Erle Gardner - The Seven Sinister Sombreros

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Erle Gardner - The Seven Sinister Sombreros» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1939, Издательство: Street & Smith Publications, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

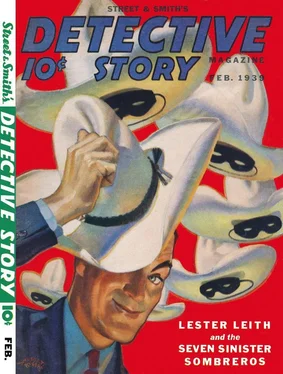

- Название:The Seven Sinister Sombreros

- Автор:

- Издательство:Street & Smith Publications

- Жанр:

- Год:1939

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Seven Sinister Sombreros: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Seven Sinister Sombreros»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Seven Sinister Sombreros — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Seven Sinister Sombreros», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The undercover man’s doubts showed in his eyes. The huge hat, with its high crown and wide brim, seemed to throw Leith off balance. It was as though the hat were wearing the man rather than the man wearing the hat.

The spy coughed deprecatingly.

Leith glanced at him sharply. “What’s the matter, Scuttle?”

“Begging your pardon, sir,” the spy said, “but if you don’t mind my saying so, sir, I thought that hat you were wearing was very becoming, very becoming indeed.”

“Meaning that you don’t like this one as well, Scuttle?”

“Oh, I’d hardly say that, sir. After all, this cowboy regalia is a bit strange to me. That first hat, sir, was very becoming, very becoming indeed.”

Leith said dubiously: “I can see that you’re being tactful, Scuttle. Don’t do it. I like this big hat. When I want a cowboy hat, I want a real one. I shall wear this.”

“Yes, sir. Very good, sir.”

“And, Scuttle, how many more of those sombreros do we have?”

“Two, sir.”

“Put them all in the car,” Leith said. “If I decide that this hat is too large, I’ll change all those others for smaller hats.”

A cunning glint came into the eyes of the spy. “Begging your pardon, sir,” he said, “but you can only wear one hat at a time.”

Lester Leith surveyed his valet thoughtfully. “Scuttle,” he said, “never make positive statements to me in that tone of voice. It irritates me. It acts as a challenge, and it’s not correct. After all, Scuttle, hats are made to telescope. Dealers carry them that way on their shelves. There’s no reason why a man couldn’t wear four or five hats, one on top of the other.”

“Yes, sir,” the spy said. “Very good, sir. It is, of course, quite readily conceivable.”

“That’s better, Scuttle,” Leith said. “Now bring those hats down to the car.”

Leith walked back to the elevators, descended to the lobby, and clumped-clumped-clumped out to the street where his car was parked. A few persons who happened to be in the lobby eyed him curiously, and then turned to exchange amused glances with each other. But Leith, seemingly oblivious of their stares, marched across to the automobile.

As Lester Leith pulled away from the curb, an inconspicuous car, neither old nor new, neither shiny nor shabby, slid out from the mouth of an alley and started following Leith’s car. The man at the wheel was broad-shouldered, thick-necked, and his eyes had that peculiarly insistent, boring belligerency which comes to men who have been long on the police force.

Two men occupied the rear seat of the automobile, sitting well back with the brims of their hats pulled low on their foreheads so as to shade their eyes as well as conceal their faces. The man on the left was Sergeant Ackley. The one on the right was Captain Andrew Carmichael.

Captain Carmichael was staring thoughtfully at the car ahead as they speeded down the boulevard. “Look here, Ackley,” he said. “This thing doesn’t make sense.”

“It never does,” Sergeant Ackley said. “He fixes it so it don’t.”

“Don’t be impertinent!”

“I’m not being impertinent, captain. That’s the thing about Leith which makes him so dangerous. He reasons along entirely unconventional lines. I’ve worked on him enough now so I’m commencing to know something of his methods.”

Captain Carmichael said angrily: “Well, this time he’s just taking you on a wild-goose chase. He could no more hijack money in an outfit like that then he could fly to the moon. Look at the way everyone stares at him. He’s a walking side show. He might just as well be carrying a brass band with him.”

Sergeant Ackley said with feeling: “And don’t think that man couldn’t walk in right under your nose and hijack a bunch of loot with a brass band. That’s just his style.”

Captain Carmichael puckered his forehead. “I certainly hope,” he said, “that you know what you’re doing.”

“I do,” Ackley said. “I’ve got him this time. He’s hot on the trail of this hundred thousand dollars. What’s more, he’s going to get it, and when he does, we’re going to get him. This is one time we’re properly prepared. You see, captain, on the other occasions we’ve known what Leith was doing, but we didn’t know what he expected to accomplish by doing it because we didn’t know who was guilty. This time we’ve got the whole thing doped out, because we know Bradercrust is the one he’s after. Always before, Leith has been one jump ahead of us. This time he ain’t.”

Captain Carmichael said: “That was an interesting bit of reasoning, that report of yours, sergeant. I sent it on to the chief. He seemed very much pleased with it.”

Sergeant Ackley beamed. “I surely worked hard enough on it,” he said.

“How did you figure it out?” Captain Carmichael asked.

“Just concentration and persistence,” Sergeant Ackley replied modestly.

“Simple as that?” the captain asked.

“Hardly simple,” the sergeant protested. “I walked the floor for two nights. I didn’t sleep a wink for forty-eight hours.”

“Well,” Captain Carmichael announced, “some officers could have walked the floor for a month and still couldn’t have got it. I have an idea this training you’ve been getting with Leith has developed your deductive powers. I don’t mind telling you that the chief was very much impressed. You’re going to hear more of it, sergeant.”

Sergeant Ackley ripped the end off a cigar. His eyes were glowing.

“Thanks,” he said.

In the car ahead, Lester Leith found driving, with the broad brim of his sombrero cutting off his view on either side, sufficiently difficult to force him to concentrate his entire attention on the road ahead. Not once did he turn to look behind. He, perforce, paid no attention to the other traffic on the boulevard.

Chapter V.

The Green-Eyed Monster.

Io Wahine was sprawled in velvety-skinned comfort on the chaise longue. Her features were relaxed in the effortless smile which is the natural heritage of the Hawaiian. Pearly teeth showed between red lips. The clear olive skin of her face served as a fitting background for the smoky hue of her limpid eyes. There was something completely at rest about her, a relaxation which spoke of perfect muscular co-ordination, reminiscent of a cat sprawled on a hearth.

Job Wolganheimer, on the other hand, was the exact antithesis. So thin that he seemed to be nothing but skin and bones, bowlegged, restlesseyed, he paced the floor, walked over to the window, looked down into the alley, walked over to the wall, stared moodily at a picture, went to the kitchen, had a drink of water, and called raspingly over his shoulder:

“How about it, Io? Want a drink?”

“No, thanks,” she said, in lazy tones of perfect contentment.

Wolganheimer walked back into the living rooms, snapping his fingers nervously. For the tenth time within the last twenty minutes, he looked at his watch.

“Bonneguard was to be here,” he said, “ten minutes ago. I wonder what’s keeping him.”

Io Wahine saw no reason for trying to answer the question.

Wolganheimer again walked over to the window, looked down into the alley.

“When I tell Bonneguard what I’ve got on Bradercrust, there’s going to be a big blowoff,” he said. “You and I probably will have to lie low for a while. It’s going to make a stink.”

“What do you have on Bradercrust?” she asked, with a curiosity which was so indolent that, when he didn’t answer the question, she merely yawned, stretched her superb figure, raised her arms and clasped her hands behind her head.

The doorbell rang.

Wolganheimer jumped as though a shot had been fired, whirled and raced toward the door.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Seven Sinister Sombreros»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Seven Sinister Sombreros» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Seven Sinister Sombreros» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.