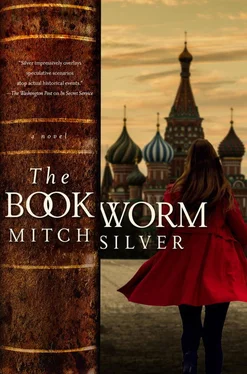

Mitch Silver

THE BOOKWORM

A Novel

To Claiborne, for believing in me.

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.

—Edmund Burke

Prologue

Villers-devant-Orval, Occupied Belgium

August 1940

The monk walked out of the cool woods from the French side of the road. On the tall man’s back, weighing him down, was the sort of rucksack the Dominicans use, fraying almost to the point of tearing where the canvas straps crossed his shoulders. He walked with a slight limp and carried a poplar walking stick that had seen years of hard use.

The grizzled man of the cloth looked back once and then set foot on the gravel road pilgrims had trod for centuries. The large wooden door of the abbey at Orval loomed ahead in the torpid summer twilight, and he made for it. A hundred and fifty years ago this was the cloister’s side entrance, but that was before the French revolutionaries burned down most of the original abbey in 1793.

The traveler withdrew his letter of introduction from the Monsignor of Liège and, using the head of his walking stick, banged on the heavy oak door. An onlooker standing back in the forest with binoculars would have observed a member of the friary come to the door and, having been given the letter, usher the visitor within.

Once inside, he was greeted warmly by the brethren at their evening meal. Though not of their order, he was invited to break bread with them and, later, was given a place to say his devotions and spend the night before traveling on.

But their guest wouldn’t be spending the night. Instead, a little after three in the morning, he slipped down to the abbey library where the medieval manuscripts were kept, dusty tomes that represented the labors of hundreds of the faithful over the eons. Placing his rucksack on the cold stone floor, he pulled on a pair of cotton gloves. Then he took out a flashlight and passed the beam over the bookshelves until he found what he was looking for.

Were any of the monks, unable to sleep, to wander down to the library now, what would they make of such a visitor? First, he used his hands to make a little more room on the shelf by sliding an illuminated thirteenth century Book of Job over from its centuries-long resting place. Then, from his sack, he carefully lifted the heavy cowhide-and-parchment volume he’d brought and slid it onto the shelf.

He took a little atomizer a woman might use to perfume herself. With it he carefully sprayed fine dust onto the book, the volume next to it, and all the nearby manuscripts—even the shelf itself. Returning the empty sprayer to his sack and dropping the gloves and the light in after it, he took up his walking stick and made his way, as quietly as he could, out of the abbey.

There was no moon to silhouette the tall man against the trees as he hurried back, without sign of a limp, up the road to the woods. Once there, he tapped on a tree trunk with his stick and was gratified to hear the same tapped-out signal played back to him. Five minutes later, standing in the clearing with the woman who had been his lookout, he took off the false beard.

So ended the first great Allied victory of World War II.

Chapter 1

Moscow, Russia

Monday

In a vast Stalin-era granite box several kilometers north of the capital’s outer ring road, Larissa Mendelova Klimt checked her cell phone one last time—nothing—before packing up the box for the return leg of her “daily commute.” Her routine never varied: pick up the yashchik in the morning, walk it along two rows of the Osobyi Arkhiv and then three rows over. Unlock the door to her carrel and set the box of old papers down on the desk. Turn on the light. Be seated. At night, pick up the box, lock up, and walk her burden back to its parking place with the other wartime files on the archive’s shelf.

She was feeling pretty good about herself. Other people went away for the summer, enjoyed the weather, swam at the seaside or in a lake, maybe. But Lara the Good Girl worked right here while Russia’s brief summer came and went. Unencumbered by her teaching load, she had waded through the captured Nazi documents in the box like an explorer. No, a cosmonaut—she was the Yuri Gagarin of academics, soaring through the unknown.

Take that day when she found two of the daily logs stuck together. Two not terribly significant days in May 1942, recorded down to the last, absurd detail by one of Hitler’s secretaries at the time, probably Johanna Wolf. Even as she carefully unstuck May 15 from May 16, she realized no Russian eyes had ever seen the page underneath; no Russian fingers had ever touched it. Of 150 million people, only Lara knew that Hitler had visited Wewelsburg to promote a cadre of SS officers at Himmler’s castle there before returning the same evening to Berlin by special train for a briefing on the Crimean offensive driving toward Baku. Okay, it was nothing special. Trivial, even. But it was all hers.

She knew what her friends called her: knižnyj červ. The “bookworm.” All they could see was the huge iron door of the Russian State Military Archive that closed behind her in the morning, never the enlightenment to be found within the heavily guarded Special, or Osobyi , section inside.

For the past eleven weeks, she had been doing exactly what she wanted to do. She spent nearly every waking minute plowing through the yellowed pages in this single box in the vast climate-controlled archive. Or else hunched over one of the preserved ’40s-era Dictaphone machines in the Listening Room twenty meters down the hall, as the voices of Hitler, Himmler, and Bormann dictated letters and summarized staff meetings on the hundreds of recordings liberated from the Führerbunker.

Even so, Lara had her reasons for being euphoric. She could tick off at least five of them on her fingers, starting with her thumb: with this last page, she had the whole dusty job of reading and translating behind her for another year. Index finger: she had her big definitive book, her Origins of the Great Patriotic War , all but written on the desk in front of her. Middle finger: Viktor was finally served with the divorce papers and she could move on with her life. Ring finger: Over the summer she had been named to fill the vacant chair in her department and would teach her initial class tomorrow as the country’s first full professor of geopolitical history. And pinkie: She had planned this summer’s work with her usual care, and had been rewarded by arriving at the last page of the Chronologies on September 8, the final allotted day. She had calculated it perfectly, which just went to prove how weird the newly minted Lukoil Professor of Geohistory Larissa Mendelova Klimt—Lara to her friends—really was.

Still, as she gazed out the big, grimy window at the handful of people hurrying along the pedestrian walk of the Leningradskoye shosse on their way home and then down at the notes she’d tapped out on her iPad, she could feel the same old niggling doubt creeping back in. Is it worth it? Is this any way to spend a life, shutting yourself away in a musty archive?

Viktor certainly didn’t think so. One time she’d read him something she’d written and he’d given that little deprecating snort of his. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. What difference does it make?”

Читать дальше