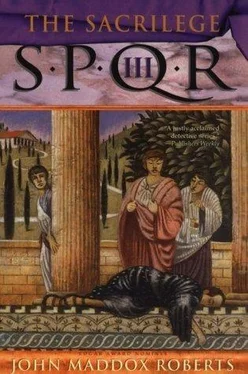

John Roberts - The Sacrilege

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Roberts - The Sacrilege» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sacrilege

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sacrilege: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sacrilege»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sacrilege — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sacrilege», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I would never claim that I had more than a fraction of Cicero's intellectual capacity, for he had the finest mind I have encountered in my long lifetime. But he had a certain blindness, an almost naive belief in the inherent capacity of aristocrats to govern.

I was born an aristocrat, and I had no illusions about my class. Aristocrats are persons who possess privilege by virtue of having inherited land. They prefer rule by the very worst of aristocrats to that by the most virtuous of commoners. They detested Pompey, not because he was a conqueror of the Alexandrine mold who might overthrow the Republic, but because he was not an aristocrat, and he led an army of the Marian type that was not composed of men of property.

At the time of which I write, my whole class was engaged in a form of mass suicide by means of political stupidity. Some rejected our best men for reasons of birth, while others, like Caesar and Clodius, curried favor with the worst elements of Roman society. Most wanted a return to their nostalgic image of what they thought the ancient Republic to have been: a place of unbelievable virtue where an aristocratic rural gentry lorded it over the peasants. What they got was our present system: a monarchy masquerading as a "purified" Republic.

Cicero was right about Celer, though. Within a year he was back among the most extreme aristocrats, opposing the land settlements for Pompey's veterans.

"It is not surprising that they dislike the idea of Pompey having a powerful private army settled near Rome," I said. "I find the idea rather upsetting myself."

"I am not so easily terrified," Cicero said. "With the Asian menace settled, there are no glorious campaigns in the offing. He will have no interest in the sort of desultory combat that Hibrida is bungling so terribly in Macedonia."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning that, for now, Pompey must stay home and devote himself to politics. The very concept is ludicrous, Pompey is a political dunce. He held most of his military commands without holding any of the offices required by the constitution. He was made Consul by force alone. He has no experience of civil administration or the real politics of the Senate. The man's never even served as quaestor! You'll be a more effective Senator than Pompey, and you've had less than a week's experience as Senator."

It was an odd sort of compliment, if compliment it was. At least I was now fairly certain that I would not be hauled into court for snooping.

I now had some people to call upon. I decided to begin at the very site of the enormity. I went to the house of Caius Julius Caesar, whose wife, we were given to believe, must be above suspicion. The house of the Pontifex Maximus was a sizable mansion, one of the few residences in the Forum, adjacent to the palace of the Vestals.

The gatekeeper let me in and conducted me through the atrium, where the household slaves went about in the gingerly fashion that bespoke uncertainty in their lives. Doubtless they were wondering which of them would stay with the master and which would accompany the divorced mistress. I noticed that the male statues still wore palls. The sun had broken through the clouds and I was conducted to the enclosed garden, where the roof-tiles still dripped musically. In a corner stood a small statue of Priapus, covered by a scarlet cloth. In front, the cloth hung from the god's outsized phallus like a ludicrous flag.

"May I help you?" I turned to see that a woman had come into the garden. I did not recognize her, but I was greatly taken by her wheat-colored hair and large gray eyes, and by the sound of her voice.

"I am Decius Caecilius Metellus the Younger," I said. "I need to speak with the Pontifex Maximus."

"He is not here at the moment," she said. "Is it a matter in which I might be of assistance?" Her grammar and diction were perfect. Her poise was elegant, her manner open and helpful without being obtrusively familiar. In a word, patrician.

"I am engaged in an investigation of the recent, ah, unpleasantness at the rites of Bona Dea in this house." She did not look pleased. "On such a matter," she said, "who has the authority to question the Pontifex Maximus?"

This was an embarrassingly penetrating question. "This is not an interrogation, my lady. I've been instructed by one of the most distinguished members of the Senate to make an informal inquiry, not to bring charges, mind you, but merely to:"

"Metellus Celer," she said.

"Eh? Ah, well, you see, you are not totally incorrect in this, but actually:" It has never been my habit to babble, but this woman had caught me completely off guard. "Who did you say you were?" I asked.

"I did not say. I am Julia." This narrowed things somewhat. She belonged to the fifty percent of gens Julia that were female.

"I knew that Caius Julius had a daughter, but I had thought she was: well, I had the impression that she was, shall we say, younger."

She kept her face patricianly impassive, but I sensed that she was laughing inwardly at my ridiculous discomfiture.

"Caius Julius is my uncle. I am Julia Minor, second daughter of Lucius Julius Caesar."

"I see. I knew you had to be one of those Julias. I mean, I should say: how did you know it was Celer?"

"You are a Caecilius Metellus and he is the husband of Clodia Pulcher."

"You have a very well-developed faculty of deduction," I said.

"Thank you. I take that as a compliment, considering its source. You are famed for that very faculty."

"I am?" I said, not sure whether to be flattered. "Yes. My uncle speaks of you often. He says you are one of the most interesting men in Rome."

"He does?" I was truly astonished. I knew Caius Julius only slightly. It had not occurred to me that he spoke of me, with or without approval.

"Oh, yes. He says there's no one like you for snooping and prying and drawing deductions. He says your skill merits classification as a branch of philosophy." I did not believe that she was deliberately flattering or gulling me. She seemed as open and honest as anyone I had ever met. Of course, no one was more aware than I of my susceptibility to attractive women.

"I have always avoided philosophy," I told her, "but who am I to dispute definitions with such a master of the rhetorical arts?"

Finally she smiled. "Exactly. Well, I am sorry that Caius Julius is not here to speak with you, but I am pleased to have met you at last." She made to leave, but I did not want her to go.

"Stay, please," I said.

"Yes?" She was a little puzzled, as was I.

"Well." I groped for words. "Perhaps you could help me. Were you here that night?"

"Only married ladies attend the rites of Bona Dea. I am not married."

"I see." I was inordinately pleased to know that she was not married. "How wonderful. I mean, I am not happy that you were not here." My words were getting tangled again.

"I didn't say I was not here, just that I did not attend the rites."

"Ah. Well, it is a rather large house."

"You're going about this all wrong, you know. I fear that you disappoint me."

"I fail to understand," I said.

"Just going into great men's houses and asking direct questions. That's no way to get to the bottom of this matter."

I was a little crestfallen. After all, who was famed for this sort of thing?

"Well, it is a little different from investigating a throat-cutting in the Subura. Could you suggest a better method?"

"Let me help you."

"You have already very kindly made that offer," I reminded her.

"I mean, let me be your helper in this investigation. I can go places you cannot."

This took me greatly aback. "Why should you want to do that?"

"Because I am intelligent, well-educated, personable and bored to a state of Medea-like madness. I've followed your career for years by way of gossip among women and table discussion among my father and his brother and their friends. It is just the sort of activity I feel drawn to. I can go places you cannot. Let me help you." In true patrician fashion she demanded this as her right, but I could detect a pleading tone in her voice.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sacrilege»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sacrilege» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sacrilege» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.