“Harry came back to the London flat one night with Joe and said he was his nephew,” she explained coolly to Hester.

“It was true. For the night, he was a relation,” Joe said.

“And he was going next day. But he was very interested in music. We have a Hi-Fi in London,” Moira went on. “It’s too loud for the country.”

“I don’t even know what Hi-Fi is,” Hester said.

“You have a kind of horse-trough filled with sand and a box of knobs for the gramophone records,” Joe explained. “You hear every sound, even the tears rolling down the conductor’s cheeks. After you have Hi-Fi there is nothing else, absolutely nothing, but to go out and hear the concert when it’s played. But Harry likes this Hi-Fi noise. He plays records every day. Carried away on the space-ship to the music of the spheres, he explains to me. But he’s not carried away. He’s anchored on the sofa. Why do I have this Hi-Fi, perhaps you ask? With my connections, how can I ask my friends to hear a clockwork gramophone?”

“You see, Harry spent the first few days just listening to Hi-Fi,” Moira said, beginning to smile. “It seemed rude to interrupt him.”

Joe scowled. “Then I begin to tell him, you’d like to go soon, Harry. This very evening, he says, but the banks are closed, can you cash a cheque? A very small cheque, Harry, I tell him. A very small cheque indeed. How much is it worth to me to get rid of Harry? Ten pounds, perhaps, I think, but he makes it twenty. He is about to go. Suddenly it is raining. His coat is at the cleaner’s, he tells me, and he’ll have to stay the night after all. So what happens?” He stopped, scowling at Hester.

Hester smiled sadly. She wanted to leave, but it was hard not to hear everything about Harry.

“What happens?” he repeated. “At three that morning I am playing Donegal Poker. I go to bed at six with Donegal Poker insomnia. It is true I have won, but all I have won is my own cheque back from Harry. The next day I have to see accountants, managers, lawyers – it is very difficult for me. But Harry is not difficult. He is happy. He is writing a poem. We mustn’t disturb him, Moira says.”

“Poetry is a wonderful occupation,” Moira said angrily.

“The next afternoon, at five, he goes – with another cheque, because the banks are closed again. At eleven he is back, with friends he wants to hear our Hi-Fi. Take the Hi-Fi, Harry, I say. Take it and go.”

“The next morning I find him telephoning dealers, asking what they will give for a second-hand Hi-Fi. Now I want to get angry. Moira stops me. He’s a poet she says.”

“He is a poet,” Moira said softly. Hester looked at her with the astonished glance of a woman acknowledging an enemy. A flash of contempt for Moira’s forty years crossed her face like a beam of light.

“He is a poet in words. That is now of no importance. I am a poet of money. Words! We have too many words. Word poets talk all the time of love and death. People fall in love and they die, and no amount of poetic advice has ever helped them to do either of those things more successfully. They are interested in love for a few years, and later they are afraid of death. But they are always interested in money. Everyone, everywhere is interested in money all the time. There’s never been an age when people agreed so heartily to be interested all at once in the same thing. They’re crazy about money, even if it’s only to buy a bar of chocolate or a diamond necklace. This is how I am a poet in money. I’m not tied down to pearls and cigars. I have imagination and daring. I’m not frightened by six figures. I make beautiful combinations with banks and factories. I have just been buying more cinemas,” he added reflectively.

“A poor poem, at the moment,” Moira commented.

“I was telling you about Harry,” Joe said in a sombre voice. “In the end I say we are going to the country for a week. We lock up the London flat, I tell him. I am sorry, I say, but this time it’s goodbye. And what happens? He comes with us to the country here. I spend the first night in the quiet of this village playing Donegal Poker. I am lucky he doesn’t stay in London, break into the flat, steal my wife’s jewellery.”

“Which is in the bank,” Moira said, yawning.

“Because he is a bad man. I warn you, Hester, he is bad. He’s the kind of man who would pawn his grandmother’s crutches to buy a drink for a friend.”

“Thank you for the tea,” Hester said in a furious voice.

“You’re angry?” Moira enquired curiously. “Has Joe said something to offend you? Don’t take him seriously.”

“I don’t think it’s right to say these things about Harry,” Hester said. “You shouldn’t say them, Uncle Joe. It’s not true. Whatever Harry is, he’s honest. You just don’t understand him.”

“Have some more tea,” Moira suggested.

“I don’t understand him!” Joe repeated in amazement.

“No you don’t. He’s not one of the people who’s interested in money. He stands for something much finer than money. He doesn’t know about money, and because he doesn’t worship it as you do you think he’s no good. I agree with him. I despise money.”

“But so do I,” Joe said. “My dear child, I couldn’t agree with you more. So there’s no argument. I won’t quarrel with you. You know, Hester, I’m not even rich. I owe much, Inland Revenue is after me, and I leave the rest to Harry.”

He looked at her anxiously. She didn’t smile.

“I’m a ruined man, Hester,” he said pathetically. “Television and the weather – I can’t survive them. I’m going to Ireland on Friday to buy some new cinemas, try to earn a little something.”

“You told me you were going to Ireland to get away from Harry,” Moira said maliciously. She glanced at Hester, seeming to absorb and reflect again the knowledge that Hester was wearing last year’s clothes. “I don’t say I believe you. I should have thought the way you feel about Harry, something far away like India would have suited you better. A soupgon more cream, Hester?”

“My wife doesn’t like Harry,” Joe explained. “She is only afraid to dislike him because he is a poet. We are both worried when we think we think of nothing but money. So we have Hi-Fi, and go to opera.”

“Opera. Wagner is divine,” Moira agreed, yawning.

Joe’s jowls sagged a little at the mention of Wagner.

“Verdi, Bizet, now Bizet is something,” he said quickly. “Do they have Verdi and Bizet in India?” he demanded.

No one knew.

“I thought Bizet was very O.K. Then I saw that first thing of his. Enough. I didn’t like it. But the Russians – Eugene Onegin? Do they have Eugene Onegin in India or Australia? Europe is all I want.”

“Is Ireland Europe?” Moira asked languidly. She rose and glanced quickly in the mirror. Her complexion was the cosmetician’s dream come true, as rich and soft as marshmallow, just tinged with Turkish delight.

“How are you going?” Hester asked coldly. She hadn’t been deceived by the talk of opera. Joe hated Harry, and she wanted to leave his house.

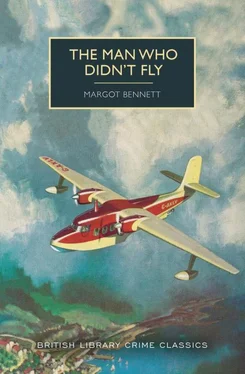

“I’m flying,” he said. “I’ve chartered a plane and it has three empty seats. Do you happen to know anyone who would like to share it?”

HESTER walked home through the woods without looking at them. There was a world inside her head, and it was filled with a dozen versions of a defenceless Harry overborne by enemies. England was a country that didn’t appreciate its poets until they were playwrights, or dead, but even so she was astonished by the malice which her father, Uncle Joe, and Morgan had shown towards Harry. She knew that what they hated was not Harry, but their own failure to be as he was. Harry, in his innocence, was like a clear pool in which they saw their own pretences. She couldn’t endure any more attacks on Harry. She hesitated at the gate, and then turned away from the house and walked through the woods until she came to the ruined chapel.

Читать дальше