“I hate it when a critic pans me,” I said, “but I never killed one for it. I don’t know of any instance in the history of man where a critic got killed by his unhappy subject.”

“Maybe you don’t know your history,” she said coldly, looking away from me now, playing with the flowers again.

“Or history maybe got made here,” I said.

“Is that all? I’m a busy woman.”

“Ah yes. You have a weekend to run. Answer my question, and I’ll go.”

“What question?”

“I guess I never got around to asking it. Why did you and Gary break up?”

She sighed, straining for patience, looking at me with mock-pity and genuine condescension. “Gary was gay, Mr. Mallory.”

“Oh.”

“He didn’t know it, or didn’t admit it to himself, till college. He tried to be straight. Wanted to. We were friends... we tried to make something more of it. It just didn’t work out.”

“I see.”

“Now, if you’re quite through prying into my personal life, could I ask you to leave? I believe you have a role to play in just a few minutes...”

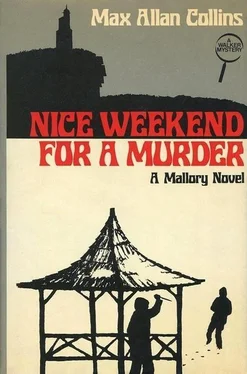

She was right; at eleven-thirty, to be exact. This was Saturday morning, which marked the second and final interrogation of suspects in The Case of the Curious Critic , just half an hour from now. I excused myself, and she wasn’t sorry to see me go. I went to the room, reported Mary Wright’s revelations to Jill, who said nothing, just mulled them over as she helped me get ready, as once again I nerded myself up to be Lester Denton — pencil mustache, Brylcreem, window-glass glasses, black-and-red-and-white-plaid corduroy suit and all.

But my heart was not in it, as I again sat in the little open parlor, with the cold frosted windows to my back and a roaring fireplace to my left, and a new batch of eager Mystery Weekenders all around, all but grilling me over that open fire.

The teams had divided their memberships up differently, so that no player would interrogate the same suspect twice — with one notable exception: Rick Fahy was again in the audience, in a front-row seat, in fact. Today he wore a green sweater and blue jeans, but his expression remained pained, and the gray eyes behind the thick glasses were still red-veined and dark-circled. He looked like hell.

Only today he didn’t ask a single question; his Hamilton Burger routine at yesterday’s interrogation — and the one conducted in earnest in last night’s encounter in the hall, for that matter — was conspicuously absent. He just sat staring at me with haunted eyes, unnerving me.

Jill was in the audience too, in the back, leaning against a support beam, getting her first look at Lester Denton in action.

Taking Jenny and Frank Logan’s places in the Overenthusiastic Yuppie Division were the fabled Arnolds, Millie and Carl. Millie — a slim little bubbly redheaded woman with attractive, angular features — was the interrogator, while her dark, mustached husband — a small man behind whose mild demeanor lurked a black belt in karate — sat taking the notes. They both wore ski sweaters and jeans, and sat forward, hanging on Lester’s every word.

“Are you aware that Sloth had published a vicious review of his own grandmother’s first mystery novel?” Millie said, her words rushing out. All of Millie’s words came rushing out.

“No,” I said. I was aware, however, that the grandmother role was being played by Cynthia Crystal.

“And that upon reading the review,” Millie continued, “she had a heart attack?”

“No,” I said. None of this was on my Suspect sheet; they were wasting their time going down this alley. But what the hell, it was their time.

Another player — a heavyset woman of about forty, dressed all in dark blue — gestured with her pen and said, “Sloth’s grandmother was seen going to his room shortly before you did. Did you see her?”

“No,” I said, meekly. “But I’m most relieved to hear the dear lady made a full recovery.”

“Then you weren’t aware,” Millie said, “that Sloth hired a thief to break into his grandmother’s house, to see if she’d changed her will, in the aftermath of that review?”

“No,” I said. All I knew of this aspect of Curt’s mystery was that Tim Culver was playing the thief.

Carl Arnold spoke; his deadpan expression barely cracked as he said, “Did Sloth say anything about his grandmother when you saw him?”

“No,” I said.

“He said nothing about a bribe?” Millie pressed.

“Well...”

“Did he say anything about a bribe? Specifically, that he told his grandmother he’d review her next book favorably, if she put him back in the will?”

“I knew nothing of that,” I said.

Another of the players, another Yuppie male in a white cardigan and pale blue shirt, picked up on my reaction to the word bribe and said, “You have a wealthy background, don’t you, Mr. Denton?”

“Well, I wouldn’t say ‘wealthy’...”

“What would you say?”

“Mother is well-fixed.”

“Did you offer money to Sloth that night?”

“Well, uh...”

“ Did you, Mr. Denton?”

Whereupon I broke down and confessed having attempted to bribe Roark K. Sloth; I further confessed to his having laughed off my “pathetic” attempt to do so.

Millie Arnold’s eyes were glittering; she smelled blood, and it put a great big smile right under her nose. “Did Sloth threaten you with a tape recording?”

“Y-yes,” Lester and I said. “He had recorded our entire conversation on a pocket machine.”

Soon the interrogation was over; I’d done an all right job — not as good as the first time around, but the first time around I had only a probable prank on my mind, not a real live murder. Still, a number of the interrogators hung around to compliment me and chat and laugh a little. They were having a great time, the players were; this was the best Mystery Weekend yet, several veterans said.

Among the lingerers were the Arnolds. Millie approached me and asked if she could give Lester a kiss; I said sure and she bussed Lester’s cheek.

“You were great ,” she said, slapping me on the shoulder. I wasn’t great. She was just enthusiastic.

Jill wandered up and I made introductions all around.

“You seemed pleased to get that piece of business about the tape,” I said to Millie and Carl, making polite conversation.

“Oh, yes — that helps us confirm a suspicion. Sloth tape-recorded everybody — Tom Sardini’s private-eye character has admitted to helping Sloth go so far as to wiretap.”

“Also,” Carl added, “Jack Flint’s character admitted to being threatened with a blackmail tape... but no tapes were found in Sloth’s room.”

“I see,” I said, not really giving a damn.

“Could I ask you a question?” Millie said, which was a question itself, actually.

“Sure,” I said.

“Did you send Jenny Logan around to check up on us? We figured she was trying to find out if we pulled that stunt outside your window. Because we brought our theatrical gear along and all.”

“Actually, I did ask her to check around.”

“Then you weren’t in on it?” Carl said.

“In on what?”

“The stunt,” Millie said. “We figured it was a part of the Mystery Weekend — something Curt Clark cooked up. Most of the teams are working it into their solutions.”

“Then they’re going down the wrong road,” I said. “The mystery is strictly limited to the information you gather from the interrogation sessions — nothing else before or after counts.”

“Then why,” Millie said, her constant smile momentarily disappearing into puzzlement, “would Rath have gone along with it?”

Читать дальше