‘Bet you won’t try that again in a hurry. OK, I should be able to sort you out. Hang on, let me get a pen.’

I offered up a silent prayer of thanks. Now there was an outside chance I could at least make the post-mortem. I checked my watch, gauging how much time I had left as the man came back on the phone.

‘Right, fire away. Whereabouts in the Backwaters are you?’

‘A place called Creek House. It’s not far from an old boathouse. Do you need directions?’

For a heartbeat he didn’t answer. ‘Don’t bother, I know it. You a friend of theirs?’

An edge had entered his voice, but I didn’t think anything of it. ‘No, they just gave me a tow. How soon can you get here?’

‘Sorry, can’t help you.’

For a second I thought I’d misheard. ‘But you just said you could come out.’

‘And now I’m saying I can’t.’

‘I don’t understand. Is there a problem?’

‘Yeah, you’ve got salt water in your engine.’

The line went dead.

What the hell...? I stared at my phone, unable to believe he’d hung up. The suddenly hostility had come out of the blue, as soon as I mentioned Creek House. I hit the steering wheel and swore again. Whatever issue the garage owner had with Trask, it had just cost me my last chance of making the post-mortem.

The headache was throbbing all the way from the base of my neck. Massaging it, I closed my eyes and tried to think what to do next. A dog’s excited barks made me open them again. A woman and a young girl were coming along the path through the copse, accompanied by a brown mongrel that pranced and yapped around them. The girl was precariously carrying a mug, holding it up as the dog bounced around.

‘... spill it! Naughty girl, Cassie,’ the girl was saying, but in a tone of voice that encouraged the dog even more. She was about eight or nine, with the same bone structure as her father and brother. Even though she was laughing, the thin arms and dark rings under her eyes suggested some underlying problem.

I assumed the woman must be her mother, although there was no obvious resemblance between them. She was slim and attractive, considerably younger than Trask. She had dark, honey-coloured skin and thick black hair tied casually back with a black band. Her jeans were faded and paint-stained, while the chunky sweater she wore looked at least two sizes too big. It made her look even younger, and I found it hard to believe she could have a teenage son.

‘We’ve brought you a coffee,’ the young girl said, carefully offering the mug she was carrying.

‘Thanks. Here, let me.’ I hurried to take it, giving her mother a smile. She returned it, but it was a token effort that vanished as soon as it came. She wasn’t conventionally pretty, her features were too strong for that. But she was undeniably attractive, with striking green eyes that were all the more startling against the olive skin. I found myself thinking that Trask was a lucky man.

‘Dad says you got stuck on the causeway,’ the girl said, looking past me at my car.

‘That’s right. I was glad he was there to tow me off.’

‘He says it was a bloody stupid thing to do.’

‘Fay!’ her mother admonished.

‘Well, he did.’

‘He was right,’ I said, smiling ruefully. ‘I won’t do it again.’

Trask’s daughter studied me. The dog had flopped down at her feet, grinning up at her with a lolling tongue. It was only young, hardly more than a puppy. ‘Where are you from?’ she asked me.

‘London.’

‘I know someone from London. That’s where—’

‘OK, Fay, let’s leave the gentleman alone,’ her mother cut in. She regarded me with a look that was cool rather than unfriendly. ‘How long are you going to be here?’

‘I don’t know. It looks like I picked a really bad day to break down.’ The weak attempt at a joke fell flat. I shrugged. ‘The garage in Cruckhaven won’t come out, so I’ll just have to wait for the recovery service.’

I saw her react when I mentioned the garage, but she made no comment. ‘When can they send someone?’

‘They can’t say. But I’ll be out of your way as soon as I can.’

The green eyes considered me. ‘I hope so. Come on, Fay.’

I watched them walk back to the house, Trask’s wife slim and poised as she rested her hand protectively on her daughter’s shoulder while the dog sprinted ahead. Well, that was blunt . I wondered if the inhabitants of the Backwaters were always this friendly, or if it was just me.

But I’d more to worry about than local hostility, so I soon put it from my mind.

The soft banks of the creek had been eroded away. Tides and currents had conspired to carve a sweeping arc out of the sandy earth, like a giant bite-mark flanked with reeds and marsh grass. It formed a natural trap, in which a variety of flotsam bobbed on the slow-moving water. Driftwood and twigs bumped alongside man-made detritus: a muddy training shoe, a doll’s head, plastic bottles and food containers, all caught in the circular eddy.

It was peaceful out here in the Backwaters. The world seemed ruled by gulls, marsh and water. And sky: the flatness of the landscape made it seem huge and vaulting. If I looked back the way I came, Trask’s house was just visible behind the copse of trees a couple of hundred yards away. I’d headed out along the creek after I’d finished the coffee. There was a path of sorts, not much more than a ribbon of bare earth worming its way through the tough and wiry grasses. It soon petered out, though, and I found it wasn’t possible to walk any distance without being diverted by another water-filled ditch or pool. It would be much easier in a boat, although even then I could imagine quickly becoming lost in this maze of saltmarsh and reeds.

I watched the swirling water nudge the trainer against a tennis ball without really noticing it. I’d been too restless to sit in my wet car while I waited for the recovery truck. I still hadn’t spoken to Lundy, but I knew the pathologist’s briefing would have already started. That wouldn’t take long, and then Frears would go ahead with the post-mortem whether I was there or not. Not that it would make any difference. I doubted I’d have been able to contribute much anyway. I was under no illusion about why I’d been included in the investigation, and my presence was even more redundant once Sir Stephen had identified his son’s belongings. Decomposed or not, confirming the ID and probable cause of death seemed likely to be a formality after that. Just as everyone had thought — with the possible exception of his father — Leo Villiers had killed Emma Derby, his estranged lover, and then cracked under the pressure and shot himself.

So why did I still feel uneasy?

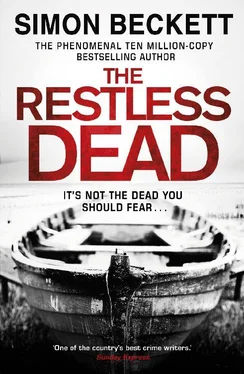

I looked out across the waterlogged landscape. Not far from where I stood, a derelict old boat lay stranded with its bow on the bank and its stern sunk into the water, crumbling and rotten. On the bank next to it was a dying willow tree. The bottom half of its thick trunk was stained, and strands of dead grass and weeds trailed from its lower branches as a reminder that the creek wasn’t always so sedate. It wasn’t hard to see how Leo Villiers’ body could have remained hidden for several weeks out here, sunk to the bottom of some deeper hole until it refloated and was carried into the estuary by the tide. It was a perfectly plausible scenario.

Except I still felt six weeks was too long for it to have played out in. Four, perhaps, but not six. Even if the body had remained on the creek bed for much of the time, it would still have been susceptible to the twice daily tides. It would have been dragged and pulled across the sandy bottom, bumped against rocks and stones, all the while subject to the depredations of whatever scavengers happened upon it. And during all that time its own internal decay would have continued, accelerating the body’s disintegration even more. I could tell myself that the cold water and air of the winter months would have preserved it, that estimating time-since-death wasn’t an exact science at the best of times, let alone in an estuarine environment like this. It didn’t matter.

Читать дальше