I told her about Stanley Reed and Daniel and that I had their address. She pounced, near shouted,

“Shit, let’s go waste the fucker now.”

Well, you couldn’t fault her enthusiasm. I said, in a measured tone,

“This one is personal. The guy kicked the living shite out of me and I kind of want to pay back.”

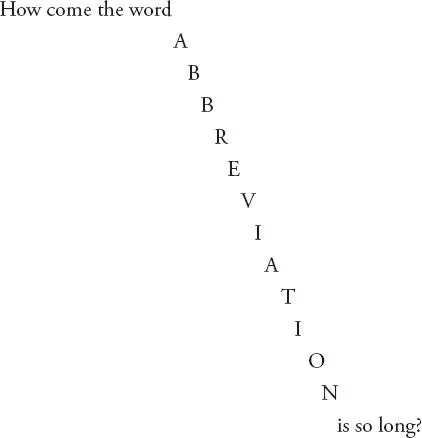

Payback.

Revenge.

Retaliation.

These were the walls within which she lived. She asked,

“What do you want me to do?”

Outlined the plan and she clapped her hands, said,

“I could go all Orphan Black ?”

“Discretion is the key here.”

“Long as I get to dress up.”

Then she paused, took a look at me, asked,

“What’s different with you?”

She always had an uncanny ability to home in on things, so I went deflection, said,

“Must be cutting back on the booze.”

Shook her head, then,

“Like you have an air of resignation. I was going to say surrender but that’s not in the Taylor songbook.”

Hmm.

I asked,

“So you and the Doc not an item anymore?”

She clinked the rim of her glass against her top teeth, a very irritating sound, said,

“I was just mind-fucking him.”

“Why?”

She seemed genuinely puzzled at this, then,

“Because I could.”

I said,

“Kind of cold.”

She stood up, laid a wad of notes on the counter, said,

“He was a bore and, like, I gave the poor bollix a dash of color. Where’s the downside?”

“I think he feels a bit of a loser.”

She laughed, loudly, said,

“Jesus, he was always that. I just brought it into focus.”

We set our plan for the boy and man and I asked her, earnestly,

“Can I rely on you not to fuck this up?”

She laughed, said,

“Oh, fuckups. Surely you have the lock on that, Jackie-boy.”

She had a point.

Back at my apartment, being under a death date, I could afford to be, if not magnanimous, then at least courteous. I had a bottle of sour mash, not easy to find in Galway but at McCambridge’s, the shop where the remnants of Anglo-Irish still lingered, you could find almost any hooch, at a price.

When it was busy, it was not unlike Ascot.

Hooray Henrys

In their faux Barbour coats.

Horsey women with sunglasses perched on their heads.

Dodgy solicitors dodging their dodgier clients.

And the new impoverished frat boys, once billionaires on paper and now not able to rub tuppence on a mortgaged tombstone.

The manageress, a rarity in Irish young women — she had a real accent, not the pseudo fucked American of Valley girls. She greeted,

“Jack, howyah?”

Not entirely sure why but that made me feel as if there are actually some things I might miss alongside breathing.

Thus armed, I knocked on Doc’s door. Took a bang or three but finally he opened the door a crack. Muttered,

“I gave at the office.”

I pushed my way in, proclaiming,

“Your time of whinging is up. She dumped you, get over it.”

He looked...

... fucking dreadful.

Only women can pull off the worn dressing gown look. And certainly no man of my generation can, if you’ll pardon the pun, carry off a box of tissues.

It’s just fucking gay.

So shoot me, the PC brigade.

His unshaven face looked like somebody squatted in his face and had bested all eviction notices. Oddly, his apartment was immaculate. I had noticed this before with Em’s mother, the lethal drinking coupled with an obsessive need to keep outward things in order, as if the chaos of the mind might be tempered by a severity of order in the surroundings.

Or, fuck,

... maybe they were just tidy.

I proffered the bottle and he asked, his voice a croak, a sure sign the vocal cords are out of use,

“We’re going American?”

I said,

“Seems to work for the government.”

He went to the kitchen, brought back two heavy tumblers, said,

“Part of a wedding gift.”

I lamely went,

“Oh.”

Deep, eh?

He said,

“There were six but I smashed them to smithereens to accessorize my new existence.”

He poured the booze and, as I looked around to sit, I tried,

“I’m sorry about you and... Em.”

He knocked back the shot like a good un, sneered,

“Don’t be a prick. You’re not sorry, not one fucking bit. You think it’s good enough for an old codger to get stiffed.”

Jesus.

I said,

“Well, in that case, tough shit.”

And...

He laughed.

We sat glaring at each other for a minute, then he said, cold voice,

“If there is nothing else, I need to get back to staring out the window.”

I stood and tried to come up with something Dr. Phil might provide.

Nothing.

I moved to the door and said,

“Hang in there, summer is coming.”

Fuck.

He gave a grimace, said,

“I’ve reached the tunnel at the end of the light.”

I had asked Em to pose as a Child Services officer and, if she could, to leave Reed’s house with the child Daniel.

If anyone could, she was the best bet. Five the next evening, I waited outside the house that Stanley Reed rented with the boy. Sure enough, a black Audi rolled up and out marched Em.

Dressed in a dark power suit, carrying a heavy briefcase, her hair severely tied back, and her face like the wrath of God, she strode up to the door and banged loudly. Stan opened and she bulldozed her way past him. I lit a cig, settled in to wait, but, to my amazement, the door opened after ten minutes and out came Em, leading the boy, who looked bewildered. Stan was waving his arms and Em turned sharply on a heel, got right up to his face, and read some riot act

... because he backed off.

She got Daniel into the car then pulled smartly out of there. I barely saw her face but I could have sworn I saw the beginning of a smile.

Okay, showtime.

I went around to the back of the house, jimmied the back door easily — no security but, then, when the monster is within, who needs locks? Into a cluttered hall, took a deep breath, took the revolver from my jacket, moved forward. Could hear Stanley screaming on the phone to, I presume, Child Services.

“... What the bloody hell do you mean you didn’t assign anybody, this is outrageous.”

I tapped him lightly on the shoulder.

He whirled around and I used the butt of the gun, broke his nose. He fell backward, the phone clattering on the floor. I said,

“That is a Galway hello.”

I picked up the phone, a voice leaking from it, like this:

“... Hello? Hello? Is anyone there?”

I said,

“Please hold, your call is important to us. For customer service, press 1.”

Reed was holding his nose, blood cascading along his impressively white shirt. He managed to focus, accused,

“I know you.”

I gave him my best smile, a blend of bitterness and devilry, said,

“You probably recall me best on the ground with your fucking shoe in my face.”

He said,

“The ferry.”

Then tried to figure out how to join the dots. Shaking his head, he said,

“I’m guessing the lady from Child Services wasn’t... from them?”

“Not much gets by you, unless you count the broken nose.”

He looked around, weighing his options, then,

“So what’s the plan, hotshot? You planning to shoot me?”

I pulled the hammer back, not for show as much as I relished the symbolism of that solid clunk, like a candle you light, thinking it carries significance. I said,

“Well, it is real simple. You leave town or you stay and see what I will do next.”

Читать дальше