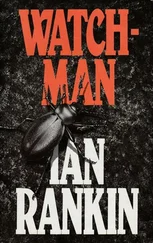

Ian Rankin

Bleeding Hearts

She had just over three hours to live, and I was sipping grapefruit juice and tonic in the hotel bar.

‘You know what it’s like these days,’ I said, ‘only the toughest are making it. No room for bleeding hearts.’

My companion was a businessman himself. He too had survived the highs and lows of the ’80s, and he nodded as vigorously as the whisky in him would allow.

‘Bleeding hearts,’ he said, ‘are for the operating table, not for business.’

‘I’ll drink to that,’ I said, though of course in my line of work bleeding hearts are the business.

Gerry had asked me a little while ago what I did for a living, and I’d told him export-import, then asked what he did. See, I slipped up once; I manufactured a career for myself only to find the guy I was drinking with was in the same line of work. Not good. These days I’m better, much cagier, and I don’t drink on the day of a hit. Not a drop. Not any more. Word was, I was slipping. Bullshit naturally, but sometimes rumours are difficult to throw off. It’s not as though I could put an ad in the newspapers. But I knew a few good clean hits would give the lie to this particular little slander.

Then again, today’s hit was no prize: it had been handed to me, a gift. I knew where she’d be and what she’d be doing. I didn’t just know what she looked like, I knew pretty well what she’d be wearing. I knew a whole lot about her. I wasn’t going to have to work for this one, but prospective future employers wouldn’t know that. All they’d see was the score sheet. Well, I’d take all the easy targets going.

‘So what do you buy and sell, Mark?’ Gerry asked.

I was Mark Wesley. I was English. Gerry was English too, but as international businessmen we spoke to one another in mid-Atlantic: the lingua franca of the deal. We were jealous of our American cousins, but would never admit it.

‘Whatever it takes, Gerry,’ I said.

‘I’m into that.’ Gerry toasted me with whisky. It was 3 p.m. local time. The whiskies were six quid a hit, not much more than my own soft drink. I’ve drunk in hotel bars all over the western world, and this one looked like all of them. Dimly lit even in daytime, the same bottles behind the polished bar, the same liveried barman pouring from them. I find the sameness comforting. I hate to go to a strange place, somewhere where you can’t find any focus, anything recognisable to grab on to. I hated Egypt: even the Coke signs were written in Arabic, and all the numerals were wrong, plus everyone was wearing the wrong clothes. I hate Third World countries; I won’t do hits there unless the money is particularly interesting. I like to be somewhere with clean hospitals and facilities, dry sheets on the bed, English-speaking smiles.

‘Well, Gerry,’ I said, ‘been nice talking to you.’

‘Same here, Mark.’ He opened his wallet and eased out a business card. ‘Here, just in case.’

I studied it. Gerald Flitch, Marketing Strategist. There was a company name, phone, fax and car-phone number, and an address in Liverpool. I put the card in my pocket, then patted my jacket.

‘Sorry, I can’t swap. No cards on me just now.’

‘That’s all right.’

‘But the drinks are on me.’

‘Well, I don’t know—’

‘My pleasure, Gerry.’ The barman handed me the bill, and I signed my name and room number. ‘After all,’ I said, ‘you never know when I might need a favour.’

Gerry nodded. ‘You need friends in business. A face you can trust.’

‘It’s true, Gerry, it’s all about trust in our game.’

Obviously, as you can see, I was in philosophical mood.

Back up in my room, I put out the Do Not Disturb sign, locked the door, and wedged a chair under the handle. The bed had already been made, the bathroom towels changed, but you couldn’t be too careful. A maid might look in anyway. There was never much of a pause between them knocking at your door and them unlocking it.

I took the suitcase from the bottom of the wardrobe and laid it on the bed, then checked the little Sellotape seal I’d left on it. The seal was still intact. I broke it with my thumbnail and unlocked the suitcase. I lifted out some shirts and T-shirts until I came to the dark blue raincoat. This I lifted out and laid on the bed. I then pulled on my kid-leather driving-gloves before going any further. With these on, I unfolded the coat. Inside, wrapped in polythene, was my rifle.

It’s impossible to be too careful, and no matter how careful you are you leave traces. I try to keep up with advances in forensic science, and I know all of us leave traces wherever we are: fibres, hairs, a fingerprint, a smear of grease from a finger or arm. These days, they can match you from the DNA in a single hair. That’s why the rifle was wrapped in polythene: it left fewer traces than cloth.

The gun was beautiful. I’d cleaned it carefully in Max’s workshop, then checked it for identifiers and other distinguishing marks. Max does a good job of taking off serial numbers, but I always like to be sure. I’d spent some time with the rifle, getting to know it, its weight and its few foibles. I’d practised over several days, making sure I got rid of all the spent bullets and cartridge cases, just so the gun couldn’t be traced back to them. Every gun leaves particular and unique marks on a bullet. I didn’t believe that at first either, but apparently it’s true.

The ammo was a problem. I didn’t really want to tamper with it. Each cartridge case carries a head stamp, which identifies it. I’d tried filing off the head stamps from a few cartridges, and they didn’t seem to make any difference to the accuracy of my shooting. But on the day, nothing could go wrong. So I asked Max and he said the bullets could be traced back to a consignment which had accompanied the British Army units to Kuwait during the Gulf War. (I didn’t ask how Max had got hold of them; probably the same source as the rifle itself.) See, some snipers like to make their own ammo. That way they know they can trust it. But I’m not skilled that way, and I don’t think it matters anyway. Max sometimes made up ammo for me, but his eyes weren’t so great these days.

The ammo was .338 Lapua Magnum. It was full metal-jacket: military stuff usually is, since it fulfils the Geneva Convention’s requirements for the most ‘humane’ type of bullet.

Well, I’m no animal, I wasn’t about to contravene the Geneva Convention.

Max had actually been able to offer a choice of weapons. That’s why I use him. He asks few questions and has excellent facilities. That he lives in the middle of nowhere is a bonus, since I can practise all day without disturbing anyone. Then there’s his daughter Belinda, who would be bonus enough in herself. I always take her a present if I’ve been away somewhere. Not that I’d... you know, not with Max about. He’s very protective of her, and she of him. They remind me of Beauty and the Beast. Bel’s got short fair hair, eyes slightly slanted like a cat’s, and a long straight nose. Her face looks like it’s been polished. Max on the other hand has been battling cancer for years. He’s lost about a quarter of his face, I suppose, and keeps his right side, from below the eye to just above the lips, covered with a white plastic prosthesis. Sometimes Bel calls him the Phantom of the Opera. He takes it from her. He wouldn’t take it from anyone else.

I think that’s why he’s always pleased to see me. It’s not just that I have cash on me and something I want, but he doesn’t see many people. Or rather, he doesn’t let many people see him. He spends all day in his workshop, cleaning, filing, and polishing his guns. And he spends a lot of his nights there, too.

Читать дальше