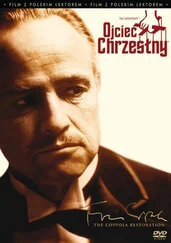

The Godfather

by Mario Puzo

Behind every great fortune there is a crime.

Balzac

Amerigo Bonasera sat in New York Criminal Court Number 3 and waited for justice; vengeance on the men who had so cruelly hurt his daughter, who had tried to dishonor her.

The judge, a formidably heavy-featured man, rolled up the sleeves of his black robe as if to physically chastise the two young men standing before the bench. His face was cold with majestic contempt. But there was something false in all this that Amerigo Bonasera sensed but did not yet understand.

“You acted like the worst kind of degenerates,” the judge said harshly. Yes, yes, thought Amerigo Bonasera. Animals. Animals. The two young men, glossy hair crew cut, scrubbed clean-cut faces composed into humble contrition, bowed their heads in submission.

The judge went on. “You acted like wild beasts in a jungle and you are fortunate you did not sexually molest that poor girl or I’d put you behind bars for twenty years.” The judge paused, his eyes beneath impressively thick brows flickered slyly toward the sallow-faced Amerigo Bonasera, then lowered to a stack of probation reports before him. He frowned and shrugged as if convinced against his own natural desire. He spoke again.

“But because of your youth, your clean records, because of your fine families, and because the law in its majesty does not seek vengeance, I hereby sentence you to three years’ confinement to the penitentiary. Sentence to be suspended.”

Only forty years of professional mourning kept the overwhelming frustration and hatred from showing on Amerigo Bonasera’s face. His beautiful young daughter was still in the hospital with her broken jaw wired together; and now these two animales went free? It had all been a farce. He watched the happy parents cluster around their darling sons. Oh, they were all happy now, they were smiling now.

The black bile, sourly bitter, rose in Bonasera’s throat, overflowed through tightly clenched teeth. He used his white linen pocket handkerchief and held it against his lips. He was standing so when the two young men strode freely up the aisle, confident and cool-eyed, smiling, not giving him so much as a glance. He let them pass without saying a word, pressing the fresh linen against his mouth.

The parents of the animales were coming by now, two men and two women his age but more American in their dress. They glanced at him, shamefaced, yet in their eyes was an odd, triumphant defiance.

Out of control, Bonasera leaned forward toward the aisle and shouted hoarsely, “You will weep as I have wept— I will make you weep as your children make me weep”— the linen at his eyes now. The defense attorneys bringing up the rear swept their clients forward in a tight little band, enveloping the two young men, who had started back down the aisle as if to protect their parents. A huge bailiff moved quickly to block the row in which Bonasera stood. But it was not necessary.

All his years in America, Amerigo Bonasera had trusted in law and order. And he had prospered thereby. Now, though his brain smoked with hatred, though wild visions of buying a gun and killing the two young men jangled the very bones of his skull, Bonasera turned to his still uncomprehending wife and explained to her, “They have made fools of us.” He paused and then made his decision, no longer fearing the cost. “For justice we must go on our knees to Don Corleone.”

* * *

In a garishly decorated Los Angeles hotel suite, Johnny Fontane was as jealously drunk as any ordinary husband. Sprawled on a red couch, he drank straight from the bottle of scotch in his hand, then washed the taste away by dunking his mouth in a crystal bucket of ice cubes and water. It was four in the morning and he was spinning drunken fantasies of murdering his trampy wife when she got home. If she ever did come home. It was too late to call his first wife and ask about the kids and he felt funny about calling any of his friends now that his career was plunging downhill. There had been a time when they would have been delighted, flattered by his calling them at four in the morning but now he bored them. He could even smile a little to himself as he thought that on the way up Johnny Fontane’s troubles had fascinated some of the greatest female stars in America.

Gulping at his bottle of scotch, he heard finally his wife’s key in the door, but he kept drinking until she walked into the room and stood before him. She was to him so very beautiful, the angelic face, soulful violet eyes, the delicately fragile but perfectly formed body. On the screen her beauty was magnified, spiritualized. A hundred million men all over the world were in love with the face of Margot Ashton. And paid to see it on the screen.

“Where the hell were you?” Johnny Fontane asked.

“Out fucking,” she said.

She had misjudged his drunkenness. He sprang over the cocktail table and grabbed her by the throat. But close up to that magical face, the lovely violet eyes, he lost his anger and became helpless again. She made the mistake of smiling mockingly, saw his fist draw back. She screamed, “Johnny, not in the face, I’m making a picture.”

She was laughing. He punched her in the stomach and she fell to the floor. He fell on top of her. He could smell her fragrant breath as she gasped for air. He punched her on the arms and on the thigh muscles of her silky tanned legs. He beat her as he had beaten snotty smaller kids long ago when he had been a tough teenager in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen. A painful punishment that would leave no lasting disfigurement of loosened teeth or broken nose.

But he was not hitting her hard enough. He couldn’t. And she was giggling at him. Spread-eagled on the floor, her brocaded gown hitched up above her thighs, she taunted him between giggles. “Come on, stick it in. Stick it in, Johnny, that’s what you really want.”

Johnny Fontane got up. He hated the woman on the floor but her beauty was a magic shield. Margot rolled away, and in a dancer’s spring was on her feet facing him. She went into a childish mocking dance and chanted, “Johnny never hurt me, Johnny never hurt me.” Then almost sadly with grave beauty she said, “You poor silly bastard, giving me cramps like a kid. Ah, Johnny, you always will be a dumb romantic guinea, you even make love like a kid. You still think screwing is really like those dopey songs you used to sing.” She shook her head and said, “Poor Johnny. Goodbye, Johnny.” She walked into the bedroom and he heard her turn the key in the lock.

Johnny sat on the floor with his face in his hands. The sick, humiliating despair overwhelmed him. And then the gutter toughness that had helped him survive the jungle of Hollywood made him pick up the phone and call for a car to take him to the airport. There was one person who could save him. He would go back to New York. He would go back to the one man with the power, the wisdom he needed and a love he still trusted. His Godfather Corleone.

* * *

The baker, Nazorine, pudgy and crusty as his great Italian loaves, still dusty with flour, scowled at his wife, his nubile daughter, Katherine, and his baker’s helper, Enzo. Enzo had changed into his prisoner-of-war uniform with its green-lettered armband and was terrified that this scene would make him late reporting back to Governor’s Island. One of the many thousands of Italian Army prisoners paroled daily to work in the American economy, he lived in constant fear of that parole being revoked. And so the little comedy being played now was, for him, a serious business.

Читать дальше