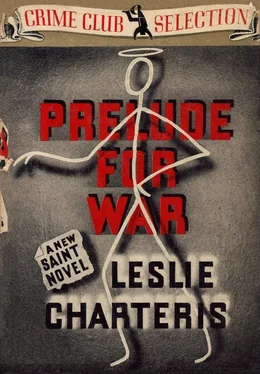

Leslie Charteris - Prelude for War

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - Prelude for War» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1938, Издательство: The Crime Club, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Prelude for War

- Автор:

- Издательство:The Crime Club

- Жанр:

- Год:1938

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Prelude for War: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Prelude for War»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Prelude for War — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Prelude for War», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

"I'd like to," she said sadly. "Especially after what you've done for me tonight — although if it comes to that, I expect you simply love dashing about rescuing people and doing your little hero act, so perhaps you ought to be a bit grateful to me for giving you such a good chance to do your stuff. And after all, if I just handed over the papers to you, that wouldn't do much good, would it? Of course, if you wanted to buy them—"

"To hell with buying them! Haven't you found out yet that there are some things in life that you can't measure in money? Haven't you realized that this is one of them? I don't know what there is in those papers — maybe you don't know either. But you must know that things like you've seen tonight don't get organized over scraps of paper with noughts and crosses on them — that men like Bravache and Fairweather and Luker don't take to systematic murder to stop anybody reading their old love letters. These men are big. Anything that keeps them as busy as this is big. Ana I know what kind of bigness they deal in. The only way they can make what they call big money, the only way they can touch the power and glory that their perverted egos crave for, is in helping and schooling nations to slaughter and destroy. What hellish graft is at the back of this show called the Sons of France I don't know; but I can guess plenty of it. However it works, the only object it can have is to turn one more country aside from civilization so that the market can be kept right for the men who sell guns and gas. Or else Luker wouldn't be in it. And he must know that there's an odds-on chance of bringing it off, or else he still wouldn't be in it. This may be the last cog in a machine that will wipe out twenty million lives, and you might have the knowledge that would break it up before it gets going. Doesn't that mean anything to you?"

She stood up slowly. And she freed her hands. "I think I'll be getting along now," she said, and her voice was quite steady in spite of the reluctance in it. "It's been a lovely party, but even the best of good times have to come to an end, and I need some sleep. Do you think you could move those men out of the bedroom while I put on some clothes?"

Simon looked at her.

The fire that had gone into his appeal was a glowing; ingot within him. It was a coiled spring that would drive him until it ran down, without regard for sentiment or obstacles. It was a power transformer for the ethereal vibrations of destiny. Earlier in the evening, the atmosphere of the Berkeley had defeated him; but this was not the Berkeley. He knew that there was only one solution, and there was too much at stake for him to hesitate. He was amazed at his own madness; and yet he was utterly calm, utterly resolute.

He nodded.

"Oh yes," he said. "I was going to move them anyway. I didn't think you'd want to keep them for domestic pets."

He went over and opened the bedroom door.

"Bring out the zoo," he said.

He stood there while the captives filed out, followed by Peter and Hoppy, and waited until the door had closed again behind the girl. For a few seconds he paced up and down the small room, intent on his own thoughts. Then he picked up the telephone and dialled the number of his apartment in Cornwall House.

Patricia answered the ring.

"Hullo, sweetheart," he said. His voice was level, too certain of its words to show excitement. "Yes… No trouble at all. Everything went according to plan, and we're all sitting pretty — except the deputation from the ungodly. Now listen. I've got a job for you. Call Orace and tell him to expect you. Then get out the Daimler, and tell Sam Outrell to pull Stunt Number Three. As soon as you're sure yon aren't followed, come over here. Hustle it… No, I'll tell you when you arrive. There are listeners… Okay, darling. Be seein' ya."

He put down the phone and turned to Bravache. The pupils of his eyes were like chips of flint.

"So you were going to kill Lady Valerie and blame it on to me," he said with great gentleness. "That was as far as we'd got, wasn't it? The Sons of France avenge the murder of one of their sympathizers, and all sorts of high-minded nitwits wave banners. Do you see any good reason why you shouldn't take some of your own medicine?"

"You daren't do it!" said Bravache whitely. "The Sons of France will make you pay for my death a hundred times!"

Dumaire's face was yellow with fear. Simon took him by the scruff of the neck and heaved him over to the window. He parted the curtains and pointed downwards.

"I suppose you came here in a car," he said. "Which of those cars is yours?"

The man shook like a leaf but did not answer.

Simon turned him round and hit him in the face. He held him by the lapels of his coat and brought him back to the window.

"Which of those cars is yours?"

"That one," blubbered Dumaire.

It was a small black sedan, far more suitable for the transport of unwilling passengers than the open Hirondel.

Simon released his informant, who tottered and almost fell when the Saint's supporting grip was removed. The Saint lighted another cigarette and spoke to Peter.

"You can use their car. Take them to Upper Berkeley Mews."

He looked up to find Hoppy Uniatz' questioning eyes upon him. There were times when Mr Uniatz had a tendency to fidget, and these times were usually when he felt that a very obvious and elementary move had been delayed too long. It was not that he was a naturally impatient man, but he liked to see things disposed of in the order of their importance. Now he grasped hopefully for the relief of the problem that was uppermost in his mind.

"Is dat where we give dem de woiks, boss?"

"That's where you give them the works," said the Saint. "Will you come outside for a minute, Peter?"

He took Peter out into the hall and gave him more detailed instructions.

"Did you hear enough while you were waiting to convince you that I haven't been raving?" he said.

"I always knew you couldn't be," Peter said sombrely, "because you sounded so much as if you were. I'm damned if I know how you do it, but it always seems to be the way."

"You'll see it through?"

"No," said Peter. "I'm going home to my mother." His face was serious in spite of the way he spoke. "But aren't you taking an unnecessary risk with Bravache and friend? Of course I'm not so bloodthirsty as Hoppy—"

The Saint drew at his cigarette.

"I know, old lad. Maybe I am a fool. But I don't see myself as a gangster. Do it the way I told you. And when you've finished, bring Hoppy back here and let him pick up the Hirondel and drive it down to Weybridge. You can stay in town and wait for developments — I expect there'll be plenty of them. Okay?"

"Okay, chief."

Simon's hand lay on Peter's shoulder, and they went back into the living room together. The Saint's new sureness was like a steel blade, balanced and deadly.

3

"You can't do this!" babbled Bravache. Little specks of saliva sprayed from his mouth with his words. "It is a crime! You will be punished — hanged. You cannot commit murder in cold blood. Surely you can't do that!" His manner changed, became fawning, wheedling. "Look, you are a gentleman. You could not kill a defenceless man, any more than I could. You have misunderstood my little joke. It was only to frighten you—"

"Put some tape on his mouth, Hoppy," ordered the Saint with cold distaste.

Pietri and Dumaire were gagged in the same way, and the three men were pushed on out of the flat and crowded into the lift. Simon left them with Peter and Hoppy in the foyer of the building while he went out to reconnoiter the car. It was nearly half-past two by his watch, and the street was as still and lifeless as a graveyard. The Saint's rubber-soled shoes woke no echoes as they moved to their destination. There was a man dozing at the wheel of the small black sedan and he started to rouse as the Saint opened the door beside him, but he was still not fully awake when the Saint's left hand reached in and took hold of him by the front of his coat and yanked him out like a puppy.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Prelude for War»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Prelude for War» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Prelude for War» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.