“I just came out to buy some chickens.”

“You know where you can shove your chickens.”

“Any special reason you seem to hate me? Your sister and I were good friends.”

“Good friends, my ass. She’d still be alive if it wasn’t for you. She shoulda kept her nose out of it.”

I was marooned on the front lawn amidst a sea of gabby white chickens. The one-story house in front of me needed a coat of paint and the 1949 Pontiac up on blocks needed a left front door.

“She was murdered.”

“You think I don’t know that, McCain? That’s exactly what I told her would happen, butting in like that.”

They pecked, they squawked, they shat. Their heads jerked back and forth. They were pretty ugly creatures when you came right down to it. But you had to feel sorry for them. They had but one mission on this planet. To be consumed.

I worked myself through a clutch of them, drawing a few feet closer to the small, old house.

“If you know she was murdered, Debbie, you should want to help me.”

“And end up like she did?”

“Did she tell you what she saw?”

“No, she didn’t. I told her not to. I didn’t want to get caught up in all this crap.” She had a broad face that would have been attractive if she’d wanted to make it so with a little soap and makeup. But she was a widow — her husband had died in a freak accident with a combine — and a doggedly antisocial one at that.

“So you might as well get out of here, McCain. I don’t know nothing about what she saw or didn’t see. That’s between you and her.”

“She’s dead, Debbie. You’re the only one who can help me.” Then: “She saw something, Debbie. Something to do with the murders the other night. You were her best friend. She must have told you something.”

“I said that she didn’t, McCain. Now I’m going back inside and finish my lunch.”

And that was all. She turned, went back inside, and closed and locked the door behind her.

And left me with the chickens. Their squawks were putting me on edge. “How about keeping it down?” I said.

Which, of course, did me a lot of good. If anything, they seemed suddenly louder.

They trailed me back to my ragtop. A pied piper I was. I got in my car and started up the engine. I decided to go up to the far end of the road and take the blacktop back to town. Shorter route and less damage to the machine than on this scaly road.

I roared the mufflers three or four times. The chickens scattered. I didn’t want to grind one of them to death beneath my wheels.

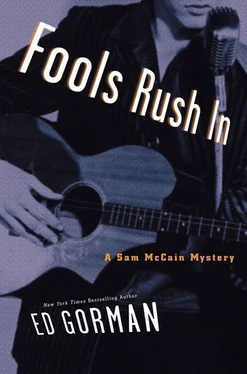

I set off, turning up the radio as I did so. The local stations still played Elvis’s “Return to Sender” from last year. I liked hearing Elvis sing just about anything, though I already missed his original sound when he was with Sun Records and covering songs like “Milk Cow Boogie” and “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” Hard to grow up out here without at least a sneaking fondness for real country music.

Also hard to grow up out here without a real desire to protect your blood kin. People like Debbie always bothered me. I just didn’t understand how you could write off a sister the way she had.

“I wouldn’t go in there if I was you.”

“It’s a public place, isn’t it?”

“Not really. Especially not to fuzz.”

“Technically, I’m not fuzz. I’m private.”

“Yeah, but you work for the judge. You know how many Devils she’s sent up?”

“Two, that I remember.”

“Well, you remember wrong. Four. And two of ’em are still doin’ time.”

The Iron Cross was a one-story concrete-block building that had been painted black, apparently to suit the mood of the bikers who drank there. At this hour of the day the front and sides of the place were packed with motorcycles. The jukebox inside trembled with gut-bucket rock and roll. And the laughter was of the coarse, ugly kind of pirates in all those buried-treasure movies.

The man I was talking to was named Ray Peters. He was a sort of honorary biker. He’d lost a leg and an arm in Korea and now got around on a single crutch. The word his brother gave me — his brother being a nonbiker who ran illegal crap games and was frequently in need of my legal services — was that Ray never felt right around “normal” people. So he dressed in a sleeveless denim jacket, jeans tucked into motorcycle boots, and an eyepatch he justified wearing by saying that his left eye had been damaged in Korea, too. He had one big problem that I could see. Take away the rebellion and what you had was a sad, lonely, and very decent guy.

“How about I do you a favor?” he said, as if to prove my point. His blond-gray hair was so thin on top the sun had already baked his scalp brick red.

“A favor?”

“You tell me who you want to see and I’ll go in and get him and see if he’ll come out.”

“Won’t that get you in trouble?”

A bleak smile. “Nah. They don’t pick on gimps till real late at night.”

“Nice folks.”

“They don’t pity me, anyway, McCain. And they don’t make fun of me. You take your nice, normal people — they wouldn’t let me fit in even if I wanted to.”

Even if some of that was paranoia, I knew how he felt. Or should I say I presumed to know how he felt? Being short and coming from the Knolls had made me into an outsider of sorts, too. But I was strictly a tourist. There was a French saying I’d picked up from a Graham Greene novel — “Embrace your fate.” I was pretty sure mine was a whole lot easier to embrace than poor Ray’s. He had to live his out every second of every moment when another human eye was on him.

“So who is it you want to see?”

“De Ruse.”

He laughed. “Man, you picked just about the meanest son of a bitch in the whole wolf pack. De Ruse. You sure you want to talk to him?”

“Yeah.”

“You packin’?”

“I’ve got my old .45 in the glove compartment.”

“Maybe you should transfer it to your coat. One of the guys who’s still servin’ time is his brother.”

“Good thing I’m a mean son of a bitch myself, huh?”

He laughed again. “I don’t know about mean. Crazy might be closer.”

He adjusted his crutch and said, “You sure?”

“I’m sure.”

When the door opened, a hurricane of dank smells violated the soft, sunny afternoon. Smoke, beer, whiskey, marijuana, and a toilet that the UN might cite as a weapon of mass destruction.

De Ruse came right out.

The muscles in his arms rippled like crawling snakes.

His green eyes gleamed with enormous malice.

He was alone.

He didn’t need anybody else.

He was strutting.

With his big loop earring and his bare chest and his red Indian-style bandana around his blond head, he looked like somebody who’d give Spiderman a whole raft of shit, Spidey being the only comic book I still read.

He threw the right hand from at least a foot and a half away. Given his short legs, just throwing it should have knocked him off balance. It didn’t. And traveling such a distance, and it being only one punch, its power should have been cut at least in half. It wasn’t.

There was quick, sharp, overwhelming pain, and then there was nothing.

I woke up sometime later with my wrists bound up in the necktie I’d been wearing and the rest of the tie wrapped around the rear bumper of my ragtop.

De Ruse was dragging me around the dusty lot of the Iron Cross to the great and abiding amusement of maybe twenty Road Devils.

The Road Devilettes, or whatever you called them, laughed especially hard. I knew right then and there that I probably wasn’t ever going to sleep with any of them, much as that was to be desired, with their beehive hairdos and witches’ brew cackles.

Читать дальше

![Аманда Горман - The Hill We Climb [calibre]](/books/384311/amanda-gorman-the-hill-we-climb-calibre-thumb.webp)