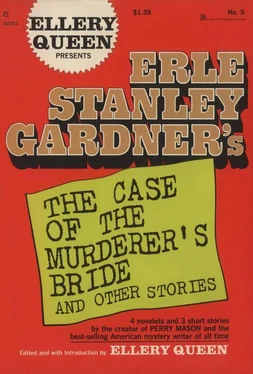

Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Dr. Dixon laughed. “She may have been a wallflower when Ives married her, but she has turned into an orchid now. With a face and figure like hers it won’t be long before a string of eligible males will be trying to make her forget the tragedy that made her a wealthy widow.”

“Wealthy?” Cortland repeated, and his eyebrows raised.

Dr. Dixon nodded. “Mrs. Ives mentioned that she and her husband had joint insurance policies and joint bank accounts — all payable to the survivor. It was her idea, not that she ever thought of personal gain. She wanted them for the protection of their future children.”

Dr. Dixon shook his head. “She seems to have outwitted him all around. But what puzzles me is how Ives happened to grab the wrong life preserver. Evidently, he put detergent in only one cushion. How the devil did he make the mistake?”

He frowned suddenly. “Do you suppose she could have switched the cushions?”

Cortland shook his head. “I did,” he admitted. “When we were down looking over the boat last night.”

Dr. Dixon stared at him. “Do you mean to say you knew what Ives had in mind?”

“Hell, no,” Cortland confessed. “I just swapped those cushions around as a matter of principle. Just good old police routine. I knew we were dealing with a crook and I acted automatically. It is an axiom of police procedure — never let a crook leave a setup!”

Only by Running (Flight into Disaster)

Only once before had the woman in the club car ever known panic — not merely fear but the real panic which paralyzes the senses.

That had been in the mountains when she had tried to take a short cut to camp. When she realized she was lost there was a sudden overpowering desire to run. What was left of her sanity warned her, but panic made her feel that only by flight could she escape the menace of the unknown. The silent mountains, the somber woods, had suddenly become enemies, leering in hostility. Only by running did she feel she could escape — by running — the very worst thing she could have done.

Now, surrounded by the luxury of a crack transcontinental train, she again experienced that same panic. Once more there was that overpowering desire to run.

Someone had searched her compartment while she had been at dinner. She knew it was a man. He had tried to leave things just as he had found them, but there were little things that a woman would have noticed that the man didn’t even see. Her plaid coat, which had been hung in the little steel closet so that the back was to the door, had been turned so the buttons were toward the door. A little thing, but a significant thing which had been the first to catch her attention, leaving her, for the moment, cold and numb.

Now, seated in the club car, she strove to maintain an attitude of outward calm by critically inspecting her hands. Actually, she was taking stock of the men in the car.

Her problem was complicated by the fact that she was a compactly formed young woman, with smooth lines, clear eyes, a complete quota of curves, and, under ordinary circumstances, a smile always quivering at the comers of her mouth. It was, therefore, only natural that every male animal in the club car sat up and took notice.

The fat man across the aisle who held a magazine in his pudgy hands was not reading. He sat like a Buddha, motionless, his half-closed, lazy-lidded eyes fixed on some imaginary horizon far beyond the confines of the car; yet she felt those eyes were taking a surreptitious interest in everything she did. There was something sinister about him, from the big diamond on the middle finger of his right hand to the rather ornate twenty-five-dollar tie which begged for attention above the bulging expanse of his vest.

Then there was the man in the chair on her right. He hadn’t spoken to her but she knew that he was going to, waiting only for an opportunity to make his remark sound like the casual comment of a fellow passenger. He was in his late twenties, bronzed by exposure, steely-blue of eye. His mouth held the firmness of a man who has learned to command himself first and then others.

The train lurched. The man’s hand reached for the glass on the little stand between them. He glanced apprehensively at her skirt.

“Sorry,” he said.

“It didn’t spill,” she replied.

“I’ll lower the danger point,” he said, raising the glass to his lips. “Going all the way through? I’m getting off at six o’clock in a cold Wyoming morning.”

For a moment her panic-numbed brain failed to appreciate the full significance of his remark, then she experienced a sudden surge of relief. Here, then, was one man whom she could trust. She knew that the man who had searched her baggage hadn’t found what he wanted because she had it with her, neatly folded, fastened to the bottom of her left foot by strong adhesive tape.

Therefore the enemy would stay on the train as long as she was on it, waiting, watching, growing more and more desperate, until at last, perhaps in the dead of night, he would... She knew only too well that the enemy would stop at nothing. One murder had already been committed.

But now she had found one person whom she could trust, a man who had no interest in the thing she was hiding, a man who might well be a possible protector.

He seemed mildly surprised at her sudden friendliness.

“I didn’t know this train stopped anywhere at that ungodly hour,” she ventured, smiling.

“A flag stop,” he explained.

Across the aisle the fat man had not moved a muscle, yet she felt absolutely certain that those glittering eyes were concentrating on her and that he was listening as well as watching.

“You live in Wyoming?” she asked.

“I did as a boy. Now I’m going back. I lived and worked on my uncle’s cattle ranch. He died and left it to me. At first I thought I’d sell it. It would bring a fortune. But now I’m tired of the big cities, so I’m going back to live on the ranch.”

“Won’t it be frightfully lonely?”

“At times.”

She wanted to cling to him now, dreading the time when she would have to go back to her compartment and be alone.

She thought the trainmen must have a master key which could open even a bolted door — in the event of sickness, or if a passenger rang for help. There must be a master key which would manipulate even a bolted door. And if trainmen had such a key, the man who had searched her compartment could have one.

Frank Hardwick, before he died, had warned her. “Remember,” he had said, “they’re everywhere. They’re watching you when you don’t know you’re being watched. When you think you’re running away and into safety, you’ll simply be rushing into a carefully laid trap.”

She hoped there was no trace of the inner tension as she smiled at the man on her right. “Do tell me about the cattle business,” she said brightly...

All night she had crouched in her compartment, watching the door, waiting for the first flicker of telltale motion which would show the doorknob being turned. Then she would scream, pound on the walls of the compartment, make a commotion.

Nothing had happened.

Probably that was the way “they” had planned it. They’d let her spend one sleepless night, then when fatigue had numbed her senses...

The train abruptly slowed. She glanced at her wrist watch, saw that it was 5:55, and knew the train was stopping for the man who had inherited the cattle ranch. Howard Kane was the name he had given her after she had encouraged him to tell her all about himself. Howard Kane, 28, unmarried, presumably wealthy, his mind scarred by battle experiences, seeking the healing quality of the big silent places.

There was a quiet competency about him; one felt he could handle any situation — and now he was getting off the train.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.