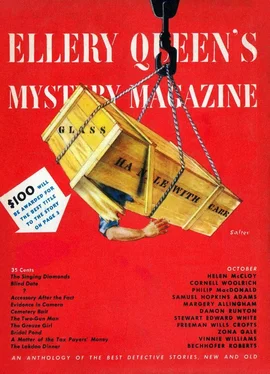

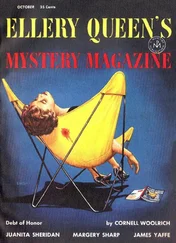

Марджери Аллингем - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Марджери Аллингем - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1949, Издательство: The American Mercury, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949

- Автор:

- Издательство:The American Mercury

- Жанр:

- Год:1949

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Her husband took his horse round and stalled him. Presently he came in. They stood a moment together in silence as their custom was, and she leaned her forehead against his shoulder. Then she busied herself with his supper, and he sat down heavily at the little table.

“Had you any difficulty this time in getting the money together?” she asked.

Her husband was a tax collector.

“None,” he said abstractedly, “at least — yes — a little. But I have it all, and the arrears as well. It makes a large sum.”

He was evidently thinking of something else. She did not speak again. She saw something was troubling him.

“I heard news today at Phillip’s,” he said at last, “which I don’t like. If I had heard in time, and if I could have borrowed a fresh horse, I would have ridden straight on. But it was too late in the day to be safe, and you would have been anxious what had become of me if I had been out all night with all this money on me. I shall go tomorrow as soon as it is light.”

They discussed the business which took him to the nearest town thirty miles away, where their small savings were invested — somewhat precariously, as it turned out. What was safe, who was safe while the invisible war between North and South smouldered on and on? It had not come near them, but as an earthquake which is engulfing cities in one part of Europe will rattle a teacup without oversetting it on a cottage shelf half a continent away — so the Civil War had reached them at last.

“I take a hopeful view,” he said, but his face was overcast. “I don’t see why we should lose the little we have. It has been hard enough to scrape it together, God knows. Promptitude and joint action with Reynolds will probably save it. But I must be prompt.” He still spoke abstractedly, as if even now he were thinking of something else.

He began to take out of the leathern satchel various bags of money.

“Shall I help you to count it?”

She often did so.

They counted the flimsy dirty paper money together, and put it all back into the various labeled bags.

“It comes right,” he said.

Suddenly she said, “But you can’t pay it into the bank tomorrow if you go on to—”

“I know,” he said, looking at her; “that is what I have been thinking of ever since I heard Phillip’s news. I don’t like leaving you with all this money in the house, but I must.”

She was silent. She was not frightened for herself, but it was state money, not their own. She was not nervous as he was, but she had always shared with him a certain dread of those bulging bags, and had always been thankful to see him return safe — he never went twice by the same track — after paying the money in. In those wild days when men went armed with their lives in their hands, it was not well to be known to have large sums about you.

He looked at the bags, frowning.

“I am not afraid,” she said.

“There is no real need to be,” he said after a moment. “When I leave tomorrow morning it will be thought I have gone to pay it in. Still—”

He did not finish his sentence, but she knew what was in his mind: the great loneliness of the prairie. Out in the white night came the short, sharp yap of a wolf.

“I am not afraid,” she said again.

“I shall only be gone one night,” he said.

“I have often been a night alone.”

“I know,” he said, “but somehow it’s worse leaving you with so much money in the house.”

“No one knows it will be here.”

“That is true,” he said, “except that everyone knows I have been collecting large sums.”

“They will think you have gone to pay it in as usual.”

“Yes,” he said with an effort.

Then he got up, and went to his tool box. She watched him open it, seeing him in a new light, which encompassed him with even greater love. “If I tell him tonight,” she thought, “it will make him even more anxious about leaving me. Perhaps he would refuse to go, and he must go. I will not tell him till he comes back.”

The resolution not to speak was like taking hold of a piece of iron in frost. She had not known it would hurt so much. A new tremulousness, sweet and strange, passed over her — not cowardice, not fear, not of the heart nor of the mind, but a sort of emotion of the whole being.

“I will not tell him,” she said again.

Her husband got out his tools, took up a plank from the floor, and put the money into a hole beneath it, beside their small valuables, such as they were, in a biscuit tin. Then he replaced the plank, screwed it down, and she drew back a small fur mat over the place. He put away the tools and then came and stood in front of her. He was not conscious of her transfiguration, and she dropped her eyes for fear of showing it.

“I shall start early,” he said, “as soon as it is light, and I shall be back before sundown the day after tomorrow. I know it is unreasonable, but I shall go easier in my mind if you will promise me one thing.”

“What is it?”

“Not to go out of the house, or to let anyone else come in on any pretense whatever, while I am away,” he said. “Bar everything, and stay inside.”

“I shan’t want to go out.”

He made an impatient movement.

“Promise me that come what will you will let no one in during my absence,” he said.

“I promise.”

“Swear it.”

She hesitated.

“Swear it to please me,” he said.

“I swear that I will let no one into the house, on any pretext whatever, until you come back,” she said, smiling at him.

He sighed and relapsed into his chair, and gave way to the great fatigue that possessed him.

The next morning he started soon after daybreak, but not until he had brought her in sufficient fuel to last several days. There had been more snow in the night, fine snow like salt, but not enough to make traveling difficult. She watched him ride away, and silenced the voice within her which always said as she saw him go, “You will never see him again, you have heard his voice for the last time.” Perhaps, after all, the difference between the brave and the cowardly lies in how they deal with that voice. Both hear it. She silenced it instantly. It spoke again, more insistently: “You have heard his voice, felt his kiss, for the last time. He will never see the face of his child.” She silenced it again, and went about her work.

The day passed as countless other days had passed. She was accustomed to be much alone. She had work to do, enough and to spare, within the little home which was to become a real home, please God, in the spring. The evening fell almost before she expected it. She locked and barred the doors, and closed the shutters of the windows. She made all secure, as she had done many a time before.

A wandering wind had arisen at nightfall, and it came softly across the snow and tried the doors and windows as with a furtive hand. She could hear it coming as from an immense distance, passing with a sigh, returning plaintive, homeless, forlorn, to whisper round the house.

How like the sound of the wind was to wandering footsteps, slowly drawing near, creeping round the house. She could almost have fancied that a hand touched the shutters, was even now trying to raise the latch of the door.

A moment of intense silence, in which the wind seemed to hold its breath and listen without, while she listened within, and then a low, distinct knock upon the door.

She did not move.

“It is the wind,” she said to herself; but she knew it was not.

The knock came again, low, urgent, not to be denied.

She had become very cold. She had supposed fear was an emotion of the mind. She had not reckoned for this slow paralysis of the body.

She managed to creep to the window and unbar the shutter an inch or two. By pressing her face against the extreme corner of the pane she could just discern in the snow-light part of a man’s figure, wrapped in a long cloak.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

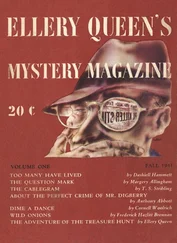

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 14, No. 71, October 1949» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.