At six o’clock the sound came of the elevator complaining as it started down, but it only lasted four seconds. He had stopped off for a look at the South Room, which he hadn’t seen since one-thirty Tuesday morning. It was a good ten minutes before it started again, so he gave the ruins more than a glance. When he came and crossed to his desk and got settled, he said my guess of fifteen hundred dollars was probably too low with the bloated prices of everything from sugar to shingles, and I said I was glad to hear him having fun with words, tossing off an alliteration with two words that weren’t spelled the same. He said it had been casual, which was a lie, and started reading and signing the letters. He always reads them, not to catch errors, because he knows there won’t be any, but to let me know that if I ever make one it will be spotted.

It was ten minutes to seven and I was sealing the envelopes when the phone rang and I got it.

“Nero Wolfe’s residence, Archie Goodwin speaking.” Up to six o’clock it’s “office.” After six, “residence.” I don’t want people to think my nose is on the grindstone. Most offices close at five.

“May I speak to Mr. Wolfe, please? My name is Roman Vilar . V–I-L-A-R.”

I covered the mouthpiece and turned. “Fred has flushed one. Roman Vilar, euphemistic security. He asks permission to speak to Mr. Wolfe, please. Only he makes it Vi- lar .”

“Indeed.” Wolfe reached for his receiver. I kept mine.

“Nero Wolfe speaking.”

“This is Roman Vilar, Mr. Wolfe. You have never heard of me, but of course I have heard of you. But that isn’t correct — you have heard of me, or at least your man Goodwin has. Yesterday, from Benjamin Igoe.”

“Yes. Mr. Goodwin has told me.”

“Of course. And he told you what Mr. Igoe told him. Of course. And Mr. Igoe has told me what he told Goodwin. I have told others, and they are here with me now in my apartment. Mr. Igoe and four others. May I ask a question?”

“Yes. I may answer it.”

“Thank you. Have you told the police or the District Attorney what Mr. Igoe told Goodwin?”

“No.”

“Thank you. Do you intend to? No, I withdraw that. I can’t expect you to tell me what you intend to do. We have been discussing the situation, and one of us was going to go and discuss it with you, but we decided we would all like to be present. Of course not now — it’s your dinnertime, or soon will be. Would nine o’clock be convenient?”

“Here. At my office.”

“Certainly.”

“You know the address.”

“Certainly.”

“You said four others. Who are they?”

“You have their names. Mr. Igoe gave them to Goodwin.”

“Yes. We’ll expect you at nine o’clock.”

Wolfe hung up. So did I.

“I want a raise,” I said. “Beginning yesterday at four o’clock. I admit it will be more inflation, and President Ford expects us to voluntarily lay off, but as somebody said, a man is worth his hire. It took me just ten minutes to get Igoe to spill that.”

“ ‘The laborer is worthy of his hire.’ The Bible. Luke. They offered to work for nothing, all three of them, and you want a raise, and it was you who took him up to bed.”

I nodded. “And you said to me with him there on the floor and plaster all around him and on him, ‘I suppose you had to.’ Someday that will have to be fully discussed, but not now. We’re talking just to show how different we are. If we were just ordinary people we would be shaking hands and beaming at each other or dancing a jig. It’s your turn.”

Fritz entered. To announce a meal he always comes in three steps, never four. But seeing us, when he stopped, what he said was, “Something happened.”

Damn it, we were and are different. But Fritz knows us. He ought to.

Before going to the dining room I rang Saul’s number, got his answering service, and left a message that I couldn’t make it to the weekly poker game and give Lon Cohen my love.

The only visible evidence in the office that we had company was six men on chairs. Since this was a family affair, not business, it could be mentioned at the table, and after the cognac flames on a roast duck Mr. Richards had died, and Wolfe had carved it, and Fritz had brought me mine and taken his, we had discussed the question of setting up a refreshment table and had vetoed it. It would have made them think they were welcome and we wished them well, which would have been only half true. They were welcome, but we did not wish them well — at least not one of them.

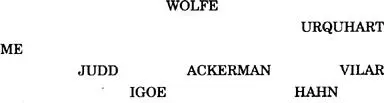

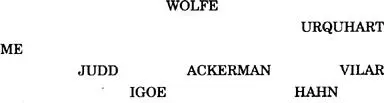

To a stranger entering the office it’s obvious at a glance that the red leather chair is the place. I had intended to put Benjamin Igoe in it, but a bishop with a splendid mop of white hair and quick gray eyes went to it even before he pronounced his name. Ernest Urquhart, the lobbyist. They all pronounced their names for Wolfe before they sat — the other five on two rows of yellow chairs facing Wolfe’s desk, three in front and two back. Like this:

“I’m not really arrogant or impudent, Mr. Wolfe,” Urquhart said. “I took this chair only because these gentlemen decided that, since we are all willing talkers, it would be wise to name a spokesman, and they chose me. Not that their tongues are tied. Two of them are lawyers. I can’t say with Sir Thomas More, ‘and not a lawyer among them.’ ”

Not a good start. Wolfe didn’t like quoters, and he was down on More because he had smeared Richard III. I was wondering whether Urquhart was a lobbyist because he looked like a tolerant and sympathetic bishop, or looked like that because he was a lobbyist. He had the voice for it, too.

“I have all night,” Wolfe said.

“It shouldn’t take all night. We certainly hope not. As you must have gathered from what Mr. Vilar said on the phone, we’re concerned about what Mr. Igoe told Mr. Goodwin about Mr. Bassett — and what Mr. Goodwin told him. Frankly, we think it was unnecessary and indiscreet, and—”

“Leave that out! Goddam it, I told you.” It was Igoe’s strong baritone, even stronger.

“That was understood, Ernie.” Ackerman. Francis Ackerman, lawyer, Washington. I am not going to drag in Watergate, it certainly doesn’t need any dragging in by me, but when they had single-filed in from the stoop he had struck me as a fairly good take-off of John Mitchell, with his saggy jowls and scanty chin. His calling Ackerman “Ernie” showed that he was the kind of Washington lawyer who is on nickname terms with lobbyists. Anyhow, one lobbyist.

Urquhart nodded. Not to Ackerman or Igoe or Wolfe; he just nodded. “That slipped out,” he told Wolfe. “Please ignore it. What concerns us is the possible result of what Mr. Igoe told Mr. Goodwin. And he gave him our names, and today men have been making inquiries about two of us, and apparently they were sent by you. Were they? Sent by you?”

“Yes,” Wolfe said.

“You admit it?”

Wolfe wiggled a finger. That was regression — I just looked it up. He had quit finger-wiggling a couple of years back. “Don’t do that,” he said. “Calling a statement an admission is one of the oldest and scrubbiest lawyers’ tricks, and you’re not a lawyer. I state it.”

“You’ll have to make allowances,” Urquhart said. “We are not only concerned, we are disturbed. Apprehensive. Mr. Goodwin told Mr. Igoe that at that dinner at Rusterman’s one of us handed Mr. Bassett a slip of paper, and—”

“No.”

“No?”

“He told Mr. Igoe that Pierre Ducos had told him that he had seen one of you hand Mr. Bassett a slip of paper. Also that that was the one fact that Pierre had mentioned, and that therefore we considered it significant.”

Читать дальше