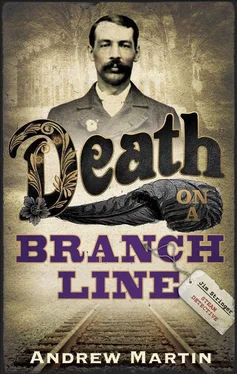

Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Andrew Martin - Death on a Branch line» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Death on a Branch line

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Death on a Branch line: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Death on a Branch line»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Death on a Branch line — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Death on a Branch line», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘What is your profession?’

He stopped, and half-turned towards me, saying, ‘I fill notebooks, Mr Stringer.’

Chapter Thirteen

We walked fast through the woods. The darkness was drawing down, but still the heat hung heavy in the wide, tree-made tunnels. In the light of John Lambert’s warning, the woods looked different. The trees either side of us were monsters — great spiders with even their highest branches swooping right down to the ground.

‘Do you believe it now?’ I asked the wife.

‘I think there’s something in it all,’ she said.

Whether she believed it or not, she would be leaving Adenwold in the morning, I would make sure of that. One murder had happened and another was coming, or at least an attempt, and I would have to put myself in the way of it. It struck me again that I ought to get the Chief over to Adenwold first thing in the morning. I knew he was generally in the office of a Saturday.

We came out of the trees and we were at Mervyn’s set-up, which was more than ever like the scene of an explosion in the woods. As far as I could make out, the lad had gone, and taken all the dead rabbits with him. We walked on, and struck the railway track, which we followed a little way, walking under the telegraph wires. The wife was ahead of me, stumbling now and then on the track ballast.

‘Hold on,’ I said, ‘we’re heading the wrong way.’

But she’d come to a stop in any case. The wires from the pole before us were down, and lay by the side of the tracks, all forlorn like a dead octopus. They ran on as normal from the next pole along, but of course one break was all that was needed.

Was this to prepare the way for the killers?

Or were they already in the village?

This doing would cut off the station’s telegraph office — very likely the only one in the village — from all points west, and it was odds-on the line would be cut the other way, too. How could I contact the Chief now, short of taking a train out in the morning? But if I did that, I would miss the ones coming in. And would the trains run? It was possible to operate a branch line without telegraphic connections, but special arrangements had to be put in hand.

The wife stood silent, with arms folded as she kicked at one of the stray wires. She said, ‘They have ordnance maps of the whole country-side, you know — the travelling agents, I mean. They’re picked up from time to time, but it’s all hushed up.’

We walked on in silence through the dark woods. Every so often, there came a crashing as a bird tried to fly through the trees, and I did wish they would stop trying, for they put me in a great state of nerves.

When we gained the top of the road that rose from the centre of the village, we saw a greenish light through the windows of The Angel. I opened the front door, and we stepped into the little hallway where we had the options ‘Saloon’ or ‘Public’, or the stairs that led up to our room. There was no question but that Lydia would take the stairs. She didn’t drink, and had never set foot inside a public house, but when I asked, ‘You off up, then?’ she said ‘Not just yet’, and stepped into the public bar with me.

Was it fear or curiosity that had made her do it?

We pushed through the door, and half a dozen — no, eight — faces looked back at us.

It turned out that, whichever door you walked through, you got the saloon and the public, and that the bar — on which stood six green-shaded oil lamps — was a sort of wooden island in-between the two. The ‘public’ side was wooden walls and wooden benches. The ‘saloon’ side was a little smarter. It had the red rose wallpaper and a fish picture over the fireplace similar to the one in our room. This one showed a pike, but with no instructions and no display of hooks. (If you wanted to catch a pike, you could work out how to do it yourself.) All the windows were open, and a warm breeze occasionally wandered through from the ‘public’ to the ‘saloon’ side. Mr Hardy, the fat station master, stood alone at the bar on the ‘public’ side, and there were a couple of agricultural fellows talking and smoking at a table behind him. The two arrivals-by-train — the bicyclist and the man from Norwood — sat in the saloon side, and each had a small round table to himself. The man from Norwood had a pipe on the go, and was reading documents. The bicyclist was eating a pie — the Yorkshire pie, I guessed. Every now and again, he would lay down his knife and fork and give a loud sigh. After a while, it came to me that this might be connected to the fact that Mr Handley the landlord, sitting on a high stool on the saloon side, was addressing him. He did so again now, in a very deep, drunken voice, an underwater sort of voice like a deaf man’s, and I couldn’t make it out, but the bicyclist sighed again and said, ‘It certainly cannot be ridden in its present condition — not with the inner tube holed. The wheel would zig-zag intolerably.’

His machine was evidently punctured. Like most who take to biking he was middle class — might have been a university product. As I watched, Mr Handley was served a pint in a pewter by his wife. It must have gone hard with her that he wasn’t paying.

Mrs Handley smiled — still cautious, but I had a persuasion that she was warming to us. I ordered a pint of bitter for myself and the lemonade for the wife, and Mrs Handley seemed quite chuffed at this. Her husband being a man for strong waters only, and her boy not liking lemons, I supposed that she was glad to find a taker for her home-made brew. She poured the lemonade and then said to me: ‘We have John Smith’s bitter, and Thompson’s ale. The Thompson’s is a little stronger.’

‘Oh, my husband knows all about that,’ the wife cut in, and I thought with excitement: Now she’s definitely nervous. Unpredictable things happened when the wife became stirred-up.

Mr Handley made some further remark to the bicyclist. I couldn’t understand a word he said, yet the bicyclist seemed to have no trouble in doing so.

‘Cycling is certainly beneficial in that way,’ he said, in reply to Mr Handley. ‘It is said to promote a general activity in the liver,’ he added, at which he gave a pitying look to Handley, as if to say, ‘But your liver has enough on as it is.’

He then stood up and quit the bar.

I asked for John Smith’s, and plunged in haphazard as Mrs Handley passed me the pint.

‘Almost everyone hereabouts has… well, gone.’

She folded her arms and eyed me for a while.

‘Moffat’s here,’ she said, ‘down on the East Green. He’s the baker.’

‘Why hasn’t he gone?’

‘He doesn’t like Scarborough, I suppose.’

‘Can’t credit that,’ said the wife, and she grinned, whereas Mrs Handley did not. Or not quite, anyhow.

‘Caroline and Augusta are here,’ said Mrs Handley.

‘Who are they?’

‘They’re the old ladies in the almshouses.’

‘Oh,’ I said, ‘the elderly parties. We saw them. Why haven’t they gone?’

‘Well, they’re too old. They have those houses at a peppercorn rent. They’re supposed to be infirm. They can hardly go off… enjoying themselves.’

And here she did give a quick smile. She was continuing to eye me carefully, however.

‘Who runs the Scarborough outing?’ asked the wife.

‘Christmas Club,’ said Mrs Handley. ‘You see, the Christmas Club here has nothing really to do with Christmas. You put in your money, and you have three days in Scarborough.’

‘Don’t you get a turkey at Christmas?’ I said.

‘You get a chicken,’ Mrs Handley said after a while. ‘But people like the Scarborough jaunt. It’s a village tradition.’

‘I suppose nobody from the Hall’s gone, have they?’ I asked Mrs Handley.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Death on a Branch line» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Death on a Branch line» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.