from the heat, but a light breeze moved the curtains, and I was not particularly uncomfortable in a coat. However, his voice was perfectly controlled.

“You lay excellent traps, Mr. Moon,” he said, “but I happened to phone my roommate that I was cutting today and tomorrow.”

I conceded the first hole.

“Then I’ll change my question. Where were you last Sunday night and early Monday morning?”

“No one asked me about it before, you know,” he said. “I never said I went back to school that night. Everyone else said I did, and I simply failed to correct the misapprehension. That’s hardly the same as lying, you know.”

I waved aside the distinction. “According to Grace she dropped you at the bus depot in time to catch the seven-fifteen, but you took the two a.m. That leaves nearly seven hours to explain.”

“Explain why?” he asked. “Since the police say Don was a suicide, no crime was committed during that seven hours.”

I regarded him steadily for a moment. “Maybe the police will ask the coroner to reconsider his verdict when they hear about your manufactured alibi.” I put my hand on the doorknob. “I’ll let you explain to Inspector Warren Day.”

“Hey, wait a minute,” he said. “I didn’t manufacture any alibi.”

“Tell the inspector that. Maybe he’ll believe you. I don’t.”

For a long time he regarded me broodingly. “All right,” he said finally. “It isn’t important enough to be stubborn about. I only kept quiet to save Grace and Ann any more grief than they already had. You see, I had an appointment with Don that night, and I know he committed suicide.”

I took my hand from the doorknob and blinked my eyes rapidly. “You mean you saw him?”

“Of course not!” he said impatiently. “That I would have told the police. And if I saw him, you think I’d have let his body lie down there in the sun for a week?”

“Take it in your own words,” I told him. “I’m temporarily out of questions.”

His face flushed almost imperceptibly, and he looked the slightest bit embarrassed. “It’s kind of silly, really. That Sunday Don got me aside right after dinner, and shortly before I was scheduled to leave with Grace, and asked me to meet him that night. He said he was in trouble and had to talk to me, but didn’t want Grace or anyone else to know. He wanted me to go in to the depot with Grace as planned, but instead of taking the bus I was to meet him at midnight at a tavern he named. They open at midnight Sundays, you know.”

I nodded to indicate I knew.

“I didn’t really want to talk to him, for to be frank, I never particularly liked Don. But after all he was Grace’s brother, and I felt some obligation to help him if I could. He seemed so deadly serious about it, I was impressed despite the sophomoric intrigue involving our clandestine meeting. So to make a long story short, I met him as he proposed. I presume he waited until eleven, when everyone in the house would be asleep normally, then sneaked out and caught the eleven-ten local bus that goes right past the house.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gallows in My Garden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.