In half an hour, the Democratic candidate for senator of New York would be addressing this crowd, supposedly getting them stirred up, but right now that was hard to imagine, as he dropped dejectedly into the chair opposite me, slumping there.

Days ago I had heard about the funk Bobby was in from Bill Queen, the ex-NYPD cop and current Manhattan branch A-1 agent who was Kennedy’s personal bodyguard. Senatorial candidates didn’t get Secret Service protection, even when the candidate’s brother was an assassinated president.

Bill was also how I was able to get in to see Bobby without any red tape, a phone call getting me right to Steve Smith, Bobby’s campaign manager (and brother-in-law). And now I was sitting in the bedroom of a suite at the Statler — the venerable and very non-Space Age Statler in Buffalo, New York, that is. Not Dallas, out of which I’d flown yesterday afternoon.

About fifteen minutes ago, after working my way up from the lobby showing my ID to half a dozen interested parties, I’d entered the suite, where a bustling bunch of aides were in the outer area, some sitting, some pacing, almost all smoking. Included in this group was my man Bill, but also Steve Smith, the only guy in the room with his suit coat on, though his narrow red-and-blue striped tie was loosened.

Smith was a dark-haired, athletic-looking guy in his thirties, a former hockey goalie with a wry sense of humor and an unflappable nature. Like the others in this mostly male clubhouse (a few “Kennedy Girls,” secretarial types, all young and pretty, were tagging along with clipboards and pencils here and there), he was in shirtsleeves and looked frazzled for a guy normally cool.

The air was blue from cigarettes, so I said by way of greeting, “This must be that smoke-filled room I’ve heard so much about.”

“Nate,” Smith said, grinning. “Welcome to the monkey house.”

He looked a little bit like the young Joseph Cotten, though with a wider face. He offered a hand and I shook it, then he curled a finger for me to join him in as quiet a corner as the campaign hubbub would allow.

“Maybe you can get Bob out of his funk,” he said. “He likes you.”

“Doesn’t he like you anymore, Steve?”

“Right now he doesn’t like anybody much, including himself. This campaign has hardly started and we’re already getting kicked in the ass.”

My forehead frowned and my mouth smiled. “I can’t believe that. I mean, that guy Keating is well-liked enough, I guess, but he’s basically the smiling uncle you dodge at Christmas.”

Smith was shaking his head. “Don’t count Keating out. He’s a Republican but he’s a liberal one, and that makes him credible in this state. Good voting record.”

I nodded toward the street. “There’s a mob scene going on out there. They’re crazy about our blushing boy. Took me half an hour to push my way through.”

And it had — out on Delaware Avenue at Niagara Square, old and young, men and women, blacks and whites, strained against the police lines.

“Don’t be fooled,” Smith said. “A good share just want to see a Kennedy in the flesh — that’s no guarantee they’ll vote for him.”

“It’s a start.”

“Yeah,” he said with a humorless smirk, “but they haven’t heard him talk yet.” He spoke in a barely audible whisper. “Nate, the little fella’s been stinking on ice. He’s flat, and when he isn’t flat, he’s screechy. He’s nervous and he mumbles. Oh, he’s loud enough when he’s snapping at reporters, and you can sure hear that he’s got nothing bad to say about his opponent.”

“Doesn’t he want to win?”

The campaign manager shrugged in exasperation. “I don’t know at this point, Nate. I really don’t know. Maybe you can reason with him. I just know he’s blowing it.”

“So why bust your ass for the guy, Steve?”

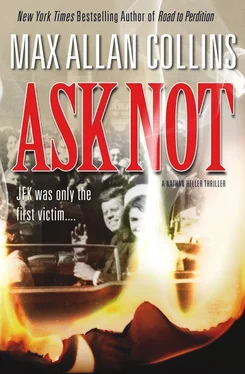

“Because Jean wants me to,” he said, referring to his wife, who was also Bobby’s sister, of course. “Anyway, it’s like I always say — ask not what the Kennedys can do for you, ask what you can do for the Kennedys... You can go on in, if you can get past your own man. Bobby knows you’re stopping by.”

Bill Queen was indeed sitting in a chair near the bedroom door, a bald mustached paunchy guy in his fifties in a brown suit and brown-and-yellow tie who was Central Casting’s idea of a cop, and Central Casting was right. He was reading Playboy magazine, or anyway looking at the busty blonde in the centerfold.

“Nice work if you can get it,” I said.

Unashamed, he refolded the Playmate and got to his feet. “I have a boss who can appreciate the finer things.”

I pointed to the magazine in his hand. “Those girls in there are young enough to be your daughter.”

“I don’t have a daughter, Nate.” He nodded toward the door and did Groucho with his eyebrows. “ He’s in a mood. Hell, he’s always in a mood. You shoulda warned me about the guy.”

“What mood would you be in, doing rallies on streets with high windows all around, if you were him?”

“Oh, that doesn’t faze Mr. Kennedy. Hell, he sits up on the backseat of a convertible like a beauty queen, waving and giving the crowd that sad-puppy smile. Sometimes he stands on the roof of a parked car to see ’em better. It’s like he’s askin’ for it.”

That sounded like Bobby. “So are Hoover’s boys cooperating?”

The ex-cop nodded. “I call them every morning, like you arranged, and they give me the latest death threats. Steady stream of ’em, Nate. Or do you think Hoover’s just trying to look vigilant for his old boss?”

“I don’t think J. Edgar gives two shits about what his ‘old boss’ thinks.”

Bill jerked a thumb at the closed door nearby. “Well, you tell your friend, in future, to listen to me about security measures, would ya? Then maybe I’d have better things to do with my time on this assignment than pound my pud in the john to Miss October.”

Bobby heard me come in and met me at the door, shaking my hand and giving me his shy, almost bucktoothed smile, which with his rather high-pitched voice suggested an Ivy League Bugs Bunny. “It’s been too long, Nate. Too long. Can I, uh, get you something to drink?”

I asked for a Coke and he yelled out to a Kennedy Girl to get us both one. She swiftly returned with a warm smile and two chilled bottles. Then she was gone and we were shut inside the hotel bedroom, which was smoke-free — Bobby was not a smoker, actually was adamantly against it, though he clearly didn’t forbid his staff. He wasn’t much of a drinker, either, as the sodas indicated, though he was by no means a teetotaler.

We exchanged a few pleasantries as I tried to get used to how skinny he looked. I hadn’t seen him since late October ’63, though I’d talked to him on the phone a few times, post-assassination, and he’d seemed himself. But in the flesh, he appeared to have shrunk, all but swimming in the white shirt and black trousers. Almost a year later, and he was still wearing black. His face seemed sunken, gaunt.

“Tell me, Nate, do you really have something to talk over with me, or, uh, did Steve Smith just want you to come and give me a pep talk — get me off my duff and into this thing?”

“I really do have something to talk about. And I don’t think it’s going to boost your spirits any. Just don’t jump out that window, when you hear. Anyway, some college girls down there would just catch you and drag you off to have their way with you.”

That made him smile, although his eyes lacked their usual spark. “Doesn’t, uh, sound half-bad.”

I gestured toward the muffled roar. “If you’re not up for this race, why the hell did you get in it?”

Читать дальше