“Serle has sold us outright. Naturally, you’d have to expect that. I think that he talked with Conway at ten-thirty, but he’s fixed the time at ten o’clock now. Of course, there wasn’t any bribery or anything like that, but, as one of the main witnesses for the prosecution, the D.A. wouldn’t want him to come into court as a crook. So they’re covering him with a thick coat of whitewash; and, of course, Serle was smart enough to figure that all out. He didn’t have to be awfully smart to do that.

“Incidentally, while we’re checking up on things, don’t overlook this prospector friend of Leeds — Ned Barkler.”

“What about him?” Mason asked.

“He’s a card,” Drake said, “talks occasionally about the old days in the Yukon country, never mentions any of his own adventures, becomes interested in stories of frontier brawls, and shooting scrapes. For the most part, he wears disreputable clothes, but occasionally he spruces himself up and steps out. He looks the girls over with an appraising eye, and makes passes at the pretty ones when he thinks he can get away with it — cashiers in restaurants, girls at cigar counter, manicurists, and janes like that.”

“Successful?” Mason asked.

“Hell, Perry,” the detective protested. “Give me a chance. I haven’t even located him yet. He’s a colorful profane old coot who’s as salty as a piece of smoked salmon. But where the devil he came from before he contacted Leeds, is more than I can find out. He appeared a couple of years ago, right in the middle of the picture. And now that he’s left, he’s walked right out of the middle of the picture. Somehow, Perry, I have an idea there’s one man we’ll never find until he wants us to find him.”

Mason said, “I want Inez Colton, Paul, and I want her badly.”

“How much time can I have?” Drake asked.

“None at all,” Mason said. “I’m going to rush that preliminary hearing through just as fast as I can.”

“Why not stall along until I can turn up something on the Colton woman?”

Mason shook his head. “Don’t forget the D.A. has served a subpoena duces tecum on my handwriting expert. I want to mix this case up so much and rush it through so fast that he’ll be one jump behind us all the way along the line. When he sees those papers, I don’t want him to have time enough to figure out what they mean.”

“It’ll take work and luck,” Drake said. “I’ll furnish the work. You’ll have to pray for luck. What’s all this about Milicant being Hogarty, Perry, and how did you find out about that frostbitten foot?”

Mason smiled at Della Street. “A little bird told me,” he said.

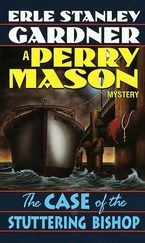

Judge Knox, who had acquired a great respect for Perry Mason’s courtroom technique, by presiding over the preliminary hearing in what the press had subsequently referred to as “The Case of the Stuttering Bishop,” gazed down on the crowded courtroom, and said, “Gentlemen, in the Case of the People of the State of California versus Alden Leeds, accused of the murder of John Milicant, sometimes known as Bill Hogarty, also referred to as L. C. Conway, the defendant has previously been advised of his constitutional rights. This is the time heretofore fixed pursuant to stipulation for the preliminary hearing. Are you ready?”

Bob Kittering, of the district attorney’s office, a thin, nervous individual with restless eyes, answered, “Ready on behalf of the People, Your Honor.”

“Ready for the defendant,” Mason said.

“Proceed,” Judge Knox instructed.

The deputy coroner was the first witness. He testified at length concerning the finding of the body, introduced photographs showing its position on the floor of the bathroom, showing the fatal knife which protruded from the back, just above the left shoulder blade. He also produced photographs showing the state of the apartment with the evidences of hasty search. Under further questioning by Kittering, he produced an envelope which contained the personal possessions of the decedent which had been taken from the pockets of his clothes.

Kittering said, “I observe that there is a fountain pen, a handkerchief, a jackknife, six dollars and twelve cents in loose change found in the trousers pocket of the deceased, an envelope with no return address, addressed to L. C. Conway, and containing scribbled memoranda. There is a pigskin key container, a watch, a cigarette case, and a pocket lighter. I call your attention to the fact that there is no wallet, no driving license, no business cards, and no currency, and ask you if you are absolutely certain that these items and these items alone were all that you found in the clothes of the deceased.”

“That is correct,” the deputy coroner said.

“No wallet was found in the clothing, and none was subsequently found in the apartment?”

“So far as I know, that is correct. No wallet was ever discovered.”

“Take the witness,” Kittering said.

“No cross-examination,” Mason announced urbanely.

The autopsy surgeon was called and testified at some length. He commented on the fact that from the state of the body, as he had discovered it, death had been caused by a downward thrust of a long-handled carving-knife which was still imbedded in the wound. This instrument had been inserted on a downward slope, clearing the left shoulder blade and penetrating the heart.

Death, in his opinion, had been instantaneous.

The time of death he fixed as approximately from eight to fourteen hours prior to the time he had made his examination.

Kittering produced a bloodstained carving knife. “I call your attention to this knife, Doctor, and ask you if this is the knife which you found imbedded in the body of the decedent?”

“It is,” the doctor said.

Kittering asked that the knife be marked for identification as People’s Exhibit A.

“No objection,” Mason drawled.

“Can you,” Kittering asked, “fix the time of death any more definitely than that, Doctor?”

“Not in relation to the time when I examined the body, but I can fix it very definitely in regard to the contents of the stomach.”

“What do you mean, Doctor?”

“I mean that in examining the contents of the stomach, and submitting them to an examination for the purposes of detecting the possible presence of poison, we found that the person in question had died approximately two hours after a meal consisting primarily of mutton, probably in the form of chops, green peas, and potatoes, had been consumed... In order to explain my answer, I may state that while the time of death as fixed in postmortem depends upon various elastic factors such as rigor mortis, the cooling of the body, etc., and is, therefore, subject to a certain amount of individual variation, the processes of digestion are more uniform; and by examining the state to which those digestive processes have progressed prior to death, we can, when there is food in the stomach, fix the time of death with much greater nicety.”

“Can you,” Kittering asked, “fix the exact time of death?”

“In view of the evidence,” the doctor said positively, “I fix the time of death definitely as not before ten o’clock in the evening preceding that of the day in which the body was discovered and not later then ten-forty-five on the evening of said day.”

“How do you fix that time?” Kittering asked.

“By an examination of the extent to which the digestive processes had functioned, in connection with the time at which the last meal had been consumed.”

Kittering said triumphantly, “You may inquire.”

Mason said to the court, “Of course, Your Honor, I could move to strike out this entire testimony on the theory that it is predicated upon facts which are beyond the doctor’s knowledge.”

Читать дальше