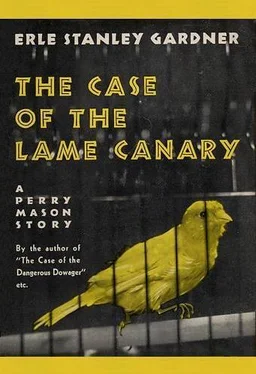

Erle Gardner - The Case of the Lame Canary

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Erle Gardner - The Case of the Lame Canary» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1937, Издательство: William Morrow, Жанр: Классический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Case of the Lame Canary

- Автор:

- Издательство:William Morrow

- Жанр:

- Год:1937

- Город:New York

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Case of the Lame Canary: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Case of the Lame Canary»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Case of the Lame Canary — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Case of the Lame Canary», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Yes,” Cuff said, his expression bland. “You see, I’d heard that the district attorney’s investigators had taken charge of the canary, and I deduced that could mean only one thing. Thanks to your clever deductive reasoning, Driscoll knew the jig was up, and told me the circumstances frankly, where he might otherwise have tried to conceal them.”

“How did you know about Weyman as a witness?” Mason asked.

Cuff laughed. “He told his wife, and his wife told Stella Anderson, and she keeps a secret like a sieve holds water. I felt I could call him unexpectedly and make a better impression than if I’d talked with him and introduced him as a willing witness.”

Mason nodded, lit a cigarette and said, “How do you suppose Rosalind’s going to feel when she learns that Driscoll tried to divert suspicion from himself by involving Rita Swaine?”

“You surely don’t think he did that?” Cuff asked.

“Yes, he did exactly that.”

Cuff thought for a moment, then said, “One thing you may be overlooking, Mr. Mason: Before this inquest started, the district attorney was preparing extradition proceedings against both Rita Swaine and Rosalind Prescott. As matters now stand, he will proceed to extradite Rita Swaine. He can’t extradite Rosalind Prescott — not in the face of this evidence.”

“And you think that’s a good thing?” Mason asked.

“I think so, yes.”

“For whom?”

“For Rosalind Prescott, primarily.”

“How about Miss Swaine?” Mason inquired.

“Miss Swaine,” Cuff told him, “will have to take care of herself — with your very able assistance.”

Mason nodded, said, “I gathered as much. You know, Cuff, there’s just one disadvantage about having your client stage this cards-on-the-table act.”

“What’s that?” Cuff asked.

“God help him if he’s lying,” Mason said grimly.

Chapter eleven

Rita Swaine sat across from Perry Mason in the visitor’s room in the county jail. A long row of heavy wire mesh divided the table into two parts. Rita sat on one side, and Mason on the other.

“Can I talk here?” she asked.

“Keep your voice low,” Mason said, “and, above all, don’t get excited. People are watching us. Make your manner casual. No matter what you tell me, shake your head once or twice emphatically, as though denying your guilt. Now, go ahead and tell me the truth.”

“Rosalind killed him,” she said.

“How do you know? Did she say so?”

“No, not in so many words. Oh, it’s awful. She’s my own sister, and now she’s turned against me. She and Jimmy Driscoll did it and she’s willing to have Jimmy make me the goat because she loves him so much she can’t bear the thought of anything happening to him, and he’s pushing it all over on me just to save his own skin.”

“How do you know they killed him?” Mason asked.

“Because,” she said, “they did. Walter came in and caught Jimmy there, and Jimmy shot him.”

“Go ahead,” Mason told her, his voice a low, rumbling monotone. “Tell me what you know. But shake your head first — that’s it.”

“Rossy called me over the telephone, said something awful had happened and asked me to go over to her house right away. I told her I couldn’t go right at that moment. So then she told me to go down to the pay station in the drug store and call a certain number. She did that because she didn’t want to take chances on having the clerk at the switchboard hear what we were talking about.”

“All right,” Mason said, “you went to the drug store and called her. Where was she?”

“She was at the airport then. She told me that Jimmy had been there in the house with her; that he’d taken her in his arms and made passionate love to her; that there’d been an auto accident out front and the police had made Jimmy give them his name and address and that he’d be called on as a witness. She said that Jimmy had given her a gun right after the accident and before he’d run into the police; that she’d dropped the gun down in back of a drawer in the desk in the solarium. Then she said Jimmy had tried to leave, had run into the police, and had decided the only thing to do was to run away with her; that Mrs. Snoops had seen everything and she’d undoubtedly tell Walter.”

“So what did you do?” Mason said.

“She gave me all the details, told me that she’d left the dress she’d been wearing in the bedroom and that the canary was fluttering around the solarium.

“Well, of course, I told her I’d go over and put on an act for the benefit of Mrs. Snoops. I didn’t want to do it particularly, because I was afraid I might run into Walter. But she told me she knew absolutely Walter wouldn’t be there.”

“Did she tell you how she knew?” Mason asked.

“No.”

“So you went over there?” Mason inquired. “And then what?”

“When I went to the upstairs bedroom to change into the dress Rossy had been wearing, I found the door to Walter’s bedroom slightly ajar. I didn’t think anything of it at the moment, left my dress there, put on Rossy’s,went down to the solarium, caught the canary, and did my stuff where Mrs. Snoops could get an eyeful. Then I went back upstairs to change my dress again. I went into the bathroom to wash my hands, and got a shock. There were bloodstains on the wash bowl — not stains of pure blood, but places where drops of bloody water had dried on the porcelain, leaving little pinkish stains, and in some places the drops hadn’t dried.

“So I pushed open the door, looked in Walter’s bedroom, and there was Walter, lying on his bed, on his back, his arms outstretched, his vest unbuttoned, and blood flowing from bullet wounds. I stood there on the threshold and screamed. Then, after a moment, I cried out, ‘Walter, what’s the matter?’ and ran across to the bed, knelt by his side and put my hands on his shoulders.

“I knew right away that he was dead.”

She paused, breathing heavily through dilated nostrils. Her lips quivered.

“Go ahead,” Mason told her. “Give me the rest of it.”

“Honestly, Mr. Mason, I don’t know what made me do the thing I did next. At first I was so shocked and horrified I could hardly breathe. And then, all of a sudden, I seemed to adjust myself in relation to what it would mean to me and to Rossy—”

“Never mind the psychology,” Mason said. “What did you do? ”

“I thought about that letter Jimmy had written. I knew that Walter had planned to file suit against Jimmy and I knew what it would mean to Rossy if they should search the body, find that letter and—”

“What did you do? ” Mason interrupted.

“I opened his inner pocket, took out his wallet and looked for the letter.”

“Did you find it?”

“Yes.”

“What did you do with it?”

“Folded it and put it in the top of my stocking.”

“You were wearing Rosalind’s dress at the time?”

“No, I’d taken off the dress.”

“Were you wearing a slip?”

“Not then. I put one on later.”

“How long was it before you took that letter out of your stocking?”

“After I’d got downstairs.”

“What did you do with it?”

“Burnt it in the fireplace.”

“How did you bum it?”

“Why,” she said, “I touched a match to it. How does anyone ever bum things?”

“That isn’t what I mean. What did you do with the ashes?”

“Why, left them in the fireplace, of course.”

“Did you take a poker or a stick or anything and break them up?”

“No, I set fire to the letter, saw it was burning, and then tossed it into the fireplace. It flamed up all at once and singed my hair a little.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Case of the Lame Canary»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Case of the Lame Canary» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Case of the Lame Canary» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.