“I don’t know,” she said calmly.

“Look at it,” Sampson said, “examine it. Take it in your hands. Look it over and then tell us whether it is your bag.”

“I tell you I don’t know.”

“Do you mean you can’t tell whether this is your bag or whether this is not your bag?”

“That’s right.”

“You were carrying a bag last night, weren’t you?”

“I don’t know.”

“Do you mean to say that you don’t know whether you were carrying a bag in your hand when you went to call on Mr. Austin Cullens?”

“That’s right — I don’t even know that I went to call on Mr. Austin Cullens.”

“You don’t know that? ”

“No,” she said placidly. “As a matter of fact, I’ve been trying to cudgel my brains ever since I regained consciousness. I can remember yesterday morning, that is, I guess it was yesterday.” She turned to Perry Mason and said, “This is Tuesday, isn’t it, Mr. Mason?”

He nodded. “Yes,” she said, “it was yesterday morning. I can remember yesterday morning. I can remember everything that happened. I can remember receiving the keys to my brother’s car. I remember going and getting the car. I can remember putting it in the garage. I can remember waiting in the shoe department of a department store. I remember, later on, being accused of shoplifting. I remember having lunch with Mr. Mason... And I can’t remember one single thing that happened after I left that store.”

“Oh,” Sampson said, sneering, “you’re going to pull that old stuff, that your mind’s a blank, are you?”

Mason said, “That isn’t a question, Sampson, that’s an argument.”

“Well, suppose it is an argument?”

Dr. Gifford said, “I think Mr. Mason is right. Within reasonable limits, you may question my patient, but you certainly aren’t going to argue with her, or attempt to browbeat her.”

“That old alibi has whiskers on it a foot long,” Sergeant Holcomb said sneeringly.

Dr. Gifford said, “As a matter of fact, in case you gentlemen are interested, it quite frequently happens that following a concussion, there’s a complete lapse of memory covering a period of from hours to sometimes days prior to the shock. Occasionally, with the passing of time, that memory slowly returns.”

“How much time, would you say, would have to elapse in this case,” Sampson asked sarcastically, “before Mrs. Breel would recover her memory?”

“I don’t know,” Dr. Gifford said. “It depends upon a variety of factors which are outside of my consideration.”

“I’ll say it does,” Sampson said disgustedly.

Mason said, “Let me ask you, Dr. Gifford, is there anything particularly unusual in this lapse of memory in connection with a concussion history such as we have in the present case?”

“Nothing whatever,” Dr. Gifford said.

Sampson pulled the knitting from the bag. “Look here, Mrs. Breel,” he said. “Can’t you recognize your own knitting?”

She said, “May I see it, please?”

Sampson extended it to her. She looked it over critically and said, “Rather a nice job of knitting. Whoever did this was very expert.”

“You knit, don’t you?” Sampson asked.

“Yes.”

“Do you consider yourself an expert knitter?”

“I am very good,” she said.

“Do you recognize that as your knitting?”

“No.”

“Would you say that it was not your knitting?”

“No.”

“Would you say that if you were knitting a blue garment, of that sort, you would knit it in about that manner?”

“I think any expert knitter would.”

“That isn’t answering my question. Would you knit in that way?”

“Yes, I think so.”

“And you won’t say that is your knitting?”

“No. I don’t remember ever having seen it before.”

Sampson exchanged an exasperated glance with Sergeant Holcomb, then dug down into the bag and said, “All right, Mrs. Breel, I’m going to show you something else and see if this refreshes your recollection.” He unwrapped the paper from the diamonds. “Did you ever see this jewelry before?”

“I’m sure I couldn’t tell you,” she said.

“You can’t tell us?”

“No. I cannot remember ever having seen it before. But, until I completely recover my memory, I wouldn’t care to make a positive statement.”

“Oh, no, certainly not,” Sampson said sarcastically. “You want to give us every assistance in the world, don’t you?”

Dr. Gifford said, “May I remind you once more, Mr. Sampson, that this woman has suffered a very severe nerve shock?”

Sampson said sarcastically, “She seems to need a mental guardian, all right. It’s too bad about her being such a babe in the woods.”

Mason said, “As Mrs. Breel’s lawyer, I am going to ask you gentlemen to complete this examination as quickly as is humanly possible. Are there any further questions you wish to ask of Mrs. Breel?”

“Yes,” Sergeant Holcomb said. “Mrs. Breel, you went out there to Austin Cullens’ house, didn’t you?”

“I don’t remember.”

“You knew where Austin Cullens lived, didn’t you?”

“I can’t even remember that.”

“His name’s on the address book at your brother’s office, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so, yes... Come to think of it, I believe I’ve mailed a few letters to him at his address... out on St. Rupert Boulevard, I believe.”

“That’s right. Now, you went out there last night, at about what time?”

“I tell you that I don’t know that I went out there.”

“You entered that house,” Sergeant Holcomb said, “and you entered it surreptitiously. You unscrewed one of the electric light globes and placed a copper penny inside the socket so that in case Cullens should come home and press the light switch, the copper coin would short-circuit the wires and burn out every fuse on the circuit, didn’t you?”

“I’m sure I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said.

“You don’t remember doing that?”

“Most certainly not. I tell you the last thing I remember was shaking hands with Mr. Mason in the department store.”

“Then,” Holcomb said triumphantly, “if you can’t remember where you were or what you did, you can’t positively swear that you didn’t take a thirty-eight caliber revolver and shoot Mr. Austin Cullens last night about seven-thirty, can you?”

“Of course not,” she said. “I can’t tell you what I did, and it follows that I can’t tell you what I didn’t. I may have assassinated the President. I may have wrecked a train. I may have forged a check. I might have got married. I don’t know what I did or what I didn’t do.”

“Then you won’t deny that you killed Austin Cullens, will you?”

“I most certainly have no recollection of having killed Austin Cullens.”

“But you won’t deny that you did it?”

“I can’t remember having done so.”

“But you may have done so.”

“That,” she said, “is another matter. I’m certain that I can’t tell what might have happened. I only know that I never killed anyone before yesterday afternoon, and I have no reason to believe that yesterday afternoon was any different from any other afternoon in my life.”

“You were worried about your brother, weren’t you?”

“No more so than I have been on other occasions.”

“You knew he’d gone out to get drunk?”

“Yes. I surmised that.”

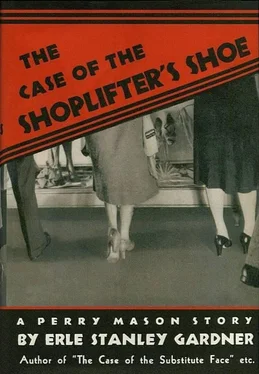

“Let me ask you this,” Larry Sampson said. “Do you remember doing any shoplifting?”

She hesitated a moment, then said, “Yes.”

“You do?”

“Yes.”

“Where? When?”

“Yesterday afternoon, or rather yesterday noon, just before I met Mr. Mason.”

Читать дальше