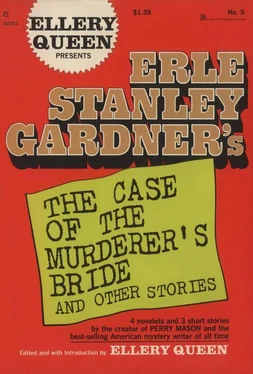

Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Rubber-glove Giffen laughed at his little joke.

“I said to hell with you,” George Ollie said.

Larry Giffen’s fist clenched. “I guess you need a damn good working over, Georgie boy. You shouldn’t be disrespectful.”

Stella’s voice cut in. “Leave him alone. I said you’d get the money. George doesn’t want the electric chair.”

Larry turned back to her. “I like ’em sensible, sweetheart. Later on I’ll tell you about it. Right now it’s all business. Business before pleasure. Let’s go.”

“Ninety-seven four times to the right,” Stella said.

“Well, well, well,” Giffen observed. “She knows the combination. We both know what that means, Georgie boy, don’t we?”

George, his face red and swollen from the impact of the slaps, stood helpless.

“It means she really is part of the place,” Giffen said. “I’ve got a half interest in you too, girlie. I’m looking forward to collecting on that too. Now what’s the rest of the combination?”

Giffen bent over the safe; then, suddenly thinking better of it, he straightened, slipped the snub-nosed revolver into his left hand, and said, “Just so you don’t get ideas, Georgie boy — but you wouldn’t. You don’t like the idea of the hot squat, do you?”

Stella, white-faced and tense, called out the numbers. Larry Giffen spun the dials on the safe, swung the door open, opened the cash box.

“Well, well, well,” he said, sweeping the bills and money into his pocket. “It was a good day, wasn’t it?”

Stella said, “There’s a hundred-dollar bill in the ledger.”

Big Larry pulled out the ledger. “So there is, so there is,” he said, surveying the hundred-dollar bill with the slightly tom comer. “Girlie, you’re a big help. I’m glad you go with the place. I think we’re going to get along swell.”

Larry straightened, backed away from the safe, stood looking at George Ollie.

“Don’t look like that, Georgie boy. It isn’t so bad. I’ll leave you enough profit to keep you in business and keep you interested in the work. I’ll just take off the cream. I’ll drop in to see you from time to time, and, of course, Georgie boy, you won’t tell anybody that you’ve seen me. Even if you did, it wouldn’t do any good because I came out the front door, Georgie boy. I’m smart. I’m not like you. I don’t have something hanging over me where someone can jerk the rug out from under me at any time.

“Well, Georgie boy, I’ve got to be toddling along. I’ve got a little job at the supermarket up the street. They put altogether too much confidence in that safe they have. But I’ll be back in a couple of hours, Georgie boy. I’ve collected on part of my investment and now I want to collect on the rest of it. You wait up for me, girlie. You can go get some shut-eye, Georgie.”

Big Larry looked at Stella, walked to the door, stood for a moment searching the shadows, then melted away into the darkness.

“You,” Ollie said to Stella, his voice showing his heartsickness at her betrayal.

“What?” she asked.

“Telling him about the safe — about that hundred dollars, giving him the combination—”

She said, “I couldn’t stand to have him hurt you.”

“You and the things you can’t stand,” Ollie said. “You don’t know Rubber-glove Giffen. You don’t know what you’re in for now. You don’t—”

“Shut up,” she interrupted. “If you’re going to insist on letting other people do your thinking for you, I’m taking on the job.”

He looked at her in surprise.

She walked over to the closet, came out with a wrecking bar. Before he had the faintest idea of what she had in mind she walked over to the cash register, swung the bar over her head, and brought it down with crashing impact on the front of the register. Then she inserted the point of the bar, pried back the chrome steel, and jerked the drawer open.

She went to the back door, unlocked it, stood on the outside, inserted the end of the wrecking bar, and pried at the door until she had crunched the wood of the door jamb.

George Ollie was watching her in motionless stupefaction. “What the devil are you doing?” he asked. “Don’t you realize—?”

“Shut up,” she said. “What’s this you once told me about a spindle job? Oh, yes, you knock off the knob and punch out the spindle—”

She walked over to the safe and swung the wrecking bar down on the knob of the combination, knocking it out of its socket, letting it roll crazily along the floor. Then she went to the kitchen, picked out a towel, and polished the wrecking bar clean of fingerprints.

“Let’s go,” she said to George Ollie.

“Where?” he asked.

“To Yuma,” she said. “We eloped an hour and a half ago — or hadn’t you heard? We’re getting married. There’s no delay or red tape in Arizona. As soon as we cross the state line we’re free to get spliced. You need someone to do your thinking for you. I’m taking the job.

“And,” she went on, as George Ollie stood there, “in this state a husband can’t testify against his wife, and a wife can’t testify against her husband. In view of what I know now, it might be just as well.”

George stood looking at her, seeing something he had never seen before — a fierce, possessive something that frightened him at the same time that it reassured him. She was like a panther protecting her young.

“But I don’t get it,” George said. “What’s the idea of wrecking the place, Stella?”

“Wait until you see the papers,” she told him.

“I still don’t get it,” he told her.

“You will,” she said.

George stood for another moment. Then he walked toward her. Strangely enough he wasn’t thinking of the trap but of the smooth contours under her pale blue uniform. He thought of Yuma, of marriage and of security, of a home.

It wasn’t until two days later that the local newspapers were available in Yuma. There were headlines on an inside page:

The newspaper account went on to state that Mrs. George Ollie had telephoned the society editor from Yuma stating that George Ollie and she had left the night before and had been married across the state line. The society editor had asked her to hold the phone and had the call switched to the police.

Police asked to have George Ollie put on the line. They had a surprise for him. It seemed that when the merchant patrolman had made his regular nightly check of Ollie’s restaurant at one a.m., he found it had been broken into. Police had found a perfect set of fingerprints on the cash register and on the safe. Fast work had served to identify the fingerprints as those of Big Larry Giffen, known in the underworld as Rubber-glove Giffen because of his skill in wearing rubber gloves and never leaving fingerprints. This was one job that Big Larry had messed up. Evidently he had forgotten his gloves.

Police had mug shots of Big Larry and in no time at all they had out a general alarm.

Only that afternoon George Ollie’s head waitress and part-time cashier had gone to the head of the police burglary detail. “In case we should ever be robbed,” she had said, “I’d like to have it so you get a conviction when you find the man who did the job. I left a hundred-dollar bill in the safe. I’ve torn off a corner. Here’s the tom comer. You keep it. That will give you a conviction if you get the thief.”

The police thought it was a fine idea. It was such a clever idea they were sorry they couldn’t have used it to pin a conviction on Larry Giffen.

But Larry had elected to shoot it out with the arresting officers. Knowing his record, officers had been prepared for this. After the sawed-off shotguns had blasted the life out of Big Larry, the police had found the bloodstained hundred-dollar bill in his pocket when his body was stripped at the morgue.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.