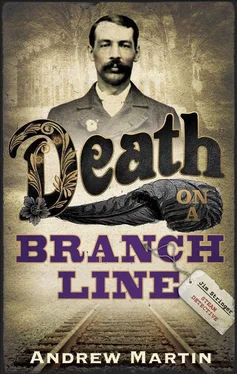

Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death on a Branch line

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death on a Branch line: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death on a Branch line»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death on a Branch line — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death on a Branch line», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘You’d have had that earlier if you’d carried our bags,’ I said.

‘Well then,’ said Woodcock, looking down at the coin, ‘I’m glad I didn’t bother. This is all for the bloody Hall, of course. Why do you want to know?’

And it came to me that I might put him off with a lie.

‘You asked me last night if I was a journalist,’ I said. ‘As a matter of fact I am. I’m hunting up a bit of background for an article on the hanging of Hugh Lambert.’

‘What paper?’

‘Various,’ I said. ‘I’m with a news agency.’

He eyed me.

‘Is there anything you’d like to tell me about Hugh Lambert?’ I ran on. ‘Or John, come to that?’

‘There is not,’ he said.

A consignment note was tucked into the leather belt that held the lid of the hamper down. I caught it up before Woodcock could stop me. The delivery came from York, and was marked: ‘Lambert, The Gardener’s Cottage, The Hall, Adenwold, Yorks.’

I looked across the station yard towards the triangular green. The dapper man in field boots was still gazing about. He was a stranger to Adenwold, that much was obvious.

‘Lift the lid,’ I asked the porter, pointing at the hamper.

He made no move.

‘Irregular, that would be,’ he said. ‘Mr Hardy might not like it.’

He nodded towards the urinal, where station master Hardy was making water, the top of his head just visible over the wooden screen.

‘You don’t care a fuck for what he thinks,’ I said.

‘That’s true enough,’ the porter said. ‘Give me a bob and I’ll do it.’

He was a mercenary little bugger. I handed him the coin; he unbuckled the strap and pushed the lid open. ‘Aye,’ he said, looking down, ‘… seems about right.’

Inside the hamper were perhaps fifty railway timetables, all in a jumble. At the top was one of the Great Eastern’s, with a drawing of one of that company’s pretty 2-4-2 engines running along by the sea-side. But in the main, the basket held the highly detailed working timetables that came without decorated covers and were meant for use by railwaymen only.

Woodcock kicked the lid of the basket shut.

‘Timetables,’ he said. ‘Bloke’s mad on ’em.’

As he spoke, I watched the dapper man in field boots striding across the green. He moved with purpose, and I knew I’d better get after him.

‘When’ll they be carried to the Hall?’ I asked Woodcock, indicating the timetables.

‘Carter’ll take ’em up presently.’

‘When?’

‘When it suits him — don’t bloody ask me.’

‘Who’s that bloke just got down?’ I asked Woodcock, pointing towards the man in field boots.

‘Search me.’

‘Well, don’t worry, mate,’ I said, keeping one eye on the bloke. ‘Everything considered, you’ve been surprisingly helpful.’

‘That’s me all over,’ said Woodcock.

‘I’m obliged to you,’ I said.

‘I’m more surprising than I am helpful,’ he said as he made off, ‘so look out.’

The man in field boots was walking amid the cawing of rooks towards the two lanes on the opposite side of the green from the one leading to The Angel. Of this pair, he was aiming towards the lane furthest away from the station, which was bounded by two towering hedges. I made after him, but lagging back a little way.

The hedges made two high walls of green with brambles and flowers entangled within. A ladder stood propped against one of the hedges, and it looked tiny — only went half-way up. But it was a good-sized ladder in fact. The only sounds in the hedge-tunnel were our footfalls and the birdsong, and I thought: It must be very obvious to this bloke that he’s being followed. But he did not appear to have noticed by the time we came into the open again.

Here was a clearing, and another triangular green, this one better kept than the first and with — for all the heat — greener grass. A market cross stood in the centre of it. A terrace of cottages ran along one edge of the green. They looked pretty in the sunshine, and quite deserted. Their owners were having a holiday from them, and they were having a holiday from their owners. A row of three shops ran along another side: a baker’s, a saddle-maker’s and a tobacconist and confectioner’s, this last with the sun kept off by window posters for Rowntrees Cocoa and Player’s Navy Cut that looked as though they belonged in York and not out here in the wilds. Only the baker’s looked to be open, and there was a good smell coming out of it: hot and sweet, to go with the dizzying smell of the hundreds of flowers blooming all around.

The shops stood opposite to me, the terrace to the left. On the right was Adenwold parish church, which was contained within the half-ruined skeleton of a much larger church, and covered over with ivy. In the graveyard were little enclosures made of thick hedges, like natural rooms, and inside these were clusters of graves — whole families of the dead. Alongside the graveyard was a grand pink house. This must be the vicarage, and I was sure it had claimed the vicar who’d just left the station.

The lately-arrived man in field boots was now examining a finger-post that pointed towards a narrow road running away to the left of the baker’s. I came up behind him and read: ‘TO THE HALL’.

‘You’re for the Hall?’ I asked the man.

He wheeled about, but he hardly looked at me. Rather, he seemed to be looking into the far distance, and I had the idea that he might have learnt that gaze in Africa. But he also had London written all over him — expensive education and five hundred pounds a year. He gave the shortest of nods. He was for the Hall. At this, I gave him my name but again kept back my profession. The man put down his bags and shook my hand, but didn’t introduce himself. His eyes were exactly the same colour as the sky.

He was a tough-looking bloke, and if one of those bags of his held a gun — which seemed to me more than likely — and if he was on his way to shoot John Lambert, I would not be able to stop him by force. All I could do was try to put him off by saying what I knew.

‘There’s a man staying at the gardener’s cottage which is connected to the Hall,’ I said. ‘His name’s John Lambert and I believe him to be in danger of…’

‘Of what?’ asked the man, and it was not sharp, but in the manner of a polite enquiry.

‘In mortal danger,’ I said.

There was a silence. Or rather the air was filled with the sound of bees.

‘How do you know?’ the man eventually asked.

‘He said as much. I spoke to him yesterday.’

The man put down his bags.

‘Did you seek him out, or just come upon him?’

‘I’m here on holiday,’ I said. ‘I was out strolling with my wife, and I just came upon him.’

The man put his hands behind his back, and placed his legs wider apart.

‘Did you not recommend that he summon the police?’

He’d forced my hand.

‘I am the police,’ I said, and I showed him my warrant card, saying, ‘Do you mind my asking your business at the Hall?’

But, still with his hands behind his back, he put a question of his own:

‘You’re here on holiday, you say?’

‘I am.’

‘Who’s your officer commanding?’

And that was sharp.

‘That don’t signify,’ I said, feeling like a lout. ‘I’ve asked about your business at the Hall.’

‘I have an association with John Lambert,’ said the man. ‘I am… a confidant of his. The poor fellow is considerably agitated at present.’

It struck me as I spoke that John Lambert might be a mental case, and that this might be his doctor. He picked up his bags, and said, ‘You can be assured that my visit is in Mr Lambert’s own best interests.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

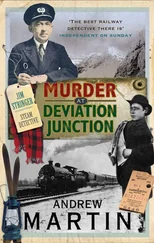

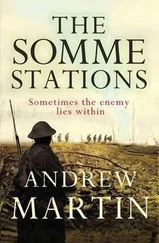

Похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death on a Branch line» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.