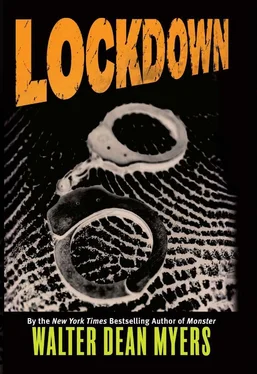

Walter Myers - Lockdown

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Walter Myers - Lockdown» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Криминальный детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Lockdown

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lockdown: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Lockdown»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Lockdown — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Lockdown», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

A woman down the hall had died, and Simi had to clean out and disinfect the room. She said that was the policy. She said Mr. Hooft could wait if I wanted to help her.

We scrubbed every bit of the room with a brush and disinfectant, which she poured into the hot water. It stunk something terrible, and once or twice I thought I was going to throw up. We scrubbed and washed until eleven o'clock and then opened all the windows to let the room air out.

When I got to Mr. Hooft's room, he was mad.

"So you come anytime you want to now?" he said, looking away from me.

"You missed me, man?" I asked him. "I was helping Simi clean the room down the hall."

"If the Japanese had captured you, they would have killed you right away," he said. "They called us all criminals, but with you, they would have been right!"

"You know what I was wondering?" I sat in the corner chair. "I saw some pictures of people in a German prison camp and they were skinny as anything. What did you get to eat?"

He looked over at me for a second, then away. Then he must have remembered something, because he gave a little jump and started laughing.

"You know what rijsttafel is?" he asked.

"No."

"It's a big bowl of rice with lots of side dishes. You can have curried meats, or vegetables, sweet or not sweet, soups, whatever you want," Mr. Hooft said. "But when the Japanese had us, they gave us strontstafel, little brown balls of rice mixed with cabbage. It was awful. We were always hungry, but no one died of hunger among the children or the women. Some of the men died from being worked so hard, and some died from the beatings or if they got sick. Some just gave up."

"It must have been rough," I said.

"Life is rough," Mr. Hooft said. "You didn't know that?"

"I thought you had it easy after you got out, the way you were talking and everything, but you just made some of that up, right?"

"Everything in life is made up," Mr. Hooft said. "You make up that you are happy. You make up that you are sad. You make up that you are in love. If you don't make up your own life, who's going to make it up for you? It's bad enough when you die and everybody can make up their own stories about you."

The doctor came in with Nancy Opara. He asked Mr. Hooft how he was doing.

"Why, do you need somebody to practice medicine on?" Mr. Hooft asked. "Maybe you have an extra needle you need to stick somewhere."

"Don't be so mean, old man!" Nancy said. "The doctor just has to check you out."

"I would rather be mean than be an African!" Mr. Hooft said.

"Yes, darling." Nancy started to close the door, then pointed at me and motioned for me to leave.

"Come back later, Reese, and help me count my fingers and toes so these thieves can't get them," Mr. Hooft said. "You're the only one I can trust in here."

"Yes, sir."

Simi was in the hallway and asked if I wanted to go to the cafeteria. I said yes, and we went up and she bought two orange sodas. She'd started to tell me about her grandson when her pager went off.

"My husband. I know what he wants. He works in a restaurant in New Rochelle and he's going to try to convince me that whatever they're having there on special he should bring home for us to eat tonight. What a cheap man. I'm going to go get my cell phone and call him."

Simi left, and I watched as two women in wheelchairs came off the elevator and rolled up to the counter.

Sitting alone in the cafeteria, watching some of the residents getting their lunch on the far side of the room, I felt a sadness come over me. It was like a window had opened and a bad wind was pouring in from the outside. This was what I wanted, to be alone and not having someone watching me or locking a door behind me or cuffing me to a wall. I didn't want to have to fight anyone or watch my back every minute of the day. But that wasn't what my life had become. I wanted to be alone, but everyone I came into contact with had something over me, able to put me in detention or in juvy for more years.

My mind went back to the call from the detectives. I wondered if they were going to come pick me up this evening. I imagined them in their car driving along the highway, talking about what they did over the weekend, listening to the news. I knew I hadn't done what they were saying, but it really didn't matter. Some girl had died and they were making sure that somebody was going to pay for her death.

On the street, before I got arrested, I was Maurice Anderson. I wasn't living no big-time life, but I was me. Now I wasn't me but what I had done. The rules were different for a felon.

Three years or twenty years, the detective had said. What kind of choice was that? Just thinking about twenty years was like dying. Mr. Pugh had once said that I should get down on my knees and thank God I was in a juvenile facility.

"This is paradise," he had said.

It wasn't no paradise. There were rolls of barbed wire along the fences, doors that slammed shut behind you, and doors that were locked in front of you. And guards. I imagined them going home every day to their families. Maybe they talked about Progress. Maybe they just showered and tried to get the stink of us off their bodies. I don't know.

Twenty years had to be dying, had to be hell. Being in a prison with grown men, with gangs, and knowing that the whole world thought you were garbage.

Three years was the good thing they were offering. All I had to do was say yes and move my head away from going home. Just stop looking out the window wishing I could take a walk without thinking about where I was going and start thinking about how I was going to manage to keep myself in one piece for three more years.

Crying wanted to come. In a way it was like Reese was dead and it was me, whoever I was, whatever I was, grieving over him. Maybe I should get a tattoo, R.I.P. on my chest, so whenever I looked in the mirror I could see it.

I started thinking about my case again. When I first got arrested, I thought maybe I would walk. Then I saw the list of charges and I thought it was a joke. Nobody was laughing. If Freddy and his people all testified that I gave him drugs, I was dead meat.

And what I didn't want to think about, the thing that was like chewing on my insides, was what I would do if I did get out. They'd probably put me in some wack school where you didn't learn nothing and just sat in class all day wondering where you were going to get some pocket money. They said that most of the people from 'round my way who go to jail once, go back again. Maybe even when they were out, there wasn't nothing there for them but a road back.

"Everything in life is made up," Mr. Hooft had said.

I wanted to make up a life. I could imagine myself walking down the street holding my head up high like I wasn't concerned about anything. I tried dreaming up a nine-to-five deal making maybe six or seven hundred bucks a week. But every time I started imagining what I might be doing, the detective's voice kept coming through.

"We'll be up there Monday to bring you back to the city," he had said.

I thought I could get up and just walk down the stairs and out into the street. What would happen? Someone would miss me and the police would start looking for me. Where would I go? What would I do?

Tired. Tired and sad. It was better to get mad at somebody and fight than just to feel so tired and sad all the time. The idea came to me, came like I should have known it all the time, that tired and sad was how I always felt. I knew I had to get to someplace else, someplace where I wasn't tired and I wasn't beat down and sad.

Miss Rossetti and people like her didn't seem sad, but they didn't have my life, not knowing what was going down next or what was going to be shaking when you went home, or the mirrors where you look in them and don't see nothing you like.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Lockdown»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Lockdown» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Lockdown» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.