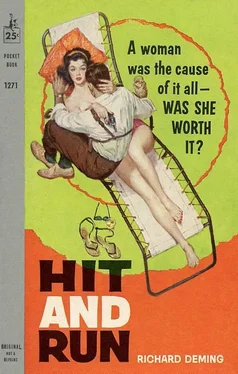

He scooped her into his arms.

When the second body was safely locked in the trunk, Calhoun returned to the house to tidy up. First he carefully wiped off the gun and dropped it into a pocket. Then he went through the house wiping every surface he could recall touching. He considered digging out the bullet buried in the wall, then decided against it. Helena’s disappearance was going to mystify the police anyway, and one more mystery wouldn’t matter.

He turned off all the lights and left the keys on the kitchen table. He was about to pull the back door closed when he remembered something Helena had said. Lawrence Powers’ clothing was still in the garage.

Re-entering the kitchen, he recovered the keys and crossed the back lawn to the garage. Unlocking it, he opened one garage door only far enough to slip inside. He slid it shut again behind him and used his lighter to locate the garage’s light switch.

A tool bench running the length of the back wall seemed the most likely place of concealment. Calhoun pulled open drawers containing nails and screws, electrical fittings, and odds and ends. None of the drawers contained any clothing.

He searched the three cars in the garage with equal lack of result. Then he frowningly ran his gaze over the empty rafters and bare walls. Wherever Helena had hidden the clothing, she had done an excellent job, he decided. For there was nowhere else to look.

Giving up, he switched off the light, relocked the garage, and returned the keys to the kitchen table. The house’s back door clicked shut with a sound of finality when he pulled it closed from outside.

He got into the Plymouth and drove home.

When he had parked in front of his flat, he sat in the car thinking. His initial plan had been to leave Helena’s body in the car trunk until he was ready to dispose of it. But it occurred to him that with the hot sunny days Buffalo was having, the sun’s beating down on the car all the next day would have an unfortunate effect on the body. And it would have to stay there until after dark the next night. There were arrangements to be made before he could get rid of the bodies, and the arrangements couldn’t be made until morning.

Also, he didn’t relish driving around the next day with a dead body in the car trunk. He decided it would be much safer in his flat.

He got it inside in the same manner that he had carried Cushman in. He laid it on the front-room floor next to the other.

Outside again, he closed and locked the trunk, considered, and then pulled the spare tire from the rear seat. He decided that the best way to begin the next night’s operation was to stow Cushman’s body in the car trunk and Helena’s on the back floor with a blanket over it. The spare would be in the way.

He rolled the wheel up to the door of his flat, then carried it inside. He left it leaning against the kitchen wall.

Then, one at a time, he carried the two bodies into the bedroom and laid them side by side on his bed. Rigor mortis was beginning to set in on Cushman, but Calhoun didn’t bother to straighten the limbs. From his police experience he knew that rigor mortis would pass within twenty-four hours, and while the bodies wouldn’t be exactly limp, the residual stiffness wouldn’t prevent him from bending the joints sufficiently to fit both bodies into the car.

He opened the bedroom window slightly from the top to allow ventilation, then switched off the bedroom light and went into the front room, pulling the door closed behind him.

He sat in the front room smoking and thinking. His plan of body disposal was basically the same one he had used for Lawrence Powers. He knew a stretch of deserted beach only a mile from a boat livery at Sheridan Bay. He could park his car there and walk the mile to the livery. Knowing the shoreline in this area, he was sure he could find the beach without a signal from shore.

In the morning he would drive up Main Street to the large Sears, Roebuck branch there and buy some sash cord and four small-boat anchors. By this time tomorrow night, he told himself, there would be no evidence of either murder.

He slept on the couch in the front room.

By noon the next day Calhoun had completed all necessary arrangements. In the spare-tire channel in the car trunk there were twenty-four feet of sash cord and four eight-pound small-boat anchors. He had made arrangements with the boat livery at Sheridan Bay to rent a boat at eight P.M. and keep it until midnight.

Because it would have to be completely dark when he loaded the bodies in the car, his procedure was going to differ from the one he had used in Cleveland. This time he planned to take the boat out before dark and beach it at the deserted strip of beach where his car was parked. He’d then drive back to town for the bodies and bring them back to the beached boat.

On the way back from Sheridan Bay, Calhoun stopped for some lunch. He got home about one P.M.

He was just taking the key to his flat from his pocket when two men got out from a car parked at the curb and moved toward him. Glancing over his shoulder, he recognized them and a chill went along his spine. One, a thin, mournful-looking man with a pinched face and deeply sunken cheekbones, was Sergeant Gerald Budding. The other, a stocky, round-faced man with a perpetual smile was his partner, Officer Henry Gent.

Calhoun dropped his key back in his pocket and waited.

“Afternoon, Barney,” Sergeant Budding said when they came to a stop at the bottom step.

“How are you, Gerry?” Calhoun said. “Hello, Hank.”

“Hi,” Henry Gent said with a cheerful smile. “Hot, isn’t it?”

“Uh huh.”

Sergeant Budding said, “Been waiting for you to come home, Barney. Can we come in and talk a minute?”

Calhoun thought of the two bodies stretched out on his bed. “Pretty hot indoors,” he said. “Let’s make it out here.” He sat on the top step and lit a cigarette with hands he barely managed to keep from trembling.

“Okay,” the mournful-looking Budding said. “Want to ask a few questions about Lawrence Powers, Barney.”

For the space of a second Calhoun’s heart stopped. Then he said calmly, “The banker who’s disappeared? I saw it in the paper. Sounded like a voluntary skip, the way it was written up. What’s Homicide’s interest in it? You boys are still with Homicide and Arson, aren’t you?”

“Yeah,” Budding said. “We thought it was a voluntary skip at first, too. Now we think it was a homicide.”

“No fooling?” Calhoun asked. “How do you figure?”

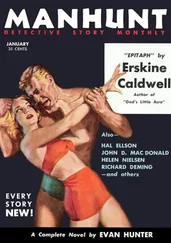

“We really fell into it by accident,” Budding told him. “Some crank phoned in an anonymous tip that Powers’ wife was the hit-and-runner who killed some old man a couple of weeks back. Couple of guys from the Hit-and-Run squad made a routine check, and her car checked out clear. But there’s always a chance on a thing like that that the suspect got some shady repairman to fix up the damage, you know. The boys shook down her garage on the off-chance they’d find some damaged part of the car that had been replaced. They didn’t find any damaged part, but they found some men’s clothing in a workbench drawer.”

Calhoun’s heart stopped again, then resumed pounding at an increased rate. “What kind of clothing?” he asked with forced interest.

“A brown suit, brown shoes, socks, underwear, shirt, and tie. The works. Plus a tie clip, wrist watch, and a wallet with money in it and papers showing it belonged to Lawrence Powers.”

The idiot , Calhoun thought, meaning Helena. After all his careful planning, she had had to leave a glaring loose end like this.

He said, “How do you know he didn’t leave the clothes there himself? Be logical to dump identification papers and personal items, wouldn’t it, if he wanted to disappear and establish a new identity somewhere?”

Читать дальше