“Forbid you to have anything to do with Marvin Adams, to see him, write to him, or talk with him on the telephone.”

“I don’t care what Marvin’s father did. I don’t care who he was. I love him. Do you understand, Mr. Mason? I love him !”

“I understand,” Mason said. “I don’t think your father does.”

“But,” she said, “this is — this is — Mr. Mason, are you certain? Are you absolutely certain that what Mrs. Adams said about the kidnaping wasn’t true?”

“Apparently there’s no question about it.”

“And his father was convicted of murder and — and hanged?”

“Yes.”

“And you say his father was guilty?”

“No.”

“I thought that was what you said.”

“No. I said that, from an examination of the record, I couldn’t find any proof that he was innocent.”

“Well, doesn’t that amount to the same thing?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“In the first place, my examination was limited to the record. In the second place, I found some things which indicated his innocence, but that wasn’t proof. However, I am hoping to prove that he was innocent, from things which didn’t appear in the record, but which are beginning to come out now.”

“Oh, Mr. Mason, if you could only do that!”

“But,” Mason went on, “in case the police should start investigating Marvin’s background, find out about this old murder case, and air it in the newspapers, my work would be exceedingly difficult. Even after I had accomplished it, it wouldn’t be effective. Once people get the idea that Marvin’s father was a murderer, I can come along a few days, or perhaps a few weeks, later, and prove that he wasn’t. People will always think it was some sort of hocus-pocus that was worked out by a high-priced attorney who was hired by a millionaire father-in-law so that Marvin could be whitewashed. They’ll be whispering stories about him behind his back as long as he lives.”

“I don’t care,” she said. “I’ll marry him anyway.”

“Sure,” Mason said. “You don’t care. You can take it. But how about Marvin? How about your children?”

Her silence showed how forcefully that thought had struck her.

Mason went on, “Marvin is sensitive. He’s enthusiastic. He’s keen to get along. He didn’t have much when he went to school, didn’t have much in the way of clothes, didn’t have much in the way of spending money; but he had personality. He had something which made him a leader. He was president of his class in high school. He was the editor of the high-school paper. Now, in college, he’s popular and successful. People like him and he responds to their liking. Take that away from him. Let him be placed in such a position that people are whispering behind his back, and conversation stops whenever he comes into a room. That...”

“Stop it!” she cried.

Mason said, “I’m talking facts.”

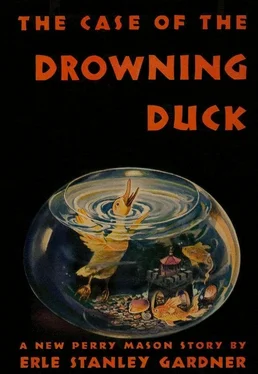

“Well, you can’t let my father be convicted on account of a duck...”

Mason said, “That duck will have absolutely nothing to do with your father’s conviction or acquittal so far as the murder of Roland Burr is concerned. It was simply a statement he made about the duck which caused the police to become suspicious of him in the first place. The only way to acquit your father is to find out who gave Roland Burr that fishing rod.”

“How are we going to do that?” she asked. “The servants all say they didn’t. There was no one else in the house. Mrs. Burr had gone to town with the doctor, and according to the testimony of both the doctor and Mrs. Burr, the fishing rod was one of the last things Roland Burr asked for before they went out. It was while all three of them were in the room together, and they all went out at the same time.”

“That makes it look very bad indeed,” Mason admitted.

“Mr. Mason, can’t you do something ?”

“Your father doesn’t want me to represent him as his lawyer.”

“Why not?”

“Because I insisted on pointing out to him the similarity of the predicament in which he now finds himself, and that in which Horace Adams found himself some eighteen years ago. Your father doesn’t like that. His position was that the Witherspoon family couldn’t afford to have an affiliation with the family of someone who had even been charged with murder.”

“Poor Dad. I know just how he feels. Family means so much to him. He’s always been so proud of our family.”

“It might be a good plan for him to get jolted out of that,” Mason said. “It might be a good thing for all of us to get jolted out of it.”

“I’m afraid I don’t follow you.”

“We’ve been taking too much for granted simply because of our ancestors. We’ve hypnotized ourselves. We keep saying proudly that other nations should be afraid of us because we never have lost a war. We should put it the other way. It might be a good thing for us all to learn that we have to stand on our own two feet — beginning with your father.”

She said, “I love my father, and I love Marvin.”

“Of course, you do,” Mason said.

“I’m not going to sacrifice one for the other.”

Mason shrugged his shoulders.

“Mr. Mason, can’t you understand? I’m not going to let my father’s position become jeopardized because I planted that duck in Marvin’s car.”

“I understand.”

“You don’t seem to be of very much help.”

“I don’t think anyone can help you, Lois. It’s something you’ve got to decide for yourself.”

“Well, it makes a difference to you, doesn’t it?”

“Probably.”

“Can’t you think of some way out?”

Mason said, “If you tell the authorities about having planted that duck in Marvin’s car, you’re going to get yourself out of a very hot frying pan into a very hot fire. It won’t get your father out of it — not now. It will simply get Marvin in.”

“If it hadn’t been for the duck, they never would have started suspecting Father.”

“That’s all right, but they’ve started now. They’ve uncovered enough evidence so they’re not going to back up. You might find yourself facing the situation of having your father tried for the murder of Roland Burr, and Marvin on trial for the murder of Leslie Milter. Wouldn’t that be something?”

She said, “I don’t like the idea of temporizing with my conscience because of results. I think it’s better to do what you think is right, and let the results take care of themselves.”

“And what do you think is the right thing to do?”

“Tell the authorities about that duck.”

“Would you promise to wait a few days?” Mason asked.

“No. I won’t promise. But I — well, I’ll think it over.”

“All right,” Mason said, “do that.”

She looked as though she would have liked to cry on his shoulder, but she summoned her pride, and walked out of the room with her chin held very high.

Mason went down to Della Street’s room, tapped on the door.

Della Street, her eyes anxious, flung the door open. “What did she want, Chief?”

Mason smiled. “She wanted to get squared with her conscience.”

“About that duck?”

“Yes.”

“What’s she going to do?”

“Eventually she’s going to tell all about it.”

“What will that do — to you?”

“It will leave me in something of a spot down here,” Mason said.

“And I suppose that’s looking at it optimistically?”

His smile became a grin. “I always look at things optimistically.”

“How long will she give you to work out some solution?”

“She doesn’t know herself.”

Читать дальше