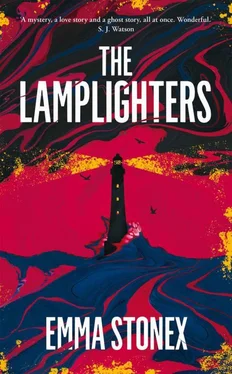

He can decipher the Maiden in the haze, a lone spike, dignified, remote. She’s fifteen nautical miles out. Keepers prefer that, he knows: not to be so close to land that you can see it from the set-off and be reminded of home.

The boy sits with his back to her – a funny way to start, Jory thinks, with your back to the thing you’re going to. He worries at a scratch on his thumb. His face looks soft and ill, uninitiated. But every seaman has to find his legs.

‘You been on a tower before, sonny?’

‘I was out at Trevose. Then down at St Catherine’s.’

‘But never a tower.’

‘No, never a tower.’

‘Got to have the stomach for it,’ says Jory. ‘Have to get along with people too, no matter what they’re like.’

‘Oh, I’ll be fine about that.’

‘Course you will. Your PK’s a good sort, that makes a difference.’

‘What about the others?’

‘Was told to watch out for the Super. But being your age roughly, no doubt you’ll get along fine.’

‘What about him?’

Jory smiles at the boy’s expression. ‘No need to look like that. Service is full of stories, not all of them true.’

The sea heaves and churns beneath them, blackly rolling, slapping and slinging; the breeze backs up, skittering across the water, making it pimple and scatter. A buffet of spray explodes at the bow and the waves grow heavy and secretively deep. When Jory was a boy and they used to catch the boat from Lymington to Yarmouth, he would peer over the railings on deck and marvel at how the sea did this quietly, without you really noticing, how the shelf dropped and the land was lost, where if you fell in it would be a hundred feet down. There would be garfish and smoothhounds: weird, bloated, glimmering shapes with soft, exploring tentacles and eyes like cloudy marbles.

The lighthouse draws near, a line becoming a post, a post becoming a finger.

‘There she is. The Maiden Rock.’

By now they can see the sea-stain around her base, the scar of violent weather accumulated by decades of rule. Though he’s done it many times, getting close to the Queen of the Lighthouses always makes Jory feel a certain way – scolded, insignificant, maybe slightly afraid. A fifty-metre column of heroic Victorian engineering, the Maiden looms palely magnificent against the horizon, a stoic bastion of seafarers’ safety.

‘She was one of the first,’ says Jory. ‘Eighteen ninety-three. Twice wrecked before they finally lit her wick. The saying goes she makes a sound when the weather hits hard, like a woman crying, where the wind gets in between the rocks.’

Details creep out of the grey – the lighthouse windows, the concrete ring of the set-off, and the narrow trail of iron rungs leading up to the access door, known as the dog steps.

‘Can they see us?’

‘By now.’

But as Jory says it, he’s searching for the figure he’d expect to see waiting down there on the set-off, the Principal Keeper in his navy uniform and peaked white cap, or the Assistant waving them in. They’ll have been watching the water since sunrise.

He eyes the cauldron around the base of the lighthouse with caution, deciding the best approach, if he’ll put the boat ahead or astern, if he’ll anchor her down or let her stay loose. Freezing water splurges across a sunken warren of rocks; when the sea fills up, the rocks disappear; when it drops, they emerge like black, glistening molars. Of all the towers it’s the Bishop, the Wolf and the Maiden that are hardest to land, and if he had to pick, he’d say the Maiden took it. Sailors’ legend had it she was built on the jaws of a fossilized sea monster. Dozens died in her construction and the reef has killed many an off-course mariner. She doesn’t like outsiders; she doesn’t welcome people.

But he’s still waiting to see a keeper or two. They’re not getting this boy away unless there’s someone on the end of the landing gear. At that point with the drop and surge he’ll be ten feet down one minute and ten up the next, and if he loses sight of it his rope’s snapping and his man’s taking a cold bath. It’s a hairy business but that’s the towers all over. To a land man the sea is a constant enough thing, but Jory knows it isn’t constant: it’s fickle and unpredictable, and it’ll get you if you let it.

‘Where are they?’

He hardly hears his mate’s yell against the gush of water.

Jory signals they’ll go around. The boy looks green. The engineer too. Jory ought to reassure them, but he isn’t quite reassured himself. In all the years he’s come to the Maiden he’s never taken the boat around the back of the tower.

The scale of the lighthouse rears up at them, sheer granite. Jory cranes his head to the entrance door, sixty feet above water, solid gunmetal and defiantly closed.

His crew holler; they call for the keepers and blow a shrill whistle. Further up, higher still, the tower tapers into the sky, and the sky, in return, glances down at their little vessel, thrown about in confusion. There’s that bird again, the one that followed them out. Wheeling, wheeling, calling a message they don’t understand. The boy leans over the side of the boat and loses his breakfast to the sea.

They rise, they fall; they wait and wait.

Jory looks up at the tower, hulked out of its own shadow, and all he can hear are the waves, the crash and spit of foam, the slurp and wash of the rocks, and all he can think of is the missing girl on the radio that he heard about that morning, and the bus stop, the empty bus stop, and the driving, relentless rain.

STRANGE AFFAIR AT A LIGHTHOUSE

The Times , Sunday, 31 December 1972

Trident House has been informed of the disappearance of three of its keepers from the Maiden Rock Lighthouse, fifteen miles southwest of Land’s End. The men have been named as Principal Keeper Arthur Black, Assistant Keeper William ‘Bill’ Walker and Supernumerary Assistant Keeper Vincent Bourne. The discovery was made by a local boatman and his crew yesterday morning when attempting to deliver a relieving keeper and bring Mr Walker to shore.

As yet there is no indication of the missing men’s whereabouts and no official statement has been made. An investigation has begun.

NINE FLOORS

The landing takes hours. A dozen men scale the dog steps with a taste on their tongues like salt and fear, their ears raw and their hands bloody and frozen.

When they reach the door, it is locked from the inside. A slab of steel built to resist crashing seas and hurricane winds must now be broken by brawn and bars.

Afterwards, one of the men gets the shakes, the bad white shakes, which is partly exhaustion and partly the worm of disquiet that has clung to him since Jory Martin’s relief boat went unmet, since Trident House told them, ‘Get out there.’

Three of them enter the tower. Inside, it is dark, and there is a musty, lived-in smell, symptomatic of the sea stations with their battened-shut windows. There’s not a lot to see in the storeroom: bulky shapes masked by the gloom, coils of rope, a lifebelt, a dinghy suspended upside down. Nothing is disturbed.

The keepers’ oilskins hang in the shadows like hooked fish. Their names are called through a manhole in the ceiling, sent spiralling up the staircase:

Arthur. Bill. Vincent. Vince, are you there? Bill?

It’s eerie how their living voices cut through silence, the silence robust, indecently loud. The men don’t expect a response. Trident told them this was search and rescue, but it is a mission for bodies. Any thoughts they had about the keepers escaping are gone. The door was locked. They’re here, somewhere, inside.

Читать дальше