The voice was rich and crisp with candor. It was the kind of voice that knew what it was talking about, and automatically inspired respect. The professional voice. It was a voice which naturally invited you to bring it your troubles, on which it was naturally comfortable to lean.

Simon extracted a cigarette from the pack on the bedside table.

"I knew you wouldn't mind," he said amiably. "After all, I was only carrying out your own principles. You did what your instincts told you — and I let my instincts talk to me."

"Exactly. You are perfectly adjusted. I congratulate you for it. And I can only say I am sorry that our acquaintance should have begun like that."

"Think nothing of it, dear wart. Any other time you feel instinctive we'll try it out again."

"Mr. Templar, I'm more sorry than I can tell you. Because I have a confession to make. I happen to be one of your greatest admirers. I have read a great deal about you, and I've always thought of you as the ideal exponent of those principles you were referring to. The man who never hesitated to defy convention when he knew he was right. I am as detached about my own encounter with you as if I were a chemist who had been blown up while he was experimenting with an explosive. Even at my own expense, I have proved myself right. That is the scientific attitude."

"There should be more of it," said the Saint gravely.

"Mr. Templar, if you could take that attitude yourself, I wish you would give me the privilege of meeting you in more normal circumstances."

The Saint exhaled a long streamer of smoke towards the ceiling.

"I'm kind of busy," he said.

"Of course, you would be. Let me see. This is Thursday. You are probably going away for the weekend."

"I might be."

"Of course, your plans would be indefinite. Why don't we leave it like this? My number is in the telephone book. If by chance you are still in town on Saturday, would you be generous enough to call me? If you are not too busy, we might have lunch together. How is that?"

Simon thought for a moment, and knew that there was only one answer.

"Okay," he said. "I'll call you."

"I shall be at your disposal."

"And by the way," Simon said gently, "how did you know my phone number?"

"Miss Dexter was kind enough to tell me where you were staying," said the clipped persuasive voice. "I called her first, of course, to apologise to her... Mr. Templar, I shall enjoy resuming our acquaintance."

"I hope you will," said the Saint.

He put the handpiece back, and lay stretched out on his back for a while with his hands clasped behind his head and his cigarette cocked between his lips, staring uncritically at the opposite cornice.

He had several things to think about, and it was a queer way to be reminded of them — or some of them — item by item, while he was waking himself up and trying to focus his mind on something else.

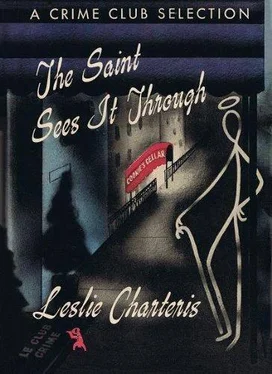

He remembered everything about Cookie's Cellar, and Cookie, and Dr. Ernst Zellermann, and everything else that he had to remember; but beyond that there was Avalon Dexter, and with her the memory went into a strange separateness like a remembered dream, unreal and incredible and yet sharper than reality and belief. A tawny mane and straight eyes and soft lips. A voice singing. And a voice saying: "I was singing for you... the things I fell in love with you for..."

And saying: "Don't go..."

No, that was the dream, and that hadn't happened.

He dragged the telephone book out from under the bedside table, and thumbed through it for a number.

The hotel operator said: "Thank you, sir."

He listened to the burr of dialling.

Avalon Dexter said: "Hullo."

"This is me," he said.

"How nice for you." Her voice was sleepy, but the warm laughter was still there. "This is me, too,"

"I dreamed about you," he said.

"What happened?"

"I woke up."

"Why don't you go back to sleep?"

"I wish I could."

"So do I. I dreamed about you, too."

"No," he said. "We were both dreaming."

"I'd still like to go back to sleep. But creeps keep calling me up."

"Like Zellermann, for instance?"

"Yes. Did he call you?"

"Sure. Very apologetic. He wants me to have lunch with him."

"He wants us to have lunch with him."

"On those terms, I'll play."

"So will I. But then, why do we have to have him along?"

"Because he might pick up the check."

"You're ridiculous," she said.

He heard her yawn. She sounded very snug. He could almost see her long hair spread out on the pillow.

"I'll buy you a cocktail in a few hours," he said, "and prove it."

"I love you," she said.

"But I wasn't fooling about anything else I said last night. Don't accept any other invitations. Don't go to any strange places. Don't believe anything you're told. After you got yourself thought about with me last night, anything could happen. So please be careful."

"I will."

"I'll call you back."

"If you don't," she said, "I'll haunt you."

He hung up.

But it had happened. And the dream was real, and it~was all true, and it was good that way. He worked with his cigarette for a while.

Then he took the telephone again, and called room service. He ordered corned beef hash and eggs, toast and marmalade and coffee. He felt good. Then he revived the operator and said: "After that you can get me a call to Washington. Imperative five, five hundred. Extension five. Take your time."

He was towelling himself after a swift stinging shower when the bell rang.

"Hamilton," said the receiver dryly. "I hope you aren't getting me up."

"This was your idea," said the Saint. "I have cased the joint, as we used to say in the soap operas. I have inspected your creeps. I'm busy."

"What else?"

"I met the most wonderful girl in the world."

"You do that every week."

"This is a different week."

"This is a priority, line. You can tell me about your love life in a letter."

"Her name is Avalon Dexter, and she's in the directory. She's a singer, and until the small hours of this morning she was working for Cookie."

"Which side is she on?"

"I only just met her," said the Saint, with unreal impersonality. "But they saw her with me. Will you remember that, if anything funny happens to me — or to her?... I met Zellermann, too. Rather violently, I'm afraid. But he's a sweet and forgiving soul. He wants to buy me a lunch."

"What did you buy last night?" Hamilton asked suspiciously.

"You'll see it on my expense account — I don't think it'll mean raising the income tax rate more than five per cent," said the Saint, and hung up.

He ate his brunch at leisure, and saved his coffee to go with a definitive cigarette.

He had a lot of things to think about, and he only began trying to co-ordinate them when the coffee was clean and nutty on his palate, and the smoke was crisp on his tongue and drifting in aromatic clouds before his face.

Now there was Cookie's Canteen to think about. And that might be something else again.

Now the dreaming was over, and this was another day.

He went to the closet, hauled out a suitcase, and threw it on the bed. Out of the suitcase he took a bulging briefcase. The briefcase was a particularly distinguished piece of luggage, for into its contents had gone an amount of ingenuity, corruption, deception, seduction, and simple larceny which in itself could have supplied the backgrounds for a couple of dozen stories.

Within its hand-sewn compartments was a collection of documents in blank which represented the cream of many years of research. On its selection of letterheads could be written letters purporting to emanate from almost any institution between the Dozey Dairy Company of Kansas City and the Dominican Embassy in Ankara. An assortment of visiting cards in two or three crowded pockets was prepared to identify anybody from the Mayor of Jericho to Sam Schiletti, outside plumbing contractor, of Exterior Falls, Oregon. There were passports with the watermarks of a dozen governments — driving licenses, pilot's licences, ration books, credit cards, birth certificates, warrants, identification cards, passes, permits, memberships, and authorisations enough to establish anyone in any role from a Bulgarian tight-rope walker to a wholesale fish merchant from Grimsby. And along with them there was a unique symposium of portraits of the Saint, flattering and unflattering, striking and nondescript, natural and disguised — together with a miscellany of stamps, seals, dies, and stickers which any properly conditioned bureaucrat would have drooled with ecstasy to behold. It was an outfit that would have been worth a fortune to any modern brigand, and it had been worth exactly that much to the Saint before.

Читать дальше