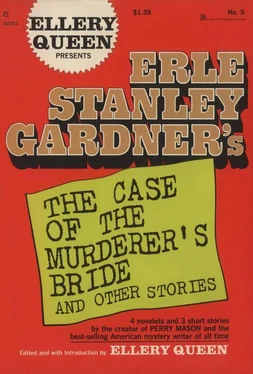

Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Erle Gardner - Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1974, Издательство: Davis Publications, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Davis Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1974

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At length the door was in front of her. Hands pushed against her. The door swung open and she found herself once more in The Alley of the Sky Horse, shuffling along with demure eyes downcast, and a face which was the face of a sleepwalker.

Leung Fah went only so far as the house where the sacrifices were being offered to the spirit of the departed. The ashes of the sacrificial fire were still smoldering in the narrow street, drifting about in vagrant gusts of wind. Leung Fah knew that in this house there would be mourners, that any who were of the faith and desired to join in sending thought waves to the Ancestor in the Beyond would be welcome.

She climbed the stairs and heard chanting. Around the table were grouped seven nuns with heads as bald as A sharp razor could make them. At another table, flickering peanut-oil lamps illuminated a painting of the ancestor who had in turn joined his ancestors. The table. was laden with sacrifices. There were some twenty people in the room who intermittently joined in chanting prayers.

Leung Fah unostentatiously joined this group. Shortly thereafter she moved quietly to the stairs which gave to the roof, and within a half hour had worked her way back to the roof of the house of the three candles. She sought a deep shadow, merged herself within it, and became motionless.

Slowly the hours of the night wore away. Leung Fah began to listen. Her ears, strained toward the east, then heard a peculiar sound. It was like distant thunder over the mountains, a thunder which rumbles ominously.

With terrifying rapidity the murmur of sound in the east grew into a roar. She could hear the screams of people in the streets below, could hear babies, aroused from their sleep as they were snatched up by frantic parents, crying fretfully.

Still Leung Fah remained motionless. The planes swept by overhead. Here and there in the city bright red flares suddenly blossomed into blood-red pools of crimson. And wherever there was a flare, an enemy plane swooped down, and a moment later a mushroom of flame rose up against the night sky, followed by a reverberating report which shook the very foundations of the city.

Leung Fah crept to the edge of the roof where she might peer over and watch The Alley of the Sky Horse. She saw surreptitious figures darting from shadow to shadow, slipping through the portals of the house of three candles.

At length a shadow, more bulky than the rest, the shadow of a fat man running on noiseless feet, crossed the street and was swallowed up in the entrance of the house of three candles. The planes still roared overhead.

Leung Fah placed her box of red fire on the roof and tore off the paper. With calm, untrembling hands, she struck a match to flame, the flame to the flare.

In the crimson pool of light which illuminated all the housetops, Leung Fah fled from one rooftop to another. And yet it seemed she had only been running a few seconds when a giant plane materialized overhead and came roaring down out of the sky. She heard the scream of a torpedo. The entire street rocked under the impact of a stupendous explosion.

Leung Fah was flung to her knees. Her eardrums seemed shattered, her eyes about to burst from their sockets under the enormous rush of pressure which swept along with the blast.

Day was dawning when she recovered enough to limp down to The Alley of the Sky Horse. The roar of the planes was receding into the distance.

Leung Fah hobbled slowly and painfully to the place where the house of the three candles had stood. There was now a deep hole in The Alley of the Sky Horse, a hole surrounded by bits of wreckage and tom bodies.

A blackened torso lay almost at her feet. She examined it intently. It was all that was left of Sahm Seuh.

She turned and limped back up The Alley of the Sky Horse, her eyes downcast and expressionless, her face as though it had been carved of wood.

The sun rose in the east, and the inhabitants of Canton, long since accustomed to having the grim presence of death at their side, prepared to clear away the bodies and debris, to resume once more their daily course of ceaseless activity.

Leung Fah lifted the bamboo yoke to her sore shoulders. Aiiii ah-h-h it was painful, but one must work if one would eat.

Jayson Burr and Gabby Hilman in

Death Rides a Boxcar

When the leg gave its first warning twinge, I stood still for a while and let the rest of the crowd stream on past, up the sloping passenger exit of the big Los Angeles terminal, up to the place where friends and relatives, wives and sweethearts waited in a roped-off space.

It was going to be a job, remembering to favor that leg, but anything was better than hanging around the insipid routine of the hospital.

“Gabby” Hilman was coming by bus. He was to meet me at the Palm Court Hotel around ten o’clock. Until then I was just killing time. I could have started a little celebration over my release from the hospital, but I didn’t want to do it without Gabby. He’d been my buddy, and I wanted to start even with him.

There was no such thing as getting a cab to yourself these days. They piled them in two, three, and four at a time. A starter grabbed the light bag I was carrying. “Where to?” he asked.

“Palm Court Hotel.”

“Get in.”

He held the door open, and that was when I saw class waiting in the cab.

She moved over as I got in. For a moment her eyes rested on mine — large dark eyes that were built to register expression.

I was careful about getting into the cab. “Sorry if I’m a little awkward,” I apologized. “I’m nursing a knee back to life.”

She smiled, but she didn’t say anything.

The cab starter said abruptly, “Where to, sir?” and a man’s voice answered, “The corner of Sixth and Figueroa Street.”

The cab starter said, “Hop in.”

A woman came through the door first, an elderly, white-haired woman with a beaming cheerful face and kindly gray eyes that blinked at me through silver-rimmed spectacles. The man with her looked to be somewhere around 70, so I pulled down the jump seat and moved over. It was rather a slow process because I didn’t want to throw the leg out, and I thought the girl on my left watched me with just a little more interest than she’d shown before.

The elderly woman moved over to the middle of the seat, the man got in on the right side. The cab door slammed, and we were off.

It was a short run to Sixth and Figueroa. The man and the woman got off. The girl said to me, “If you’re going much farther, you’d better come back to a more comfortable seat.”

“Thanks,” I told her, and moved back.

Her eyes were solicitous as she watched the way I moved my leg. “Hurt?” she asked.

“It’s just a habit,” I told her. “It will take some time to get accustomed to throwing the leg around.”

She didn’t say anything more for a while, and not knowing just how far she was going I decided I’d have to work fast. I took a notebook from my pocket, pulled out a pencil, and said, “I’m an investigator gathering statistics for a Gallup poll. These are questions we have to ask in the line of duty. Have you purchased war bonds? — Not the amount; just yes or no.”

She looked at me with a peculiar, half-quizzical expression, and said shortly, “Yes.”

“Question Number Two,” I went blithely on. “Do you feel sympathetic toward the personnel in the armed forces?”

“Of course.”

“Question Number Three. Recognizing the fact that members of the armed forces whom you may encounter are frequently far from home, inclined to be lonely, and with no personal contacts, do you feel it is not only all right, but commendable, to let them make your acquaintance and perhaps, under favorable circumstances, act as your escort for an evening?”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Murderer’s Bride and Other Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.