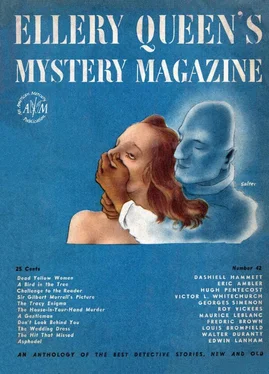

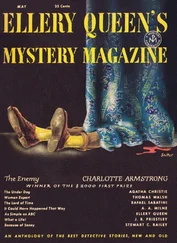

Эрик Эмблер - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Эрик Эмблер - Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1947, Издательство: The American Mercury, Жанр: Классический детектив, Детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947

- Автор:

- Издательство:The American Mercury

- Жанр:

- Год:1947

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

That was the worst part of it, Edward reflected. He couldn’t stop thinking about it, even though he told himself that he ought to let the matter drop before he caused a barrier more serious than her secretiveness, than the four husbands, the four dead men.

He wondered now if he should have consulted a psychiatrist. It was unhealthy the way his thoughts had returned to those four men, and he had realized that it could not go on so indefinitely. But there were things he had to know and she should have told him. This other fellow, this in-between man, he had a name, and Edward felt he ought to know it.

One day he had been reading Pope from a handsomely bound library set that Elaine had put in the shelves and he came across a marked passage in a translation from Homer that said:

“And rest at last where souls unbodied dwell ,

In ever-flow’ring meads of asphodel.”

He read it aloud, asked, “You mark it, dear?”

“I?” Elaine had raised her eyebrows. “Of course not. Why should I?”

“I wonder who did,” Edward had said. “Asphodel. That’s the flower of the dead that blooms in hell. Nice line, too... where souls unbodied dwell, In ever flow’ring meads of asphodel. Where did the book come from?”

She had moved her shoulders uneasily, her eyes turning aside in evasion. Edward had persisted, “Whom did it belong to? Rice?”

“I believe so.” She had risen. “Time for bed, Edward.”

“Yes, all right. In a moment.”

But Edward had closed the book on his knees and sat staring into the fire. It was an odd passage to have marked, where souls unbodied dwell, and he wondered if Rice’s hand had made the pencil lines in the margin, if Rice had known about the three before him, if those three had been unbodied, but present and accounted for, as all four were for Edward. It was a beautiful, exotic word, asphodel, and Edward had thought that it somehow suited Elaine. Then he had wondered if he had called her that, this fellow Rice. To himself he might have called her Asphodel.

It was that morbid line of thought again, running through his mind as he sat posing in the studio. That night he had tried to stop it by throwing the book to the floor. But sleepless in bed he had thought of Rice and found him as absorbing as the fellow in between, whose name he did not know. He’d been a newspaperman on the Coast, Edward knew, and rather small potatoes, at that. An obvious mismatch for Elaine. But the man had liked poetry and he had found that passage and marked it. Asphodel, the pale lily of the dead.

The word repeated itself in Edward’s brain now as he sat looking at the bronze faun, and his lips moved silently in saying it. Was it only three days since he had seen the letter in her handbag? It seemed like weeks.

They had been about to go out for the evening, and as Edward opened the door the telephone had rung. Elaine had answered it, and after a moment he heard her clear voice saying, “Wait, I’ll get a pencil and jot it down.”

She had returned. “Do you have a pencil, Edward?”

“No. Afraid not.”

“I must have one.” She had opened her handbag, found a pencil, and dropped the bag on a refectory table.

Edward had waited impatiently in the foyer. It had been one of those idle moments when the mind pauses and the eye strays, and for a long time he had looked at the sheet of green paper that had fallen from her bag before he bent over to pick it up. It was because of the letterhead, Greenvale Cemetery , that his eyes had dropped to the lines of type below. It was a bill for the upkeep of a cemetery plot in a small town fifty miles from New York. He had hardly digested the fact when Elaine returned.

“Edward,” she had said, and her voice had broken off as she stared at the green paper in his hand. Then she had taken it from his fingers and tucked it in her bag, saying, “Shall we go?”

Descending in the elevator he had noticed that her eyes were shining and her face was flushed. She did not explain, and he had asked no questions, but he had thought, which one was it? Was it Rice or George or Larry or the other one, the one in between, whose memory was kept verdant in the Greenvale Cemetery.

During dinner that night he had tortured himself. He should have asked her outright, he had thought. After all, an explanation was due. He hadn’t pried. The letter had fallen to the floor, and he had naturally picked it up. But since he’d seen it, the least she could do was explain. He had to know which one it was.

As he lit cigarettes for them both on the way home in a taxi she had said lightly, “Edward, do you know I haven’t a commission? Not a single commission.”

“Oh, one will come along.”

“Not that. I mean for the first time since we were married I’m free. I haven’t a commission and I can do what I want. Edward, I’d like to do a head of you.”

Edward had been pleased. Her work had always been something apart, and he had been happy to be included in it, flattered that she should wish to do a bust of him.

“So, darling, let’s get up early,” she had said. “I want to get started on it first thing in the morning.”

It was fascinating, he thought now to see the sureness of her strong fingers molding the clay. She was a small woman, with a high-bridged nose that gave her thin face a sharp, flat perspective in profile, and her gray eyes held a light of watchful perception, like a cat’s. It was surprising, he thought, that her work should be so powerful, almost monumental.

The first day he had been enthusiastic as he watched his own head taking shape in the clay in massive, oversize planes. But the following morning something had gone wrong and she had mashed his clay nose, saying, “That’s all for today, Edward.” She had left the studio and he had not seen her again until dinner, when she talked little. He had been depressed and kept thinking of the letter from the Greenvale Cemetery.

As they were having coffee he had asked her bluntly, “Elaine, why the bill from a cemetery?”

Her eyes had met his for an instant, with a gleam of anger. “Edward, what do you mean by going through my pocketbook? Really, I’ve had enough of your prying.”

“It fell out on the floor when you took the pencil. I simply picked it up. Darling, I wasn’t prying into your affairs.”

“Very well. Then let’s not talk about it.”

“But I did see it, Elaine, and I’m curious. Why the cemetery plot? No reason why you can’t tell me about it, is there?”

“But I won’t tell you, Edward. I simply will not encourage your morbid curiosity. We’ve talked this all out and you promised not to pry.”

“We also said no secrets. Remember?”

She had risen to her feet and the angry shine of her eyes was almost hatred, surely contempt. She had said sharply, “Edward, we can’t go on like this. Really, I think you’d better do something about it. See somebody. How about that man Betty West goes to, Doctor Lewis? Why don’t you see him, Edward?”

He had banged his fist on the table. “I don’t need a psychiatrist. That’s a pretty shabby means of evasion, Elaine. That’s no answer to a direct question.”

“You need medical attention more than you realize, Edward,” she had said quietly. “And I don’t intend to answer any questions put like that. Good night.”

Now Edward frowned at the faun, rigidly holding his pose. It was the bottle of Scotch he had opened last night, after she left, that had given him the headache. He had known then, while drinking the Scotch, as he was sure now, that there was nothing wrong with his mind, that there was nothing morbid about his curiosity. Perhaps it was unhealthy to keep thinking about those three and the other one, the in-between one, but if she would talk about them openly and honestly he’d be able to get them out of his head. And that letter from the cemetery ought to be explained. He had the right to an explanation.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine. Vol. 9, No. 42, May 1947» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.