It gave him a queer feeling, somehow, after all that, to see her sitting down at the table of Dr. Ernst Zellermann.

Not that he had anything solid at all to hold against Dr. Zellermann — yet. The worst he could have substantially said about Dr. Zellermann was that he was a phony psychiatrist. And even then he would have been taking gross chances on the adjective. Dr. Zellermann was a lawful M.D. and a self-announced psychiatrist, but the Saint had no real grounds to insult the quality of his psychiatry. If he had been cornered on it, at that moment, he could only have said that he called Dr. Zellermann a phony merely on account of his Park Avenue address, his publicity, and a rough idea of his list of patients, who were almost exclusively recruited from a social stratum which is notorious for lavishing its diamond-studded devotion on all manner of mountebanks, yogis, charlatans, and magnaquacks.

He could have given equally unreasonable reasons why he thought Dr. Zellermann looked like a quack. But he would have had to admit that there were no proven anthropological laws to prevent a psychiatrist from being tall and spare and erect, with a full head of prematurely white and silky hair that contrasted with his smooth taut-skinned face. There was no intellectual impossibility about his wide thin-lipped mouth, his long thin aristocratic nose, or the piercing gray eyes so fascinatingly deep-set between high cheekbones and heavy black brows. It was no reflection on his professional qualifications if he happened to look exactly like any Hollywood casting director's or hypochondriac society matron's conception of a great psychiatrist. But to the Saint's unfortunate skepticism it was just too good to be true, and he had thought so ever since he had observed the doctor sitting in austere solitude like himself.

Now he had other reasons for disliking Dr. Zellermann, and they were not at all conjectural.

For it rapidly became obvious that Dr. Ernst Zellermann's personal behavior pattern was not confined to the high planes of ascetic detachment which one would have expected of such a perfectly groomed mahatma. On the contrary, he was quite brazenly a man who liked to see thigh to thigh with his companions. He was the inveterate layer of hands on knees, the persistent mauler of arms, shoulders, or any other flesh that could be conveniently touched. He liked to put heads together and mutter into ears. He leaned and clawed, in fact, in spite of his crisply patriarchal appearance, exactly like any tired businessman who hoped that his wife would believe that he really had been kept late at the office.

Simon Templar sat and watched every scintilla of the performance, completely ignoring Cookie's progressively less subtle encores, with a concentrated and increasing resentment which made him fidget in his chair.

He tried, idealistically, to remind himself that he was only there to look around, and certainly not to make himself conspicuous. The argument seemed a little watery and uninspired. He tried, realistically, to remember that he could easily have made similar gestures himself, given the opportunity; and why was it romantic if he did it and revolting if somebody else did? This was manifestly a cerebral cul-de-sac. He almost persuaded himself that his ideas about Avalon Dexter were merely pyramided on the impact of her professional personality, and what gave him any right to imagine that the advances of Dr. Zellermann might be unwelcome? — especially if there might be a diamond ring or a nice piece of fur at the inevitable conclusion of them. And this very clearly made no sense at all.

He watched the girl deftly shrug off one paw after another, without ever being able to feel that she was merely showing a mechanical adroitness designed to build up ultimate desire. He saw her shake her head vigorously in response to whatever suggestions the vulturine wizard was mouthing into her ear, without being able to wonder if her negative was merely a technical postponement. He estimated, as cold-bloodedly as it was possible for him to do it, in that twilight where no one else might have been able to see anything, the growing strain that crept into her face, and the mixture of shame and anger that clouded her eyes as she fought off Zellermann as unobtrusively as any woman could have done...

And he still asked nothing more of the night than a passable excuse to demonstrate his distaste for Dr. Ernst Zellermann and all his works.

And this just happened to be the heaven-saved night which would provide it.

As Cookie reached the climax of her last and most lurid ditty, and with a sense of supremely fine predestination, the Saint saw Avalon Dexter's hand swing hard and flatly at the learned doctor's smoothly shaven cheek. The actual sound of the slap was drowned in the ecstatic shrieks of the cognoscenti who were anticipating the tag couplet which their indeterminate ancestors had howled over in the First World War; but to Simon Templar, with his eyes on nothing else, the movement alone would have been enough. Even if he had not seen the girl start to rise, and the great psychologist reach out and grab her wrist.

He saw Zellermann yank her back on to her chair with a vicious wrench, and carefully put out his cigarette.

"Nunc dimittis," said the Saint, with a feeling of ineffable beatitude creeping through his arteries like balm; "O Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace..."

He stood up quietly, and threaded his way through the intervening tables with the grace of a stalking panther, up to the side of Dr. Ernst Zellermann. It made no difference to him that while he was on his way Cookie had finished her last number, and all the lights had gone on again while she was taking her final bows. He had no particular views at all about an audience or a lack of it. There was no room in his soul for anything but the transcendent bliss of what he was going to do.

Almost dreamily, he gathered the lapels of the doctor's dinner jacket in his left hand and raised the startled man to his feet.

"You really shouldn't do things like that," he said in a tone of kindly remonstrance.

Dr. Zellermann stared into sapphire blue eyes that seemed to be laughing in a rather strange way, and some premonitive terror may have inspired the wild swing that he tried to launch in reply.

This, however, is mere abstract speculation. The recordable fact is that Simon's forearm deflected its fury quite effortlessly into empty air. But with due gratitude for the encouragement, the Saint proceeded to hit Dr. Zellermann rather carefully in the eye. Then, after steadying the healer of complexes once more by his coat lapels, he let them go in order to smash an equally careful left midway between Dr. Zellermann's nose and chin.

The psychiatrist went backwards and sat down suddenly in the middle of a grand clatter of glass and china; and Simon Templar gazed at him with deep scientific concern. "Well, well, well," he murmured. "What perfectly awful reflexes!"

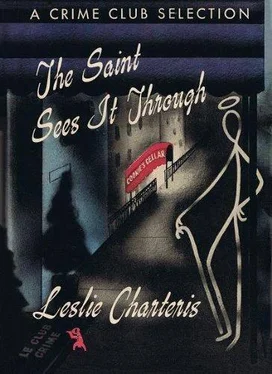

For one fabulous moment there was a stillness and silence such as Cookie's Cellar could seldom have experienced during business hours; and then the background noises broke out again in a new key and tempo, orchestrated with a multiplying rattle of chairs as the patrons in the farther recesses stood up for a better view, and threaded with an ominous bass theme of the larger waiters converging purposefully upon the centre of excitement.

The Saint seemed so unconcerned that he might almost have been unaware of having caused any disturbance at all.

He said to Avalon Dexter: "I'm terribly sorry — I hope you didn't get anything spilt on you."

There was an unexpected inconsistency of expression in the way she looked at him. There were the remains of pardonable astonishment in it, and a definite shadowing of fear; but beyond that there was an infinitesimal curve in the parted lips which held an incongruous hint of delight.

Читать дальше