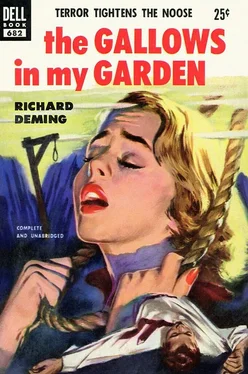

Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Richard Deming - Gallows in My Garden» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1953, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Gallows in My Garden

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Gallows in My Garden: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Gallows in My Garden»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Actually, Moon got off one of the fastest snap-shots in history, and went on to wrap up the case for the most beautiful client he ever had.

Gallows in My Garden — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Gallows in My Garden», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Only Abigail Stoltz and Gerald Cushing seemed willing to be kept in the dark. Very bluntly I threw cold water on the first four’s plans.

“Possibly one of the servants is engineering whatever is going on,” I told them. “But if Don’s death was actually murder instead of suicide, the murderer is a lot smarter than any of the servants seem. Right now I’m plugging for one of you six people being the engineer. Aside from myself and Grace, no one is going to know where she is.”

This shut up everybody but Grace. “I think Arnold ought to know,” she put in timidly.

“Suppose he’s the murderer?” I asked sourly.

“Oh, but Arnold couldn’t be!”

“Could Mrs. Lawson?”

“Of course not!”

“Or Doctor Lawson?” I asked wearily.

“Of course not,” she said less convincingly, and her eyes moved from one to the other of the rest of them.

Suddenly both palms flew to her face, and she began to cry.

Arnold Tate jumped to his feet. “Dammit, Grace,” he shouted at her. “We both know how to end this thing, and I’m going to do it right now!”

Grace’s tears stopped as suddenly as if a valve had been closed. The look she threw at Arnold was so frightened it was almost cowering.

“Don’t, Arnold! Please don’t. I’ll go away with Mr. Moon, and everything will be all right.” She smiled tremulously at the rest of us. “It hasn’t anything to do with all this. Nothing at all.”

Arnold strode into the house, slamming the screen door behind him. I made a mental resolution to speak to Arnold privately at the earliest opportunity.

After dinner we called a taxi instead of taking one of the other cars, because I had no intention of returning that night. Deliberately I left the impression I would not be back because our trip involved considerable distance, but actually I wanted some free time to do a little research at the state university.

To get to El Patio by the shortest route, we should have turned right when we left the Lawson grounds. But on the principle that overcaution is smarter than carelessness, I told the taxi driver to turn left. We had not gone more than three blocks in the wrong direction when I spotted a black sedan attempting to be inconspicuous a half block behind us.

“Union Station,” I told the cabbie.

When we reached the railroad station, I carried Grace’s suitcase and my own grip through the Market Street entrance. I had lost sight of the sedan after we entered downtown traffic, and in the mob at Union Station it was impossible to tell if anyone was following us.

A check of the train schedule board showed a train due to pull out north in ten minutes. I bought a one-way and a round-trip coach to a town a hundred miles north.

Our gate was number ten. Five minutes before train time we passed through it, but instead of going on to the train immediately, I led Grace to one side and peered through the iron railings at the bank of ticket windows in the main lobby. A squat, bowlegged man in a white suit stood at the window I had just left. Possibly it was coincidence, I thought, but from a distance and from the back he looked remarkably like the smaller of the two gunmen who had jumped me at my flat.

Six cars up I flashed our tickets at a conductor, and we climbed on the train. But instead of going into the coach, I left Grace standing in the vestibule with our luggage while I remained on the steps looking back at the gate. Just before the conductor shouted, “Board!” the short man in the white suit hurried through the gate and climbed into the last car. Even at that distance, there was no mistaking him. It was the short pal of the English lord.

Picking up our bags, I urged Grace on ahead of me through the car and on into the far vestibule. There I set down the bags, pulled open the door on the opposite side from which we had entered and tossed out our luggage. Without raising the floor platform over the steps, I dropped after the bags, then turned and held up my arms to catch Grace. The train gave a jolt and started to move just as I set her down.

“What are we doing, if you don’t mind?” Grace asked.

“Taking to water,” I said.

I scanned the windows of each car as it passed. Our shadow was in the last car, seated next to the window, and looked straight at us as the car rolled by. He wore one of the most startled expressions I have ever seen.

I gave him a friendly wave.

Crossing a set of empty tracks to the next loading-platform, which was for a train apparently just arrived, we mingled with the few stragglers still getting off and headed for the exit to the street. Seven empty taxis were lined up at the curb, there apparently being a momentary slump in the transportation business. I threw our bags into the first one.

“El Patio,” I told the driver.

El Patio, billed as “The Dining-Place of Kings” ever since a deposed monarch stopped there for a sandwich while passing through town, consisted of three huge rooms insofar as the public portion of it was concerned. The center one, originally a casino when the place was a gambling-house, was about the size of a first-class hotel lobby, and somewhat resembled one in that instead of the usual chrome and Bakelite furnishings stressed by cocktail lounges, comfortable sofas in front of which stood low coffee tables were spread through the room with planned haphazardness. The sofas, being the soft type you sink so far into you have to be a contortionist to get out again, were economic traps. They were so comfortable, and the effort involved in getting up again so tremendous, it was always less trouble to order another drink than to leave. And the lowest-priced cocktail El Patio served was a dollar and a quarter.

On one side of this room was the ballroom and on the other the dining-room where the ex-monarch munched his sandwich. Both were nearly as large as the cocktail lounge. Later in the evening all three would be jammed and standees would be three-deep at the bar, but at 2:30 on a Sunday afternoon the place was practically deserted.

As we passed through the cathedral-like bronze doors into the lounge, a thick-shouldered man with a skull nearly as flat as his face and a mild case of acne detached himself from the bar and approached with teeth showing in a grin.

“Hi, Sarge!” he greeted me, slamming a palm the size of a pancake griddle between my shoulder blades.

During the war Mouldy Greene, whose real name was Marmaduke, but derived the nickname “Mouldy” from his acne, had been the sad sack of my outfit, one of those soldiers whose well-meaning uselessness exasperated you to the point of wanting to boot him every time he stooped over while policing the area, but for whom you developed the same sort of protective fondness a mother feels for an idiot child. With an amazing lack of judgment El Patio’s former owner had hired him as a bodyguard, and Mouldy proved about as efficient a civilian as he had a soldier, managing to be out at the bar when his boss was murdered in his own office. Fausta Moreni inherited Mouldy along with the place, and having no use for a bodyguard, converted him to official customer greeter, a job which involved grinning at people as they walked in, after which he turned them over to the head-waiter. It was a perfect job for him, for in spite of his flat nose and mild acne, he had the same sort of appeal an ugly mongrel dog possesses, and people instinctively liked him. Fausta had almost broken him of the habit of pounding those he particularly liked on the back, but as an old army buddy he regarded me as above mere customers.

When I got back my breath, I said, “Hello, Mouldy. Fausta around?”

“In the office. Come on back.” His tone made it an offer of the whole building.

We followed him through the deserted dining-room and down a hall to an office, where we found Fausta working over the books.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Gallows in My Garden» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Gallows in My Garden» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.