“Boy,” he said.

“You said it,” Dominick said.

“Me too,” Nonaka said.

The bartender brought another round. The men sat drinking silently. Through the plate-glass window, Benny could see men in business suits coming out of the subway kiosk to wend their way homeward in the early evening hours, home to wife and loved ones, home to cooking smells, home to a weekend of fun and frivolity after five long days of hard work in offices hither and yon throughout Manhattan. For an insane but fleeting instant, Benny almost wished he was an honest citizen.

At seven o’clock that evening, Luther Patterson dialed Many Maples and asked to talk to Carmine Ganucci.

“Mr. Ganucci is not at home,” Nanny said. “He is in Italy.”

“Oh, the old Italy gag again, huh?” Luther said.

“Who is this?” Nanny asked.

“The kidnaper,” Luther said.

“This is not the kidnaper,” Nanny said.

“Are you trying to tell me what I am?” Luther said. “Madam...”

“I spoke to the kidnaper not two hours ago,” Nanny said.

“How could you have spoken to me two hours ago, when two hours ago I was sitting here...?”

“I was put in touch with the kidnaper two hours ago. A trusted friend put me in touch with the kidnaper. I have already arranged a meeting with him. I don’t know who this is...”

“ This is the goddamn kidnaper! ” Luther shouted frantically.

“No,” Nanny said.

“Madam, that other man is a fraud! Whoever’s representing himself to you as the kidnaper...”

“Good day, sir,” Nanny said, and hung up.

Luther looked at the mouthpiece. Angrily, he dialed the Larchmont number again, and waited until the phone rang on the other end.

“Many Maples,” Nanny said.

“Madam, I warn you...”

“If you don’t stop bothering me,” Nanny said, “I will notify the police.”

“Madam, you are playing a very dangerous game here. The life of an innocent child...”

There was a click on the line.

Luther replaced the receiver on its cradle. He rose from his desk and began pacing the room. He went back to the phone, lifted the receiver, put it back on its cradle again, lifted it yet another time, and then slammed it down viciously.

“What the hell is going on?” he shouted.

“Did you say something?” Ida called from the kitchen.

“Get that boy in here!” Luther shouted.

Luther pointed to a wing chair alongside the inoperative fireplace and said, “Sit.”

Lewis climbed into the chair, folded his hands in his lap, and looked across the room to where Luther peered at him from behind his desk. Ida stood in the doorway, drying her hands on her apron. Luther kept staring at the boy. In the kitchen, an electric clock hummed discreetly.

“My watch is missing,” Lewis said.

“Never mind your watch, I want to ask you some questions,” Luther said.

“It was on the dresser,” Lewis said.

“I said never mind the watch,” Luther said. “Let’s talk about your father.”

“He’s the one who gave me the watch,” Lewis said. “For my birthday.”

“I don’t care what he gave you,” Luther said. “I want to know where he is now.”

“Who?”

“Your father.”

“In Italy.”

“Then it’s true,” Luther said, and rolled his eyes toward the ceiling. “John, it’s really true. He’s in Italy.”

“Who’s John?” Lewis asked, looking up at the ceiling.

“Where in Italy?” Luther asked.

“Capri.”

“It’s true,” Luther mumbled. “Oh, God, it’s true.”

“Do you have a cleaning lady?” Lewis asked.

“What?”

“Because maybe she stole the watch.”

“Nobody stole your damn watch. Who’s in charge there?”

“Where?”

“In Larchmont. At your house. At Many Maples. While your father’s away.”

“Nanny.”

“Does she know your voice?”

“Sure. My voice? Sure, she does.”

“I want you to talk to her on the telephone.”

“What for?”

“Because she won’t believe me. I want you to talk to her, and tell her you’re alive and well, and that she’d better get the money right away because we’re not kidding around here. Do you understand me?”

“What money?” Lewis asked.

“The money to guarantee your safe return.”

“What if she doesn’t get the money?” Ida asked suddenly.

“She’ll get it, don’t worry,” Luther said.

“Answer me, Luther.”

“I have answered you.”

“You’re not planning on hurting him, are you?”

“I am planning on getting the money,” Luther said.

“Because if you touch him...”

“Please be quiet, Ida.”

“If you lay a hand on him...”

“Quiet, quiet.”

“I’ll kill you,” Ida said gently.

“Very nice,” Luther said. He looked toward the ceiling. “Nice talk for a wife, eh, Martin? Very nice talk.”

“I mean it,” Ida said.

“Nobody’s going to kill anybody,” Luther said. “We’re...”

“My father might,” Lewis said. “He knows a lot of tough guys.”

“Your father does not know any tough guys,” Luther said.

“Oh yes, he does.”

“Oh no, he does not. When I was your age, I thought my father knew a lot of tough guys, too, but he didn’t. They were merely his normal drinking companions. They only seemed tough because I was a bright, sensitive child who...”

“Well, these guys are tough,” Lewis protested. “I saw them.”

“I do not wish to waste any more time discussing fantasy as opposed to objective reality, do you understand?” Luther said.

“No.”

“I’m going to call your house now...”

“They are tough. They have guns and everything.”

“Um-huh,” Luther said, “guns and everything.” He went to the telephone. “When I get your governess on the line, I want you to come here immediately and talk to her.”

Lewis, offended, would not answer.

“Do you hear me?”

Sulking, Lewis nodded briefly.

“Good,” Luther said, and began dialing.

“Even the policemen were a little scared,” Lewis said.

“Mm-huh,” Luther said, and waited while the phone began ringing in Larchmont.

“When they came to the house,” Lewis said. “The policemen. Last year.”

“Yes, yes,” Luther said, and tapped his fingers impatiently on the desk.

“ All my father’s friends were there,” Lewis said,

“With their guns, no doubt,” Luther said.

“Yes, with their guns. And if you don’t believe me, it was in the Daily News .”

“Many Maples,” Nanny’s voice said on the other end of the line.

Luther’s mouth fell open. His eyes wide behind his glasses, he stared speechlessly at the boy across the room, whose last words — coupled with what his governess had just said into the telephone — now triggered belated recognition. Oh my God, Luther thought, oh my God.

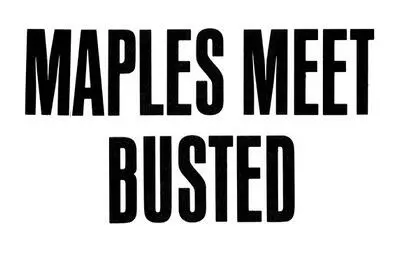

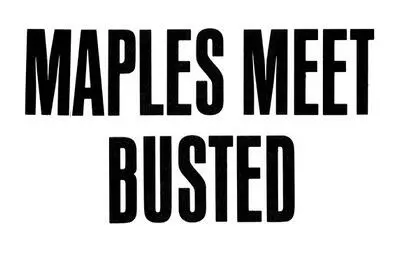

“Many Maples,” Nanny said again, as though diabolically reiterating the name, and forcing Luther to recall in startlingly vivid black-and-white the two headlines that had paraded across the top of two separate stories in two separate newspapers not eleven months ago. The first headline was printed in the bold type favored by the city’s morning tabloid, and it read:

The second headline was printed in the more restrained type preferred by the city’s other morning paper, and it read:

Читать дальше