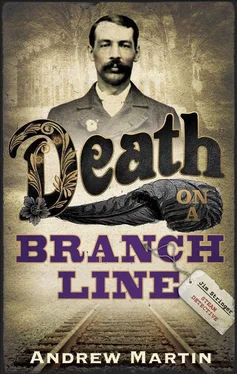

Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death on a Branch line

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death on a Branch line: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death on a Branch line»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death on a Branch line — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death on a Branch line», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But for all that, the row with the wife was just as strong in my thoughts. It was hardly our first one. We had small ones regularly about the late hours I was called on to work. It all boiled down to the demands the Chief placed upon me, which the wife did not understand. The Chief’s wife seemed to stand anything; he lived his whole life in a man’s world.

‘I’m sorry I packed you off,’ I called to her through the trees, after twenty minutes or so.

‘You did not pack me off,’ she called back, crashing through some ferns. ‘I chose to leave.’

‘Well, I’m sorry that I made you choose to leave then,’ I said. ‘I just think it was a bit of a distraction to start telling him that you couldn’t use a railway timetable.’

‘Credit me with some intelligence, please. I wanted to keep him talking,’ said the wife.

‘Funny way of going about it,’ I said, ‘… by talking yourself.’

‘I had the idea that I was on the verge of a discovery.’

‘What?’

‘Oh, get back in your box,’ she said. ‘And take that flipping cap off.’

‘I will not,’ I said. Indicating a path, I stopped and said to the wife, ‘After you.’

‘Stow it,’ she snapped back, but she led off in the direction I’d shown her.

The woods gave out and a cricket ground came into view. The pavilion put me in mind of a white wooden railway station. At one end of the ground stood three tall poplars, and they might have been giant wickets, only they stood some way beyond the boundary. The wicket was a strip of especially bright green light.

I followed the wife along the lane that bounded the pitch, which turned out to connect with the second village green of Adenwold. We walked past the silent churchyard, the shops and cottages, and began drifting along the hedge-tunnel, where the bees whirred as they worked the great green walls. The neglected ladder remained in place, looking very forlorn, for the hedge could grow and it could not.

I heard what might have been a motor-car in the far distance, and stopped to try and make out the sound, but the wife kept walking, drawing her straw hat against the left-hand hedge, and taking down her hair, which you would have thought a complicated business but which she accomplished with two impatient strokes of her right hand. When she took her hair down, that always meant she was going off into her own world.

As we trudged on past the station yard, the hour chimes from the church floated up, the bell toiling with great effort, as though climbing a steep hill to the maximum number: twelve o’clock. Hugh Lambert had forty-four hours left; his brother possibly fewer still. The train that might bring the Chief was due in twenty-seven minutes’ time. I called up to the wife: ‘I’m off to meet the train in. I’ll come up, presently.’

But she just walked on towards The Angel.

I crossed the station yard, and walked up onto the ‘up’, where a smell of white-wash, combined with the great heat of the day, made me feel faint. The whole of the platform seemed to tilt for a moment and the signal box lurched.

The signalman was up there, leaning on his balcony. Eddie by name. He appeared to be grinning down at the porter, Woodcock, who sat on the fancy bench smoking, and looking at a pot of white-wash set down by the platform edge. He’d started renewing the white edging, but had got only about a third of the way along. I took my top-coat off, and draped it over the fence that separated the ‘up’ platform from the station yard.

‘You had enough of this place, mate?’ said Woodcock. ‘Are you making off?’

I made no reply to that, but removed the Lambert papers from my coat pocket, and sat down by the fence to read them: The dog is everything to the boy, and accompanies him at all times. He uses it a good deal for rabbiting, of which he knew I disapproved, but Mervyn Handley has an innate diplomacy, which always prevented him from speaking about his pursuit of rabbits in my presence. I would often think that he would have been the perfect son for father to have. Aged eight, I fell off the cob, and had concussion of the brain; later, I perfected the art of going backwards on a pony. I doubt that Mervyn would have required a leading rein for year after year, as I did. The boy has taught himself shooting, but I’m sure that he ‘shoulders’ a gun (if that be the correct expression) in the right manner, and I’m sure that, given the chance, he would be the ‘hard man to hounds’ that Ponder and I were always supposed to become. He could never be categorised as a booby or a mollycoddle, even by a man so keen to employ those epithets as father. I do not mean to be patronising about the boy. There is more to him than pluck and a keen eye. He is intelligent, and who is to say that he does not have the brains to take a first at Cambridge as Ponder did? This, of course, will remain undetermined.

Approaching the bottom of the page, the writing became scrawl and I shuffled the pages once more, but I found that I couldn’t break in again: every new page seemed equally crabbed. I sat back, and closed my eyes.

When I opened them, the clock on the platform said 12.27 dead on, and I felt my face stiff with sunburn. I didn’t like the idea of having slept in Woodcock’s presence. He remained smoking on the bench just as before, but as I lifted my coat off the wicket fence, I checked through its pockets for warrant card, pocket book and watch, and found them all present.

‘Any news of the 12.27, mate?’ I called over to Woodcock. ‘It’s not running late, is it?’

‘Don’t know,’ he said, ‘and I’m not your mate.’

It had been a daft question. How could he know? The telegraph line was down.

‘You leaving without your missus?’ he said.

‘Meeting a pal,’ I said.

‘Another journalist?’ he said.

‘Yes, since you ask.’

He didn’t believe me.

Did John Lambert’s timetable work somehow connect him with these blokes at the station? I looked from Woodcock to the paint pot.

‘It’s almost too hot to work today,’ said Woodcock, ‘and I never thought I’d hear myself say that. Anyone who knows me would be amazed to hear me coming out with those words.’

I watched him blow smoke.

‘In a state of shock they would be,’ he said.

‘Where’s your governor?’ I enquired, and it seemed to me possible in that instant that Woodcock and the signalman had killed and eaten station master Hardy. But Woodcock looked along the platform towards the small sidings and the goods yard. As he did so, I heard the bark of a small engine from that direction.

The station master was on the warehouse platform, swivelling in the driving seat of a steam crane, the steam and smoke rising up from his rear — from the little motor that was located behind him like a bustle. He fitted so snugly into the seat of the crane that he looked like a steam-powered man. A good-sized crate was attached by canvas belts to the jib of the crane, and station master Hardy was loading it onto a flat-bedded wagon that had been drawn up by the warehouse. The wagon would be taken away on the next pick-up goods to come through Adenwold. That would be on Monday.

How many Lamberts would be dead by then?

I wondered again about station master Hardy’s miniature soldiers. Did he move them about at intervals like chess pieces, the movement on one side requiring movement on the other? How did a miniature soldier die? How was that event signified? If you were a boy, you just knocked the soldier over — and you usually didn’t stop at one.

The man Gifford… Perhaps I ought to have directed him towards Hardy, who might have an interest in scale models in general. Then again, did model soldiers come in the same scale as model trains? This was the connection that John Lambert was required to make: the connection between soldiers and railways. And who had charged him with the task? Surely the government: the War Office. In which case, who employed his seeming opponent Captain Usher? They couldn’t both be in the service of the state; couldn’t both be on the side of right.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

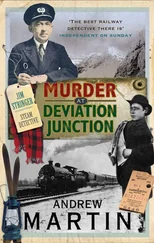

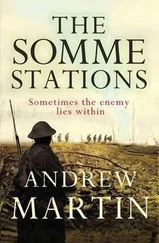

Похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death on a Branch line» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.