"Yus, thank yer, miss."

"Gee, you must be English."

"That's right, miss." The Saint's voice was hoarse and innocent. "Strite from Aldgate. 'Ow did yer guess?"

"Oh, I'm getting so I can spot all the accents."

"Well now!" said the Saint admiringly.

"This your first time here?"

"Yus, miss."

"When did you get to New York?"

"Just got in larst night."

"Well, you didn't take long to find us. Do you have any friends here?"

"No, miss..."

The Saint was just saying it when a face caught his eye through the blue haze. The man was alone now in a booth which a couple of other seamen had just left, and as he shifted his seat and looked vacantly around the room the Saint saw him clearly and recognised him.

He said suddenly: "Gorblimy, yes I do! I know that chap dahn there. Excuse me, miss—"

He jostled away through the mob and squeezed unceremoniously into the booth, plonking his bottle down on the stained tabletop in front of him.

"Ullo, mite," he said cheerfully. "I know I've seen you before. Your nime's Patrick 'Ogan, ain't it?"

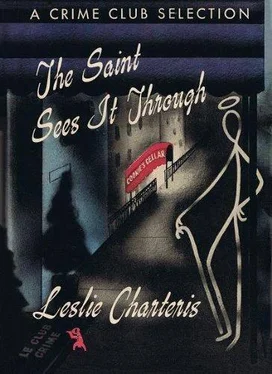

"Shure, Hogan's the name," said the other genially, giving him a square view of the unmistakable pug-nosed physiognomy which Simon had last seen impaled on the spotlight of Cookie's Cellar. "An' what's yours?"

"Tom Simons."

"I don't remember, but think of nothing of it. Where was it we met?"

"Murmansk, I think — durin' the war?"

"It's just as likely. Two weeks I've spent there on two trips, an' divil a night sober."

It appeared that Hogan found this a happy and satisfactory condition, for he had obviously taken some steps already towards inoculating himself against the evils of sobriety. His voice was a little slurred, and his breath was warmed with spicier fluids than passed over the counter of Cookie's Canteen.

"This 'ere's a bit of orl right, ain't it?" Simon said, indicating the general surroundings with a wave of his bottle.

"There's nothing better in New York, Tom. An' that Cookie — she's a queen, for all she sings songs that'd make your own father blush."

"She is, is she?"

"Shure she is, an' I'll fight any man that says she isn't. Haven't ye heard her before?"

"Naow. Will she be 'ere ternight?"

"Indeed she will. Any minute now. That's what I come in for. If it wasn't for her, I'd rather have a drink that'll stay with me 'an a girl I can have to meself to roll in the hay. But Cookie can take care of that too, if she's a friend of yours."

He winked broadly, a happy pagan with a girl and a hangover in every port.

"Coo," said the Saint, properly impressed. "And are yer a friend of 'ers?"

"You bet I am. Why, last Saturday she takes me an' a friend o' mine out to that fine club she has, an' gives us all the drinks we can hold; an' there we are livin' like lords until daybreak, an' she says any time we want to go back we can do the same. An' if you're a friend o' mine, Tom, why, she'll do the same for you."

"Lumme," said the Saint hungrily. "Jer fink she would?"

"Indeed she will. Though I'm surprised at an old man like you havin' these ideas."

"I ain't so old," said the Saint aggrievedly. "And if it comes ter 'aving fun wif a jine—"

A figure loomed over the table and mopped officiously over it with a checkered rag. The hand on the rag was pale and long-fingered, and Simon noticed that the fingernails were painted with a violet-tinted lacquer.

Hardly daring to believe that anything so good could be true, the Saint let his eyes travel up to the classical features and pleated golden hair of the owner of that exotic manicure.

It was true. It was Ferdinand Pairfield.

Mr. Pairfield looked at the Saint, speculatively, but without a trace of recognition; discarded him, and smirked at the more youthful and rugged-looking Hogan.

"Any complaints, boys?" he asked whimsically.

"Yes," Hogan said flatly. "I don't like the help around here."

Mr. Pairfield pouted.

"Well, you don't have to be rude" he said huffily, and went away.

"The only thing wrong with this place," Hogan observed sourly, "is all those pretty boys. I dunno why they'd be lettin' them in, but they're always here."

Then the truculent expression vanished from his face as suddenly as it had come there, and he let out a shrill joyful war-cry.

"Here she is, Tom," he whooped. "Here's Cookie!"

The lights dimmed as he was speaking, giving focus to the single spotlight that picked up the bulbous figure of Cookie as she advanced to the front of the dais.

Her face was wide open in the big hearty jolly beam that she wore to work. Throwing inaudible answers back to the barrage of cheers and whistling that greeted her, she maneuvered her hips around the piano and settled them on the piano stool. Her plowman's hands pounded over the keyboard; and the Saint leaned back and prepared himself for another parade of her merchandise.

"Good evening, everybody," she blared when she could be heard: "Here we are again, with a load of those songs your mothers never taught you. Tonight we'll try and top them all — as usual. Hold on to your pants, boys, and let's go!"

She went.

It was a performance much like the one that Simon had heard the night before; only much more so. She took sex into the sewer and brought it out again, dripping. She introduced verses and adlibs of the kind that are normally featured only at stag smokers of the rowdiest kind. But through it all she glowed with that great gargoyle joviality that made her everybody's broadminded big sister; and to the audience she had, much as the USO would have disapproved and the YMCA would have turned pale with horror, it was colossal. They hooted and roared and clapped and beat upon the tables, demanding more and more until her coarse homely face was glistening with the energy she was pouring out. And in key with his adopted character, and to make sure of retaining the esteem of Patrick Hogan, the Saint's enthusiasm was as vociferous as any.

It went on for a full threequarters of an hour before Cookie gave up, and then Simon suspected that her principal reason was plain exhaustion. He realised that she was a leech for applause: she soaked it up like a sponge, it fed and warmed her, and she gave it back like a kind of transformed incandescence. But even her extravagant stamina had its limit.

"That's all for now," she gasped. "You've worn me down to a shadow." There was a howl of laughter. "Come back tomorrow night, and I'll try to do better."

She stepped down off the platform, to be hand-shaken and slapped on the back by a surge of admirers as the lights went up again.

Patrick Hogan climbed to his feet, pushing the table out and almost upsetting it in his eagerness. He cupped his hands to his mouth and split the general hubbub with a stentorian shout.

"Hey, Cookie."

His coat was rucked up to his hips from the way he had been sitting, and as he lurched there his right hip pocket was only a few inches from Simon's face. Quite calmly and almost mechanically the Saint's eyes traced the outlines of the object that bulged in the pocket under the rough cloth — even before he moved to catch a blue-black gleam of metal down in the slight gape of the opening.

Then he lighted a cigarette with extreme thoughtfulness, digesting the new and uncontrovertible fact that Patrick Hogan, that simple spontaneous child of nature, was painting the town with a roscoe in his pants.

Cookie sat down with them, and Hogan said: "This is me friend Tom Simons, a foine sailor an' an old goat with the gals. We were drunk together in Murmansk-or I was drunk anyway."

"How do you do, Tom," Cookie said.

"Mustn't grumble," said the Saint. " 'Ow's yerself?"

"Tired. And I've still got two shows to do at my own place."

Читать дальше