“I was going to call you first chance I got.”

“I’m too angry to even talk about how you’ve been avoiding my calls all day. We’ll deal with that later. Right now I need you to get out to Reston Park at the big pavilion.”

“A picnic?”

“Lucy Williams called me. She said I wasn’t to tell her parents about this. She wants to talk to you right away. Now get out there.”

She slammed her receiver down.

“Do you think Turk and I’ll get back together, Mr. C?”

I went over and put what I hoped was a brotherly arm around her and kissed her tear-warm cheek. “Sweetheart, you go through this every week. Of course you’ll get back together.”

She looked up at me with those guileless eyes and said, “Really?”

“Really.”

“Oh, thank you, Mr. C. Now I feel a whole lot better. Thank you so much.”

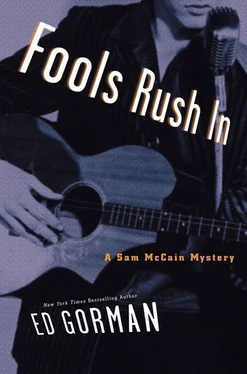

I was going to ask her not to be sobbing when she took the next phone call but who was I to interfere with, as Buddy Holly called them, true love ways?

The pavilion overlooked the river and a stretch of limestone cliffs that gleamed in the sunlight. The latest chromed and finned Detroit pleasure mobiles crowded around the structure itself. The smell of grilling burgers, the ragged laughter of three- and four-year-olds, a large portable radio playing Darlene Love’s “(Today I Met) The Boy I’m Going to Marry.” America, of Thee I Sing.

Lucy sat on a small boulder far upslope, where a fawn stood watching her from the woods. Instead of tennis whites she now wore jeans and a yellow blouse, her blonde hair long and loose in the wind sweeping up from the river below. She smoked a cigarette with great intensity and once, just as I approached and frightened the fawn away, touched a gentle hand to her temple, as if a headache had just struck.

“Lucy.”

I didn’t want to frighten her. But my call was worthless. She hadn’t heard me.

I walked closer. She turned, startled, and for just a moment seemed not to recognize me.

“Oh, God, Sam. It’s you.”

“I didn’t mean to scare you.”

She pointed a finger at her lovely head. “Migraine and — don’t ever tell my mother I mentioned this — my period. How’s that for God’s wrath?”

She’d meant the last as a joke. She’d even given me a momentary smile. But there was no humor in the tone or the smile.

“Why would God be punishing you, Lucy?”

“Because I killed David.”

Wind and the sound of a grass mower somewhere and downslope the delighted screams of the pavilion kids.

“You shouldn’t say things like that, Lucy. It could be dangerous.”

“It’s true, Sam.” Her eyes coveted my face, searching for even a hint of wisdom. But I was twenty-six-year-old Sam McCain and I had no wisdom.

“It’s not true, Lucy.”

“He wanted to break it off. He said he was destroying my life. He said that I didn’t have the strength to pull away but that he did. But I wouldn’t let him.” The tears came then, soft, soft as Lucy. “And they killed him. They said they would and they did.”

Face in hands, sobbing now, not soft, hard, hating his killers, hating herself.

“Who said they’d kill him, Lucy?”

She raised her small bottom up from the rock and pulled three small envelopes from her back pocket. As she handed them to me, she forced herself to stop sobbing. For moments, like a child, she couldn’t catch her breath. I didn’t look at the envelopes until I saw that she was all right.

Crude drawings of a stick figure hanging from a noose attached to nothing. And the words “Sambo has defiled the white race and he will die for it.”

All three were identical. The postmarks put them three days apart, all mailed from Cedar Rapids.

“I know who killed him, Sam, and it wasn’t that stupid biker.”

“Who do you think did it?”

Anger. “Goddammit, Sam, I didn’t say that I think. I said I know, all right?”

“All right. You know. Then tell me.”

“Rob and Nick.”

Simply Rob and Nick.

There were all sorts of ways to respond to what she said. But most of them would have just agitated her further. I went with “Tell me some more.”

She dug in the front of her jeans and pulled out a crumpled package of Winstons. She delicately plucked one free and then straightened it out before lighting it. The wind whipped away her first stream of smoke.

She was composed now. Hard, even. I’d never seen her this way. “Well, for one thing, they kept threatening to do it.”

“Both of them?”

“Both of them. Together and separately.”

“Drunk or sober?”

“Both.”

“Did they ever try anything?”

Another drag from her cigarette. “David had a little motor scooter. It wouldn’t do more than thirty miles’ an hour. He rode it back and forth between Iowa City and here on the nights when my parents wouldn’t give me the car. One night, when he was coming back from my house, they were parked in the woods and then they started following. They kept running him off the road. Scaring him. And he was scared. Then another night they got into his apartment in Iowa City and drew all kinds of terrible racist stuff on the walls.”

“You sure it was them?”

“Nick Hannity bragged about it.”

Fun guys, Rob and Nick.

“But killing is a long way from what you’re describing.”

“Nick beat him up in Iowa City one night. Badly enough that he had to stay overnight in the hospital.”

“Did he go to the cops?”

“Coming from Chicago? David wasn’t a big fan of cops.” The sunlight revealed the freckles across her nose and cheeks. A fetching touch of prairie girl. “There wasn’t much he could do. For one thing, we were both scared that the next time Rob and Nick did anything it’d be much worse.”

“You couldn’t tell your parents?”

“Are you kidding? They wouldn’t have taken Rob’s part but they would have nagged me about how this wouldn’t have been happening if David wasn’t a Negro.”

I got out a Lucky and lighted it. “Let me say something and don’t get mad.”

She smiled. A genuine smile. “I’m sorry, Sam. I can be a bitch.”

“You weren’t a bitch. You’re just understandably sad about David. But I need you to be rational and think clearly.”

She nodded. “I’ll try.”

“I have enough to go to Cliffie with, but with the connections Rob has he’ll be able to hide behind a lawyer. And besides, Cliffie has a boss now.”

“Cliffie has a boss?” A half smile. “He’s got to be a relative.”

“He is a she. But she’s not like other Sykeses. She eats with a fork and knife and never takes her dentures out at the table.”

She was enjoying this diversion. “God Almighty, can such a Sykes exist?”

“Jane is her name.”

“The new district attorney is a woman?”

“Not only a woman but a Brown grad. Honors from Brown and was second in her school class.”

“A Sykes?”

“A Sykes. A cousin. Old Man Sykes would have preferred a Sykes male, but he couldn’t find one smart enough for Dartmouth, which he’s got a fondness for because of some movie he saw when he was a kid. And Old Man Sykes got her elected because he knows how tired people are of Cliffie. Who, by the way, has improved considerably since he became a hero. I’ve got two uncles who were falling-down drunks and they’ve been on the wagon for about fifteen years each. I believe people can change.”

“Even Cliffie?” Then, frowning: “That’s what I meant about being a bitch. We make so much fun of him it’s hard to remember he’s a real human being. I suppose he can change. But he arrested that biker so quickly—”

Читать дальше

![Аманда Горман - The Hill We Climb [calibre]](/books/384311/amanda-gorman-the-hill-we-climb-calibre-thumb.webp)