“Good shooting!” Papa was saying. “Pull it by yourself?”

“I cooperated with Detectives Hooley and Strong. I am sure the subterfuge was as obvious to them as to me.”

But even as I spoke a doubt arose in my mind. There was, it seemed to me, a possibility, however slight, that the police detectives had not seen the solution as clearly as I had. At the time I had assumed that Sergeant Hooley was attempting to conceal his knowledge from me; but now, viewing the situation in retrospect, I suspected that what the sergeant had been concealing was his lack of knowledge.

However, that was not important. What was important was that, in the image of jewels among vegetables, I had found a figure of incongruity for my sonnet.

Excusing myself, I left Papa’s office for my own, where, with rhyming dictionary, thesaurus, and carbon copy on my desk again, I lost myself in the business of clothing my new simile with suitable words, thankful indeed that the sonnet had been written in the Shakespearean rather than the Italian form, so that a change in the rhyme of the last two lines would not necessitate similar alterations in other lines.

Time passed, and then I was leaning back in my chair, experiencing that unique satisfaction that Papa felt when he had apprehended some especially elusive criminal. I could not help smiling when I reread my new concluding couplet.

And shining there, no less inaptly shone

Than diamonds in a spinach garden sown .

That, I fancied, would satisfy the editor of The Jongleur .

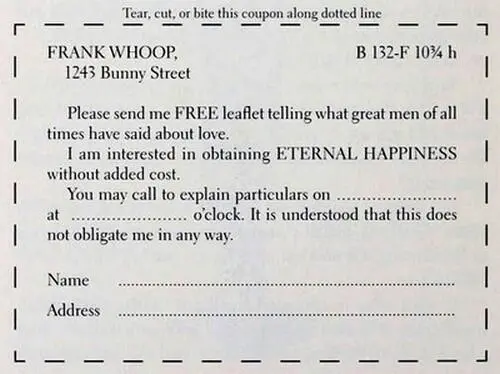

The Advertising Man Writes a Love Letter

Judge, February 26, 1927

Dear Maggie:

I LOVE YOU!

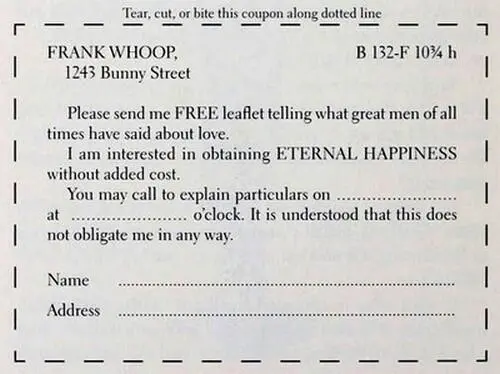

What is love? It is all in all, said Rossetti; it is the salt of life, said Sheffield; it is more than riches, said Lucas; it is like the measles, said Jerome. Send for leaflet telling what these and other great men of all times have said about love! It is FREE!

WILL YOU MARRY ME?

Will you be the grandmother of my grandchildren? Or will you, as thousands of others have done, put it off until too late — until you are doomed to the penalty of a lonely old age? Do not delay. Grandchildren are permanent investments in companionship!

But simply to marry is not enough! You must ask yourself to whom? Shall you marry a man just because you like his eyes, or his dancing? Or will you insist on the best? IT COSTS NO MORE!

A man who is educated, brilliant, witty, thoughtful, handsome, affectionate, honorable and generous — a man who is made of the best moral, mental and physical materials obtainable — a man in every way worthy, not only of being grandfather to your grandchildren, but great-great-grandfather to your great-great-grandchildren.

All this can he yours if you act NOW!

Read what others have said (full names and addresses on request):

“He was one swell guy.” — Flora B—.

“In the four years we roomed together he never once left a ring in the bathtub.” — Paul G—.

“I laughed more the months I knew him than at any other time in my life.” — Fanny S—.

“He’s one of those fellows who knows everything.” — Doris L—.

All this can be yours! Can you afford to be without it?

Mail the coupon TODAY!

Yours for prompt action,

FRANK.

The Bookman, September 1927

A plague on these women who, lengthily wooed,

Are not to be won till one’s out of the mood,

And who then discerning one’s temperateness

Accuse one of cooling because they said yes!

Detective Fiction Weekly, October 19, 1929, as Samuel Dashiell

I always knew West was eccentric.

Ever since the days of our youth, in various universities — for we seemed destined to follow each other about the globe — I had known Alexander West to be a person of the most bizarre, though not unattractive, personality: At Heidelberg, where he renounced water as a beverage; at Pisa, where he affected a one-piece garment for months; at the Sorbonne, where he consorted with the most notorious characters, boasting an acquaintance with Le Grand Raoul, an unspeakable ruffian of La Villette.

And in later life, when we met in Constantinople, where West was American minister, I found that his idiosyncrasies were common topics in the diplomatic corps. In the then Turkish capital I naturally dined with West at the Legation, and except for his pointed beard and Prussian mustache being somewhat more gray, I found him the same tall, courtly figure, with a keen brown eye and the hands of generations, an aristocrat.

But his eccentricities were then of more refined fantasy. No more baths in snow, no more beer orgies, no more Libyan negroes opening the door, no more strange diets. At the Legation, West specialized in rugs and gems. He had a museum in carpets. He had even abandoned his old practice of having the valet call him every morning at eight o’clock with a gramophone record.

I left the Legation thinking West had reformed. “Rugs and precious stones,” I reflected; “that’s such a banal combination for West.” Although I did recall that he had told me he was doing something strange with a boat on the Bosporus; but I neglected to inquire about the details. It was something in connection with work, as he had said, “Everybody has a pleasure boat; I have a work boat, where I can be alone.” But that is all I retained concerning this freak of his mind.

It was some years later, however, when West had retired from diplomacy, that he turned up in my Paris apartment, a little grayer, straight and keen as usual, but with his beard a trifle less pointed — and, let’s say, a trifle less distinguished-looking. He looked more the successful business man than the traditional diplomat. It was a cold, blustery night, so I bade West sit down by my fire and tell me of his adventures; for I knew he had not been idle since leaving Constantinople.

“No, I am not doing anything,” he answered, after a pause, in reply to my question as to his present activities. “Just resting and laughing to myself over a little prank I played on a friend.”

“Oho!” I declared; “so you’re going in for pranks now.”

He laughed heartily. I could hardly see West as a practical joker. That was one thing out of his line. As he held his long, thin hands together, I noticed an exceptionally fine diamond ring on his left hand. It was of an unusual luster, deep set in gold, flush with the cutting. His quick eye caught me looking at this ornament. As I recall, West had never affected jewelry of any kind.

“Oh, yes, you are wondering about this,” he said, gazing into the crystal. “Fine yellow diamond; not so rare, but unusual, set in gold, which they are not wearing any longer. A little present.” He repeated blandly, after a pause, “A little present for stealing.”

“For stealing?” I inquired, astonished. I could hardly believe West would steal. He would not play practical jokes and he would not steal.

“Yes,” he drawled, leaning back away from the fire. “I had to steal about four million francs — that is, four million francs’ worth of jewels.” He noted the effect on me, and went on in a matter-of-fact way: “Yes, I stole it, stole it all. Got the police all upset; got stories in the newspapers. They referred to me as a super-thief, a master criminal, a malefactor, a crook, and an organized gang. But I proved my case. I lifted four million from a Paris jeweler, walked around town with it, gave my victim an uncomfortable night, and walked in his store the next day between rows of wise gentlemen, gave him back his paltry four million, and collected my bet, which is this ring you see here.”

Читать дальше