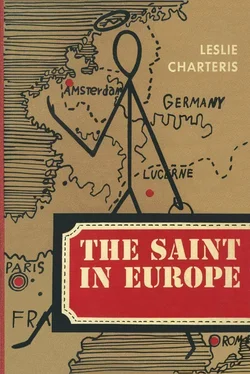

Leslie Charteris - The Saint in Europe

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - The Saint in Europe» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1953, ISBN: 1953, Издательство: Crime Club by Doubleday, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Saint in Europe

- Автор:

- Издательство:Crime Club by Doubleday

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-9997508201

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saint in Europe: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Saint in Europe»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Saint in Europe — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Saint in Europe», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Simon took the train because he had made the trip from Cologne to Mainz by boat before, and had announced himself a Philistine unimpressed. Reluctantly, he had summarized that much-advertised river as an enormous quantity of muddy water flowing northwards at tremendous speed under a litter of black barges and tugboats and pleasure steamers, with a few crumbling ruins on its banks shouldering awkwardly between clumps of factory chimneys. Scenically, it had been scanned and found wanting by the keen and gay blue eyes that had reflected every great river in the world from the Nile to the Amazon, even though he found the ruins a little pitiful, as if they had only asked to be left in the peace of years and had been refused. Also Simon took the train because it was quicker, and he had unlawful business to conclude in Stuttgart, which was perhaps the best reason of all.

For the saga of any adventurer take this: an idea, a scheme, action, danger, escape, and perhaps a surprise somewhere. Repeat indefinitely, with irregular interludes of quiet. Flavor it with the eternal discontent of unattainable horizons, and the everlasting content of an eagle’s freedom. That had been Simon Templar’s life since the day when he was first nicknamed the Saint, and it was his one prayer that he might be spared many years more in which to demonstrate the peculiar brand of saintliness which he had made his own. With valuable property burgled from an unsavoury ex-collaborationist’s house near Paris in his valise, and his fare paid out of a wallet picked from the pocket of a waiter who had made the mistake of being rude to him, the Saint lighted a cigarette and leaned back in his corner to be innocently glad that the lottery of travel could still shuffle a girl like that into the compartment chosen by a voyaging buccaneer.

She was very young — about seventeen or eighteen, he guessed — and her eyes were the bright greenish-blue that the waters of the Rhine ought to have been. She had pulled off her hat when she sat down, so that the unstudied symmetry of her curving honey-blonde hair framed her face in a careless aureole. She was beautiful. But there was something more to her than her mere unspoiled young beauty, something strange and startling that he could not define. She was the fairy princess that no man ever meets except in his most youthful dreams, the Cinderella that every man looks for all his life and knows he will never find. She was the woman that each man marries, only to find that he saw nothing but the mirror of his own hopes. And even when he had said that, the Saint knew that he had touched only a crude outline — that there was still something more which he might never be able to say. But because there seemed to be nothing of immediate importance in the newspaper he had bought at the station, and because even a lawless adventurer may find his own pleasure in the enjoyment of simple loveliness, Simon Templar leaned back with the smoke drifting past his eyes and wove romantic fantasies about the Rhine Maiden and the old man who was with her.

“This is der most vonderful river of der whole vorld, Greta,” said the old man, gazing out of the window. “For der Danube der is a valtz, but this is der only river in der vorld dot has four operas written about it. Someday you shall see it all properly, Gretchen — die Lorelei, und Ehrenbreitstien, und all kinds of vonderful places—”

An adventurer lives on impulse, riding the crest of life only because be takes the wave in the split second where others hesitate. The Saint said, quietly and naturally, with a slight movement of his hand, “I think there’s some better stuff over that way. Over around the Eifel.”

The other two both looked at him, and the happy eyes of the solid old man lighted up. “Ach, so you know your Chermany!” Simon wondered what they would have said if he had explained that the police of two nations had once hunted him up from Innsbruck through Munich to Treuchtlingen and beyond, on a certain adventure that was one of his blithest memories, but he only smiled. “I’ve been here before.”

“I know dot country, too,” said the old man eagerly, with his soft German-American accent faltering a little in his throat. “When I vos a boy we used to try and catch fish in der river at Gemünd, und vonce I get lost by myself in der voods going over to Heimbach. Now I hear der is a great talsperre , a big dam dot makes all der valley into a great lake. So maybe der is some more fish there now.”

It was as if he had suddenly met an old friend; the sluicegates of memory were opened at a touch, and the old man let them flow, stumbling through his words with the same naive happiness as he must have stumbled through the woods and streams he spoke of as a boy. There were many places that the Saint also knew, and a nod of recognition here and there was almost as much encouragement as the old man needed. His whole life story, commonplace as it was, came pattering out with a childish zest that was almost frightening in its godlike simplicity. Simon listened, and was queerly moved.

“...Und so I vork and vork, und I safe money and look after my little Greta, und she looks after me, und we are very happy. Und then at last I can retire mit a little money, not much, but plenty for us, und Greta is grown up.”

The eyes of the old man shone with a serenity that was blinding, the eyes of a man who had never known the doubts and the fretfulness of his age, whose humble faith had passed utterly and incredibly unscathed through the squalid brawl of civilization perhaps because he had never been aware of it.

“So now we come back to der Faderland to see my brother dot is a policeman in Mainz. Und Greta is going to see der vorld, und buy herself pretty clothes, und do all kinds of vonderful things. Isn’t dot all we could vant, Gretchen?”

Simon glanced at the girl again. He knew that she had been studying his face ever since he had first spoken, but his clear gaze turned on her with its hint of the knowledge veiled down almost to invisibility. Even so, it took her by surprise.

“Why... yes,” she stammered, and then in an instant her confusion was gone. She slipped her hand under the old man’s arm and rested her cheek on his shoulder. “But I suppose it’s all very ordinary to you.”

The Saint shook his head.

“No,” he said gently. “I’ve known what it is to feel just like that.”

And in that moment, in one of those throat-catching flashes of vision where a man looks back and sees for the first time what he has left behind, Simon Templar knew how far he and the rest of the world had travelled when such a contented and unassuming honesty could have such a strange pathos.

“I know,” said the Saint. “That’s when the earth’s at your feet, and you look at it out of an enchanted castle. How does the line go? Magic casements, opening on the foam. Of perilous seas in faery lands forlorn... ”

“There’s music in that,” she said softly. But he wondered how much she understood. One never knows how magical the casements were until after the magic has been lost.

She had her composure back — even Rhine Maidens must have been born with that defensive armour of the eternal woman. She returned his gaze calmly enough, liking the reckless cut of his lean face and the quick smile that could be cynical and sad and mocking at the same time. There was a boyishness there that spoke to her own youth, but with it there were the deep-etched lines of many dangerous years which she was too young to read. “I expect you know lots of marvelous places,” she said.

The Saint smiled.

“Wherever you went now would be marvelous. It’s only tired and disillusioned people who have to look for sensations.”

“I’m spoiled,” she said. “Ever since we left home I’ve been living in a dream. First there was New York, and then the boat, and then Paris, and Cologne — and we’ve scarcely started yet. I haven’t done anything to deserve it. Daddy did it all by himself.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Saint in Europe»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Saint in Europe» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Saint in Europe» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.