Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catilina's riddle

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catilina's riddle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catilina's riddle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Catilina's riddle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catilina's riddle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'I suppose not. But just before we left, you accused him outright of being responsible for Nemo, too. You said you could tell he was lying. You said you had proof!'

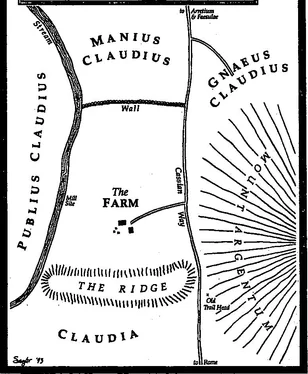

'A final bluff, a last effort to convince myself that he knows nothing at all about either of the bodies appearing on the farm. No, Gnaeus is not our tormentor. He killed Forfex, true, and for that I pray that Nemesis will punish him. Forfex somehow came to be in our well, with his head missing -1 give you credit for remembering the birthmark when I did not, and I confess to doubting you wrongly. But between the crude interment of Forfex's body and its decapitation and appearance in the well, someone else had a hand.'

'But who, Papa?'

'I don't know. Without some further crisis, we may never know.'

I could see by the look on his face that this was not good enough for Meto. Nor was it satisfactory for me, but the years had given me more patience. 'I still say we should bring charges against him,' said Meto.

'It's not worth bothering Volumenus. You've seen how long it's taking him to get a judgment on our water dispute with Publius Claudius. What is the point of bringing a suit where we have no evidence at all?'

'But we do have evidence!'

'A headless corpse with a birthmark? The testimony of a goatherd who could never be compelled to testify against his master? The complete denial of the charge by Gnaeus Claudius? The testimony of an old, senile farm slave who thinks he might have heard a splash and might have glimpsed a shadow one night when he got up to pass water? No, Meto, we have no evidence at all Granted, we might be able to bribe a jury, which is one way of winning a lawsuit in Rome when you have no case, but my heart would not be in it. I don't believe that Gnaeus Claudius was responsible.'

'But, Papa, someone must have done it. We have to find out who!'

'Patience, Meto,' I counselled wearily, and wondered if I should counsel resignation also, knowing all too well that many mysteries are never resolved. Men go on living anyway, in ignorance and fear, and though they may call their state of puzzlement intolerable, they seem able to tolerate it nonetheless, as long as their hearts keep beating.

Aratus gave me counsel on the purification of the well. Hardly a priest, he seemed nonetheless to take a practical view of the matter, and he had seen others purify wells polluted by rodents and rabbits, if not dead slaves. He thought it significant that Forfex had been properly buried, at least for a slave, before his remains were disturbed. This meant there was a good chance that Forfex's lemur had been put to rest before he was disinterred. If so, the lemur might have clung to the more familiar site of the waterfall on the mountainside, rather than follow the desecrated and beheaded corpse onto unknown soil. The arguments seemed to ring true with the slaves, who accordingly relinquished their newfound terror of the well. Whether Aratus himself believed the arguments he put forth I did not know, but I was grateful for their pragmatic effect and for his politic handling of the situation.

There remained the literal pollution of the well, for while a lemur might or might not have been involved, there was no doubt that a bloated corpse had been in contact with the water and had tainted it. A man or beast could grow sick and even die from dnnking such water. Aratus believed that the well would replenish and purify itself, given time, and meanwhile recommended that we drop heated stones into the well, to make the water boil and steam. This seemed to me like cauterizing a wound with a hot iron and made no sense in connection with a well, but I reluctantly took his advice. In the meantime, we had some water that had been stored in urns, and the stream was not completely dry. Still, there were dry days ahead.

Much of our hay for the winter had been blighted. We ran a grave risk of running short of water. I began to realize, with great uneasiness, that if another such disaster struck, I might be compelled to sell the farm. For a rich man, a farm in the country is a diversion, and if it loses money the loss is merely the cost of the diversion. But for me there was no fortune back in the city; the farm was the enterprise on which I had staked my future. Its success was essential; its failure would ruin me. That summer it seemed to me that the gods themselves were conspiring to rob me of what Lucius Claudius in his generosity had given me, and Cicero with his cleverness had secured for me by law.

Each day, Aratus fed a bit of well water to one of the farm animals, usually a kid. It did not kill them, but it did loosen their bowels and cause them to vomit. The water remained undrinkable.

I persevered with the building of the mill on the stream. Aratus had the slaves tear down a little unused shed to provide building stones and beams. Day by day the vision in my mind began to take shape. My old friend Lucius would have been surprised and proud, I thought.

I anticipated a visit from Catilina, or perhaps from Marcus Caelius, but for the rest of Quinctilis and well into the month of Sextilis I was undisturbed. In the meantime I posted slaves to act as watchmen each night, relieving each other in shifts, like soldiers in a camp. Whether this was the cause or not, we received no more rude surprises in the form of headless bodies. There was another unsettling event, however.

It was the just after the Ides of Sextilis, almost a month after our return from Rome. The day had been unusually busy. We had reached a critical pass in the construction of the mill; the gears would not mesh, though I had measured and remeasured the proportions and worked out all the calculations beforehand. Also, a thunderstorm had blown over us during the night, bringing no rain but scattering broken branches and other debris all over the property; the men had a full day's work cleaning up the mess. As the long summer afternoon dwindled to twilight, I at last had found time to rest for a moment in my study, when Aratus appeared at the door.

'I didn't want to disturb you before, because I thought it might pass, but as he's getting worse, I suppose I should tell you now,' he said.

'What are you talking about?'

'Clementus. He's ill — very ill, it appears. His complaints began this morning, but as they seemed to come and go, and as he appeared to be in no great distress, I saw no reason to bother you with it. But he's grown worse through the day. I think he might die.'

I followed Aratus to the little lean-to by the stable where Clementus slept at night and as often napped in the daytime. The old slave lay in the straw on his side, clutching his knees to his chest He moaned quietly. His cheeks were flushed, but his lips were slightly blue. A slave woman hovered over him, dabbing his race from time to time with a damp cloth. At intervals he was seized by a shuddering spasm, drew even more tighdy into a ball, and then slowly relaxed with a pathetic whimper.

'What's wrong with him?' I whispered.

'I'm not sure,' said Aratus. 'He was vomiting earlier. Now he can't seem to swallow, and when he tries to speak his words come out slurred.'

'Do any of the others share the same complaints?' I asked, thinking that a plague on the farm would be the final calamity.

'No. It may simply be because he's old.' Aratus lowered his voice. 'Such storms as we had last night are often harbingers of death to people of his age.'

As we watched, Clementus convulsed and stiffened. He opened his eyes and peered up at us with an expression more of puzzlement than pain. He parted his lips and released a long, rasping moan. After a moment the woman attending him reached out and touched his brow with trembling fingers. His eyes remained unnaturally open. The woman drew back her hand and crushed her knuckles to her lips. Clementus was dead.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catilina's riddle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.