Partridge had a friend with him, a man who outweighed Sam Cragg by twenty pounds and most certainly had been either a prizefighter or wrestler at some time. He couldn’t have acquired such a battered face and such thick ears in ordinary encounters.

Sam began growling.

“Easy, boys,” said Jim Partridge. “I’m not looking for trouble. Not now. This is one of my operators. Call him Hutch.”

“The name is Hutchinson,” said Hutch. “Edgar Hutchinson. But don’t call me Edgar.”

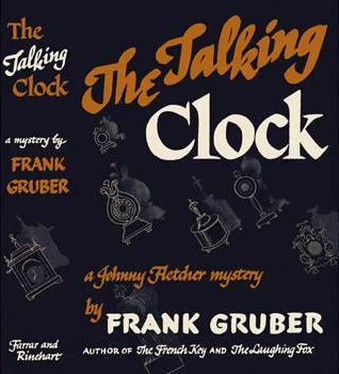

“Shut up, Edgar,” Partridge said. “Look, Fletcher, I see you’ve got a paper. You’ve read about the clock.”

“Just finished. Why’d you do it, Partridge?”

“The watchman’s description fits you birds.”

“We were sleeping at midnight.”

“That’s what the bell captain says. I asked him before we came up. But you might have slipped him something. He seemed to be on your side, all the way.”

“Eddie Miller? Yep, he practically works for me. So does Peabody, the manager. Get to the point, Partridge.”

“I am. You didn’t steal the clock and I didn’t. Who did?”

“Maybe it was an inside job. Your ex…”

Partridge glowered. “She’s not beyond it, but the watchman described these two pugs—”

“Maybe the watchman’s a friend of Bonita’s.” Johnny did not know how accurate was his guess.

“What’s he look like?”

“Don’t you know?”

Partridge grunted. “How should I? I’ve never been out there.”

“In Columbus you said you were representing the Quisenberry estate.”

“That was in Columbus. I’m working for myself, Fletcher.”

“Well, you want to watch yourself. You might forget and cut your own throat.”

Sam Cragg snickered and Partridge scowled. “Cut the comedy, Fletcher. I’m not ready to go out to the Quisenberry place yet. How’s about you running out there and finding out what’s what?”

“Uh-uh, Partridge. You look like a monkey all right, but we’re out of chestnuts today. I’m working for myself, too.”

“I’ve been thinking it over,” Partridge said, deliberately, “I’ve got an alibi for September 29th…”

Johnny looked pointedly at Hutch. “What was your ring name, Stupid?”

“Stupid?” yelped Hutch. “Why you—”

Sam Cragg took one step forward and hit Hutch on the side of the head with his fist. Hutch reeled to the wall, hit and ricocheted back. Sam clipped him on the chin, scarcely seeming to exert himself. Hutch fell to the floor on his face.

While this was going on, Johnny Fletcher stepped close to Jim Partridge, so he could block any move Partridge might make. Partridge watched what happened to his operator, his nostrils flaring. When Hutch hit the floor he said: “I guess I’ll have to fire him. He told me he could take it.”

“How about you, Partridge?” Sam invited. “You look pretty husky yourself…”

“I’ll wait till I’ve got some brass knuckles with me.”

Johnny gestured to Sam and the big fellow walked around behind Partridge and pinned his arms to his sides. Johnny relieved Partridge of his automatic. He scowled. “You’ve got some bullets today, I see.”

He slipped out the magazine and tossed it into the wastebasket. Then he proceeded to frisk Partridge further. He returned everything to the private detective’s pockets, except a crumpled telegram.

“Listen to this, Sam!” he exclaimed.

“ ‘James Partridge, Sorenson Hotel, New York. Collect Answer your wire. Not interested Smith and Jones. Inquest determined Quisenberry suicide. Fitch wound mere scratch. Besides this country has no money to send officer to New York, Doolittle, Sheriff Brooklands County, Minnesota.’ ”

“Why the rat!” snarled Sam Cragg.

“I thought there was something fishy about his threat. He didn’t have time to get himself an out-of-town alibi since last night and he wouldn’t have dared call us without a good alibi.”

“Shall I let him have it, Johnny?”

“You’re one up on me already,” Partridge replied. “Better not make it two.”

“I don’t get this telegram, Johnny,” said Sam. “How could a guy commit suicide by choking himself?”

“He didn’t. He was murdered all right. This hick county just doesn’t want to spend any money extraditing anyone and then prosecuting him. They’re taking the cheapest way out by calling it suicide.”

“Where’s the truck that hit me?” mumbled Hutch, sitting up.

Partridge kicked him in the ribs. “On your feet, Stumblebum!”

Knuckles massaged the door of Room 821 and Mr. Peabody’s voice called. “Mr. Fletcher, what are you doing in there? The guests are complaining about the racket you’re creating.”

Johnny opened the door. “Ah, good morning, Mr. Peabody. We were just doing our daily calisthenics…”

Peabody looked at Hutch who was climbing unsteadily to his feet.

“Our physical culture instructor,” Johnny said. “He comes every morning to give us a workout. See you tomorrow, eh, Professor?”

Jim Partridge grabbed Hutch’s arm and propelled him past Peabody, into the corridor. Peabody still glowered at Johnny.

“I knew I was making a mistake, Mr. Fletcher. You’re mixed up in something again…”

“Why, Mr. Peabody,” Johnny said, reproachfully. “I’m beginning to think you don’t appreciate guests who pay in advance, by the week…”

“Ah!” cried Peabody, throwing his hands into the air and turning away.

Sam Cragg kicked the door shut. It made a good loud slam. “Well, that settles that, Johnny. Since Minnesota no longer wants us, we can drop out of the Quisenberry business.”

“Why,” said Johnny, “if the law’s no longer interested in punishing a culprit, it’s up to the private citizen and you and I, Sam—”

Sam put his head between his hands and groaned. “Trouble, here we come again!”

They left the hotel ten minutes later and had breakfast at the orange stand on the comer, a glass of orange juice, two doughnuts and a cup of coffee. Finished, Johnny hailed a taxicab.

Sam grumbled as they got in. “A ten-cent breakfast and then a taxi…”

“We’re in a hurry. West Avenue, Cabby.”

“The clock man, huh?”

“That’s right. I want to see whether he looks happy or mad today. He was pretty keen about that clock yesterday.”

Twenty minutes later they climbed out of the taxi before a tall building, facing the Hudson River docks. Johnny paid the taxi bill, adding a nickel tip, over which the cabby muttered, then faced the building.

“Aegean Sponge Company,” he read the inscription on the brass plate beside the door of the building. “Nicholas Bos, President. You wouldn’t think they sold enough sponges in this country for that bird to pay seventy-five G’s for a fancy clock.”

They went into the building. A receptionist with buck teeth and a complexion like Roquefort cheese had them spell out their names, then telephoned them to an unknown person. After a moment she covered the mouthpiece. “What is your business?”

“Clocks,” said Johnny. “We met Mr. Bos in Hillcrest yesterday.”

The girl relayed the additional information, then nodded. The door beside her desk burst open and the olive-skinned Nicholas Bos reached out with both hands.

“Come in, gentlemen. I am so glad seeing you. Come in, please!”

They followed the sponge importer to an office which contained forty or fifty clocks, all of them showing the correct time, nine forty-eight.

Bos closed the door and turned eagerly to them. “Yes, gentlemen? You have gome to sell…”

“Sell what, Mr. Bos?”

“The clock maybe?”

“The Talking Clock?”

Nicholas Bos almost drooled. “You have it?…” he whispered.

Читать дальше

![Корнелл Вулрич - Eyes That Watch You [= The Case of the Talking Eyes]](/books/32103/kornell-vulrich-eyes-that-watch-you-the-case-of-thumb.webp)