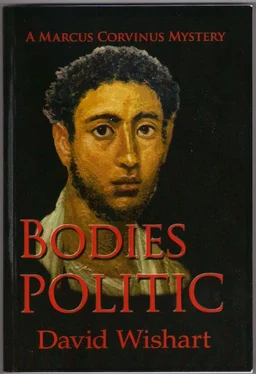

David Wishart - Bodies Politic

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «David Wishart - Bodies Politic» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Bodies Politic

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bodies Politic: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Bodies Politic»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Bodies Politic — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Bodies Politic», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I let myself be led off. Well, you had to look on the bright side. At least I’d miss the bloody recitation.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

I did, but not by much, despite the fact that I was away for a good hour and a half, which was what it took for the doctor to sponge my cuts and examine the bruise on my shoulder, and for me to wash off the mortar from the Staurian wall in Vinicius’s bath suite and change into the fresh tunic and mantle that Tynnias had brought me. Also to sink another half pint of Caecuban while all this was happening.

When I rejoined the party I was feeling almost human again. They were applauding, but not very enthusiastically, which suggested that Seneca’s poetry had been the pulp-factory-fodder that Perilla had said it was. Mind you, if I’d had to choose in advance I’d still’ve taken it in preference to being almost squashed flat by a stonemason’s cart. But then maybe I’m just getting old.

‘Marcus?’ Perilla was there, beside me. ‘How are you feeling?’

I was looking around the room; Rome’s brightest and best was right, if you kept your tongue firmly in your cheek while applying the phrase, with a generous sprinkling of four-star imperials. Not counting Vinicius I could spot three of these straight off, even if I didn’t know them personally. First, the nondescript, middle-aged guy in the plain mantle, who twitched while he talked like he had the palsy and favoured his right leg whenever he moved: Gaius’s uncle, the idiot Claudius, who the imperial family had kept under almost permanent wraps since he was born, and quite rightly so from the looks of him. The broad-striper he was talking to was smiling and nodding like he wished he was a million miles away, but at a party you can’t flatline a gabby imperial, even although he is a no-brainer who’s boring your socks off, and the poor guy was stuck for the duration. Second, Livilla, Vinicius’s wife, Gaius’s sister, about six feet to our left, against the wall behind the Marsyas statue, talking to the fat would-be star of the show who was lapping up her compliments like a cat at a cream-bowl. Livilla was fairly hefty herself, thick in the body but pretty enough in the face. Not, from reports, that there was very much going on behind those heavily-made-up eyes. To distinguish between Gaius’s youngest sister and a brick, intellectually speaking, would be a decision that went to the wire.

Third was Agrippina…

Agrippina. I’d never met her either, but I recognised her as soon as I saw her. An Imperial with a capital ‘I’, straight from the Livia mould, and that bitch I’d remember even if I made ninety. She and her sister were chalk and cheese, with Livilla being the cheese, and a full-fat one at that. There was none of her sister’s flab about Agrippina. Early twenties or not, she was bone-dry, angular and hard, more flint than chalk, and by the gods the lady had presence and she knew it. She was talking to a young man with a squeaky-clean broad-striper mantle. I suddenly thought of female spiders, and the hairs rose on my neck.

There was no sign of her husband Domitius Ahenobarbus. Him I’d’ve spotted anywhere.

‘Marcus?’

‘Hmm?’

‘I asked you a question. How are you feeling?’

‘I’m okay, lady. I told you, no bones broken. Just scratches.’ I fielded a cup of wine from a passing slave’s tray. ‘Where’s Ahenobarbus?’

‘He’s dying.’

‘ What? ’ I nearly dropped the cup.

‘Or the next thing to it.’

Well, I wouldn’t grieve for the bastard, nor would many other people. Still, it was a facer. ‘You’re sure?’

‘Absolutely. I asked Vinicius. Oh, very discreetly, but I thought you’d want to know. A combination of dropsy and alcohol. His doctors don’t think he’ll last the year.’

Bloody hell! ‘Does Agrippina know?’

‘Of course she does.’

‘Ah, Corvinus.’ It was Vinicius himself, coming up on my blind side. ‘Suitably restored?’

‘Yeah. Yeah, thanks. I’m fine.’

‘You missed a treat.’ I glanced at him suspiciously, but his face was bland. ‘Annaeus Seneca was in marvellous form. As usual. A true showman.’

‘I’m not into poetry myself, sir,’ I said. ‘Can’t tell bad from good, I’m afraid.’

‘ That can be an advantage. Certainly a blessing, in some circumstances.’ He turned to Perilla. ‘Your stepfather, now, Rufia Perilla, he was a poet. I’m sorry I was too young ever to meet him. His Metamorphoses are a lovely idea; Circe the enchantress changing men into swine is such a telling comment on the morality of our times, isn’t it?’

‘I, ah, don’t think my stepfather meant it like that.’

‘Poets can say more than they intend, or even what they know, my dear. It’s one way of telling good from bad. And speaking of your stepfather, there’s someone who’d be delighted to meet you.’ He raised his voice. ‘Anteius! Over here, please!’

The young guy talking to Agrippina said a few final words to her and came across. He was big-built, with a florid complexion and reddish hair: Northern Italian, probably, maybe even with more recent Gallic blood.

‘Gaius Anteius, Rufia Perilla and her husband Valerius Corvinus,’ Vinicius said. ‘Anteius is a fellow-poet, Perilla. A close friend of Seneca’s. He’s one of our new quaestors.’

That explained the squeaky-clean mantle. ‘Pleased to meet you,’ I said. We shook.

‘You’re in distinguished company, Anteius.’ Vinicius patted his arm. ‘Rufia Perilla is Ovid’s stepdaughter, and an excellent poet in her own right. Now if you’ll excuse me I must just go and check on the wine supplies. Glad to see you’re little the worse for your experience, Corvinus. I’ll have my carriage take you back, even so.’

‘Hey, no, that’s okay,’ I said. ‘We can manage in the litter.’

‘I insist. It’ll be waiting for you outside whenever you’re ready. In the meantime, enjoy yourselves.’ He smiled, and was gone.

‘You’re from the north?’ Perilla said to Anteius.

‘Yes. My father has estates near Mantua.’ The guy was blushing; one of nature’s ingenus. Well, the family must be rolling right enough: even these days, a Cisalpine Italian his age didn’t make the first rung on the senatorial ladder easily, not with so many youngsters from the top Roman families in contention. ‘What was he like? Your stepfather?’

‘You enjoy his work?’

‘It’s brilliant,’ he said simply. ‘I’ve read every line a hundred times. He’s even better than Virgil, and as a Mantuan myself I shouldn’t say that.’

Perilla laughed. ‘Well, he wasn’t at all like you might imagine from his poetry. A very quiet family man. If you’d met him you might have been disappointed.’

‘Oh, no! He was a genius, everyone says so. I was talking to Cornelius Gaetulicus a couple of months ago, and he said Publius Ovidius Naso was the greatest lyricist Rome had ever produced, streets ahead of Catullus. He models his own style on your stepfather, although he says he’ll never be a fraction as good.’

‘Gaetulicus?’ I said.

He stared at me. ‘The erotic poet, of course.’

‘Ah,’ I said. ‘Right. Right.’

‘He knew your stepfather, you know.’ He turned back to Perilla. ‘Not well; he was only my age when Ovid was exiled. In fact, I think he only met him twice. But he said he was the most intelligent man in Rome. Not the cleverest, but the most intelligent. And, of course, an absolutely brilliant poet. His banishment was a tragedy.’

‘Yes,’ Perilla said quietly. ‘Yes, it was.’

‘Why did Augustus do it? Do you know?’

‘Yes. But it’s a long story.’

‘Where did you -?’ I began; but I was interrupted.

‘Gaius, dear, Seneca would like a quick word.’ Agrippina. Her hand was on Anteius’s arm. ‘I’m sorry to drag him away,’ she said to me, ‘but you know these sensitive artists. Everything has to be done now.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Bodies Politic»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Bodies Politic» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Bodies Politic» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.