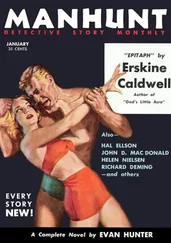

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen,” the young man said. “Welcome to the White Swan. It’s time once again for the White Swan’s nightly show.”

“Oh, we’re going to have a floor show,” Helena said in a pleased voice.

The young M.C. told a couple of off-color jokes, which brought raucous laughter from some of the audience but didn’t stir Helena from her normal expressionlessness. She didn’t look offended, but she didn’t look amused, either. If anything, she looked bored.

Having warmed up the audience to the limit of his limited capabilities, the M.C. proceeded to eulogize the coming attractions of the evening. His announcements that they would be entertained by a female vocalist (“that great young lady with the great big voice”) and a tap dancer (“a great young man”) were greeted by total silence. But when he mentioned “our featured dancer, that great young performer, Ann Devoe,” he brought down the house. There were wild hand-clapping, whistles, and catcalls.

Helena said, “She must be good. Did you ever hear of her before?”

“The audience reaction is familiar,” Calhoun said dryly. “I imagine I’ve seen the same act. The applause doesn’t necessarily mean she’s good.”

Helena asked, “What do you mean?”

“It’s probably a strip act.”

“Oh,” Helena said with interest. “I’ve never seen one.”

The young M.C. finally retired, and the great young lady with the great big voice came on. She was a buxom woman in her mid-thirties, and the M.C. had been right in describing her voice. It shook the building. Unfortunately, volume was its sole attribute. Nevertheless she received applause, not for her talent but for her lyrics. She sang two songs, both of them the double-meaning sort of thing you usually hear only at stag parties.

Calhoun studied Helena with interest while the woman sang. Helena’s face was totally blank, and she was watching the vocalist with the intent gaze of an entomologist peering through a microscope at a new type of insect life.

When the woman finished her act, Calhoun said, “Penny for your thoughts.”

Helena glanced at him. “I was just wondering what could bring a woman to make that kind of vulgar display in public.”

“The necessity of making a living,” he said dryly. “She’s probably an ex-stripper with too much sag for the bump-and-grind circuit. You must have lived a very sheltered life.”

“Why do you say that?”

“You’ve never seen a strip act. Apparently you never heard a dirty song before. And from your expression when the M.C. was on, you never before heard a dirty joke told out loud.”

Helena said reflectively, “Perhaps I have been sheltered. Lawrence would never think of taking me to a place like this. And if we got into one by accident, as we did tonight, he’d drag me out before the show started.”

“Doesn’t your friend Cushman ever take you to night clubs?”

She shook her head. “We stick to quiet places. You have to when you’re practicing adultery.”

The casual manner in which she referred to her own sins intrigued Calhoun, particularly after her comment about the vocalist. He decided that it was probably only public vulgarity she disapproved of, and that otherwise she was quite matter-of-factly amoral. A moment later he became sure of it.

He said, “Weren’t you ever exposed to life before your marriage?”

“I was married at eighteen,” she told him. “I was a clerk in Lawrence’s bank after I graduated from high school, and we were married when I’d been there only two months. Lawrence was thirty-eight at the time. He’s always been rather protective. Our relationship has been more of a father-daughter one than a husband-wife one. Which may be the reason I take lovers.”

“Lovers?” he asked. “There’ve been more than just Cushman?”

“In twelve years of marriage?” she said with raised eyebrows. “Of course.” She gave the hint of a smile. “Lawrence thinks I’m frigid.”

Her frankness both startled him and puzzled him. From another woman, he would have diagnosed the conversation as a bald invitation to become her lover. But Helena was an almost complete enigma to him. He suspected her casualness about her love life was not assumed to impress him but was her actual attitude. She was frank about her adulteries because they were unimportant to her.

Remembering the time he had kissed her, and her total lack of response, he wondered if her husband was right and if perhaps she was frigid.

The tap dancer came on, went through a routine act, and was rewarded with tepid applause. Then the feature act came on.

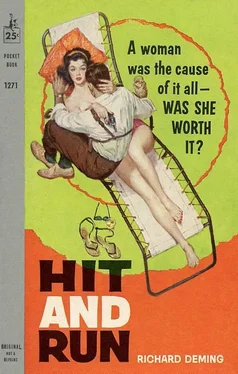

Ann Devoe was a voluptuous redhead in her early twenties. She had rather plain features, but a smooth, well-formed body and remarkably large breasts with no trace of sag. She did what is known in the trade as a street strip, which is the taking off of ordinary street clothes instead of a trick gown with numerous zippers that allow it to be removed a section at a time.

She started in a conservative skirt, jacket, and blouse, nylon stockings and plain pumps, and ended in nothing. In a way it was more provocative than the ordinary strip act, for she managed to create the illusion that she wasn’t a professional performer giving a professional performance, but merely an attractive young woman disrobing in public. She heightened the impression by seeming to be unaware of the audience. She maintained a deadpan expression the entire time, and she eliminated the usual gliding motions of the strip dance. She merely stood there with a thoughtful expression on her face and slowly disrobed, looking for all the world like a young secretary getting ready to take a shower and go to bed. When she was completely nude, she stood motionless for a few seconds, then made one slow, complete turn and walked off the floor.

The applause was deafening, but she didn’t come back for any bows.

Calhoun said, “What’s your verdict on that?”

“She has a lovely figure.”

“I mean, do you wonder how she can bring herself to do it?”

Helena looked at him. “It’s not the same as the vulgar songs. I could do that if I needed the money.”

When he looked surprised, she said, “I’m not ashamed of my body.”

The remark made him recall the day he had surprised her sun bathing. She had certainly exhibited no embarrassment then. He had a mental picture of her performing the act they had just seen, and decided she probably could do it without vulgarity. With her cool, unemotional manner, she would make it a display of beauty rather than a display of sex.

He wondered again if she were frigid. He also wondered if he would ever understand her.

After the floor show they had another drink and then decided to dance despite the orchestra’s lack of talent. Calhoun discovered she was a remarkably good dancer.

They stayed at the White Swan until closing time, alternately dancing and drinking. And with each drink and with each chance to hold her in his arms, Calhoun’s temperature rose another degree.

He began to get the impression that the closeness of their bodies on the dance floor was having an effect on her, too. Not from anything she said, for the conversation didn’t touch on love or morals again. But each time they danced she seemed to move more compliantly into his arms and her eyes seemed to get a warmer shine.

When he finally drove the Dodge back into the carport, he was on the verge of suggesting she come into his cabin for a nightcap, with the idea that more interesting things might develop. But before he could open his mouth, Helena jumped out of the car and went to her cabin through the carport door without saying a word to him.

Then as he sat there foolishly looking at her closed door, he experienced a terrific letdown. He was tempted to get angry, but reflected that she hadn’t actually said or done anything to make him think she had been sharing his cozy thoughts. Perhaps she had just now realized the direction his thoughts were taking, and wanted to leave no doubts in his mind that their relationship was strictly a business one.

Читать дальше