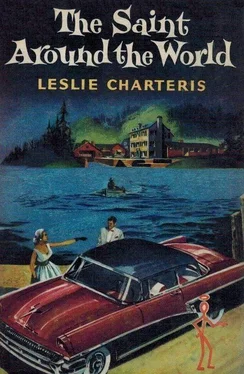

Leslie Charteris - The Saint Around the World

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Leslie Charteris - The Saint Around the World» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 1957, ISBN: 1957, Издательство: Hodder & Stoughton, Жанр: Крутой детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Saint Around the World

- Автор:

- Издательство:Hodder & Stoughton

- Жанр:

- Год:1957

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-9997508263

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Saint Around the World: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Saint Around the World»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Saint Around the World — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Saint Around the World», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The woman went out, lugging the heavy valise, with the manservant sauntering after her.

“Men starting to dig right now,” Tâlib said. “You wait. Very soon we know if you full of balloons. We dig up oil, Sheik Joseph make you rich sonofabitches. Not find oil” — he bared his teeth, and drew the back of the blade luxuriously across his throat before handing it back to its owner — “it’s too goddam bad, you betcha.”

He strode out, followed by the Negro, and lastly the guard with the submachine gun backed out and kept the room covered with it from the passage until the door was closed again.

“Lovable fellow,” drawled the Saint.

“What are we going to do?” whimpered the little man. “Did you see what he did? I know you only made it worse by telling them to tear up the Sheik’s garden. Now they’ll cut off our heads instead of just our hands.”

“I can’t see that it makes much difference, Mortimer. But Tâlib is probably exaggerating. We should have asked him what it says in the Koran about making divots in an Emir’s green.”

“And it wouldn’t do us any good to escape now. Even if we got out, we wouldn’t have any idea where to look for Violet.”

Simon lighted a cigarette.

“I don’t think we’re going to do any escaping for a while, anyway,” he said. “Didn’t you watch the valet character going through everything while the maid was packing up? And the Ethiopian who searched us didn’t even leave me my nail file.”

He had no reason to correct his hunch after they had gone over the apartment virtually inch by inch. Every article of metal that had a point or an edge or even a sharp corner had been neatly removed from their possessions. And when the first meal of their incarceration was brought to them, it was a reminder that in a country where the fingers were still the accepted eating utensil there would not even be the ordinary remote hope of secreting a fork or a spoon. As for the possibility of scratching away the very modern concrete in which the window ironwork was set with a shard from a broken dish, Simon could not even delude himself into giving it a trial.

“There must be something ,” persisted Mr Usherdown numbly.

“There is,” said the Saint, stretching himself out philosophically. “You can tell me the story of your life.”

That was about what it came to, for the next five days, and some of it was not uninteresting either, once the desperate need for any kind of distraction had got the little man started.

It may seem a shatteringly abrupt change of pace to suddenly condense five days into a paragraph, yet in absolute fact it would be nothing but outrageous padding to make more of them. Mr Mortimer Usherdown’s wandering reminiscences might have made a book of sorts by themselves, but they have no bearing on this story. Nor, in the utmost honesty, do the multifarious schemes for escape with which the Saint occupied his mind, since they were built up and elaborated only to be torn down and discarded, it would be a dishonest use of space for this chronicle to get any reader steamed up and then let down over them. It should be enough to say this time that if Simon Templar had seen any passable facsimile of a chance to make a break, he would obviously have taken it. But he didn’t. The main door of the suite was only opened twice each day, when their meals were brought, and each time the operation was performed with such efficient precautions that it would have been sheer fantasy to think that it offered a loophole. The Saint was realistic enough to conserve his energy for a chance that would have to come sometime.

It must be admitted, however, that when it came it was like nothing that he had dreamed of.

The first hint of it came around the middle of the sixth day, in the form of a vague and confused rising of noise that crept in on them even without any window that looked out on the front of the palace. When they noticed it, after the first idle surmises, they ignored it, then wondered again, then shrugged it off, then could not shut it out, then could only be silent and wonder, without daring to theorize in words.

It was an eternity later when the door was flung open, the four giant Negroes marched in, this time directed by Abdullah, and backed up by twice the usual detail of armed militia, and the Saint and Mr Usherdown were once again boxed in a square of Herculean muscle and marched headlong around the corridors and courtyards and corners that led back with increasing familiarity to the main forecourt. Since Abdullah spoke no English, it was useless to ask questions, although Mr Usherdown ineffectually tried to; and so they hurtled eventually through the grand portals into the ugly stifling heat and glare of the afternoon without any warning of what was to greet their eyes.

Simon was prepared for the tall skeletal pyramid of the oil derrick that now towered starkly amidst the withered remnants of Qabat’s only garden. The voices that he had heard from far off had also prepared him for the excited swarm of laborers, palace servitors, guards, and notables from the nearest mansions, who were milling vociferously around it. Nor was it surprising to see the Emir himself as a secondary focal point of the group, or Tâlib hovering behind him — or even Violet Usherdown standing near the Sheik, recognizable in spite of an orthodox veil by the copper curls which hung below a gold lamé turban which she had adopted.

What the Saint was incredulously unprepared for was the thick shining silvery column of fluid that shot up between the girders of the derrick and dissolved into a white plume of spray at the top.

For the first few dizzy seconds he felt only a foggy bewilderment at the color of it. Then as the observation forced itself more solidly into his consciousness he wondered deliriously whether he could have topped everything with the all-time miracle of bringing in a well that gave only pure refined high-octane gasoline. But in another moment his nose gave crushing refutation to that alluring whimsy. There was no smell of gas. And as his escorts wedged him through the encircling congregation and delivered him beside the Emir, at the very base of the scaffolding, a shower of drops fell on him, and he caught some on his hand and brought the hand right under his nostrils and then touched it with his tongue and knew exactly what it was.

It was water.

5

As if it had been only six minutes ago, instead of six days, Simon re-lived the capricious insubordinations of his mind, when he had been trying to concentrate on oil, and had been wafted through refineries to the ocean and through salads to irrigation, and it became clear to him that his latest discovered talent would need a lot more disciplining before it would be strictly commercial.

It also dawned on him that he was not his own only critic.

“Sheik know now, you one big goddam thief,” Tâlib bawled at him.

The Saint drew himself up.

In the superb unhesitating confidence of his recovery, he turned that flabbergasting moment into one of his finest hours.

“Tell Joe,” he said coldly, “that he is one big goddam fool.”

Mr Usherdown gasped, and even Tâlib blanched as he blurted out an indubitably expurgated rendition of that retort.

“I didn’t promise to find oil,” Simon went on, without waiting for the Emir’s reaction. “I can’t find it if it isn’t here, which you’ve already been told. I said I would make him rich. And I’ve done that. In Kuwait, isn’t water worth more than oil?”

As that was repeated, a hush began to fall, and even the Emir’s furious eyes settled into sharp and penetrating attention.

“Lots of places around here have oil,” said the Saint disparagingly. “But I’ve given Qabat something that none of the others have. I was told that Kuwait is spending forty-five million dollars to build a pipeline to get water. Won’t they be glad to save nearly two hundred miles of it and just bring the pipeline here, and give you the money instead? Is there any place around this Gulf that wouldn’t trade you ten barrels of oil for one barrel of water? Let Kuwait and Dharhan sweat out their oil, while in Qabat you take their money and buy beautiful cars and jewels and walk about in grass up to your knees.” He swept his arm grandly towards the jet of pure and glistening H 2O that was roaring merrily into the parched and burning sky. “This is what I’ve done for you, Joe.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Saint Around the World»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Saint Around the World» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Saint Around the World» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.