She joined me by the hearth. ‘Silly girl never remembers the screen,’ she said, moving it in front of the grate. She perched upon the edge of her chair so that her feet might reach the floor, and stared at me, the wine, the butler, with barely concealed distaste. Her eyes were fringed with thick black lashes, and very dark. Despite her ill-humour, they were quite captivating.

Bagby poured me a glass of claret. I wondered how he kept his gloves and stockings so crisp and white. I suspected by giving all the troublesome jobs to his men. Well, it was his prerogative, I supposed.

Mrs Fairwood held a hand over her own glass, and told him to close the terrace doors. ‘Then leave us.’ Bagby did as he was ordered. ‘Ghastly man,’ she muttered, without explaining why. But then I’d yet to hear her speak well of anyone. We might all be reduced to a two-word insult by Mrs Fairwood. Silly girl. Ghastly man. Frightful rake.

The sounds of the yard were now muffled, and the pungent stink had been locked outside, leaving only a faint whiff on the air. The clock on the mantelpiece ticked quietly. I gulped down most of the wine, and filled the glass again to the brim.

Mrs Fairwood seemed reluctant to begin, so I prompted her. ‘Well then, madam. You believe you are Mr Aislabie’s lost daughter?’

She pulled off her gloves and sighed heavily. ‘Yes, Mr Hawkins, I do. And may God help me to endure it.’

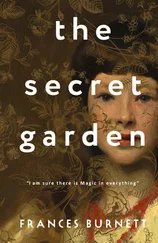

Mrs Fairwood was raised in a small village on the Lincolnshire coast, the nearest town a day’s ride away. There was money – a good deal of it – and a grand house with servants. She called her childhood ‘quiet’ – I thought it sounded lonely, trailing the empty rooms, filling the silence with books. She had no siblings, but she was close to her father, who recognised her appetite for knowledge, and encouraged it.

‘And your mother?’

‘Devout.’ Her teeth trapped the last letter. She didn’t appreciate the interruption. I drank my wine and settled back, shoulders relaxing in the deep embrace of the armchair. The heat from the fire burned upon my cheek.

‘When I was twenty-one, my father decided we should spend the summer in Lincoln with his sister. There was talk of finding a husband. I had dissuaded him many times before. I was content at home.’ Her eyes flickered to the shelves behind me. ‘My father insisted. He said it was time that I lived in the world, not just in my books.’ Her fingers clenched together in her lap.

‘When was this?’

‘Eight years ago.’

1720. So she was twenty-nine. That would match Elizabeth Aislabie’s age, if she survived the fire.

‘At the last moment my mother took to her bed: a nervous attack. I thought my father would abandon the trip, but we set off the next day without her. My aunt would act as chaperone once we reached Lincoln.’

She poured herself a thimbleful of wine. ‘I do not drink.’

‘Evidently.’

Her dark eyes lifted to mine. ‘How dull I must seem to you. My drab little story.’

I did not find her dull. Petulant, yes, and chilly, but not dull. In truth her story had drawn me in: the earnest timbre of her voice; the measured way she chose her words. I had grown accustomed to Kitty, who would speak a half dozen sentences in one breath, who spoke not only with words but with her hands, her eyes, her whole body. Mrs Fairwood moved no more than was needed, spoke no more than was needed, her voice clipped and precise.

She sipped the wine. ‘Is this a good claret?’

‘The best.’

She rolled the stem of the glass between her fingers. ‘This glass, too. These chairs.’

Yes, it was all very fine – and hers to enjoy for ever if she could persuade the world she was Aislabie’s lost child. This story might be nothing more than a fortune hunter’s yarn. I placed my glass on the table. Mrs Fairwood had a closed countenance, but I had made a great deal of money at the gaming tables, reading truth and lies on my opponents’ faces. I leaned forward, watching closely.

‘To my surprise, I enjoyed my stay in Lincoln,’ she said, returning to her story as if by rote. ‘My aunt’s circle was small but scrupulously well selected. I had the opportunity to speak with a number of learned men upon a diverse range of topics. The great matters of our age. Theology, metaphysics, affairs of state, the very systems of the universe…’

I made a silent note never to visit Lincoln. ‘And this is what you study here, in Mr Aislabie’s library? That is your copy of Lucretius on the desk?’

She frowned at this fresh interruption. ‘It belongs to Metcalfe. You will meet him at dinner, if he can be roused.’ She leaned back and stared at the clock on the mantelpiece with the blank expression of an automaton.

I must wind her up, then. ‘Pray – continue, madam.’

‘Oh.’ She feigned surprise. ‘Forgive me, sir. I thought you must have grown tired of my story. Would you not rather discuss Lucretius? I take it you have read De Rerum Natura .’ Her lips curled into a condescending smile.

‘I think I fell asleep upon a copy once, at Oxford.’ This was not true. I had, in fact, studied the blasted thing at some length as a student. But if Mrs Fairwood wished to cast me as a japing idiot, that suited me perfectly well. Another lesson from the gaming table: better to be thought a fool than a threat. ‘Please.’

She dipped her chin in gracious assent. ‘That summer in Lincoln was a happy time. Home had become oppressive, though I only realised this once I had left. My mother never strayed far from the village, but in her later years she would not even leave the house, save for church. My father too seemed altered by the trip. He laughed more easily. It is a comfort now to think of those last days.’ She looked down. ‘He died. My father died. It came without warning. One moment he was well, and the next…’ A tear slid down her perfect cheek. She trapped it beneath her fingers, brushed it away.

‘I’m sorry.’

Eight years had passed, and still the grief lingered. I could see how naturally it fell upon the contours of her face, how familiar and constant a companion it had become. How, in fact, it had shaped her, and turned her beauty into something austere and remote. I had lost my mother when I was a child and understood that ache, that hollow yearning for a beloved parent. This much of her story, at least, was true.

She took another sip of wine. ‘I could not bear to return home without him. There was a gentleman. James Fairwood. I didn’t love him. He was thirty years my senior and… well. I did not love him. But he was kind, and asked nothing of me. I accepted his proposal.’ There was a short pause, as she wrapped herself in old, private thoughts of her loveless marriage. ‘Mr Fairwood had come recently into a fortune. We bought a large manor house near Horncastle. Five years later my husband fell ill with a fever and died. I was alone.’

I sensed a rich satisfaction in that final sentence. ‘That is young to be widowed. You must have been desolate.’ I chose the word deliberately – it was too rich an emotion for her, and I wanted to hear her denial.

She gave it at once, with some force. ‘Desolate? No indeed! The marriage had been a convenience for both of us.’ And then she froze, realising her mistake.

‘A convenience? How so?’

She was furious with herself. She had been so careful with her story, reciting her monologue with precision. No wonder she hated my questions. Nothing an actress dislikes more than interruptions from the audience. ‘We kept each other company.’

I put my glass to my lips, hardly able to conceal my amusement. Imagined James Fairwood, recently come into a fortune, searching Lincolnshire for the most cheerful companion he could find – and choosing this elegant block of ice. Hogwash. ‘There were no children?’

Читать дальше