Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catilina's riddle

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catilina's riddle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catilina's riddle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Catilina's riddle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catilina's riddle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

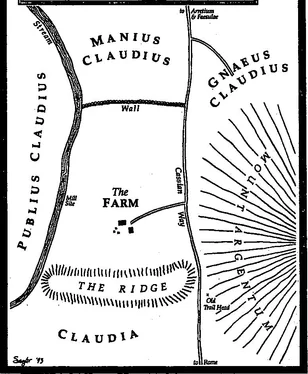

'Why must it take so long?' I complained. 'When the Claudii challenged my inheritance of the farm, that was surely a more complicated matter, but Cicero managed to have the case settled in a matter of days, not months or years.'

The corner ofVolumenus's mouth twitched slightly. "Then perhaps you would prefer to have Cicero handle all your legal affairs,' he said wryly. 'Oh, or is he too busy for that? Really, I'm doing all I can. Yes, if I happened to be one of the most powerful politicians in Rome,

then I'm sure I could arrange for the courts to expedite this matter, but I'm only an honest advocate—' 'I understand.'

'No, really, if you think you can get the mighty Cicero to take over this case, you're more than welcome—'

"That was a special favour. If you tell me that you're doing all you can—'

'Oh, but Cicero could do more, I'm sure, and better, and more quickly—'

I eventually managed to smooth his ruffled feathers before I left. I stepped back onto the street feeling not so much dissatisfied with his efforts as reminded of just how great a debt I owed to Cicero. Without his assistance and his powerful connections, the question of my inheritance, if not settled against me outright, could easily have been held up in the courts for years while I stayed in Rome and watched my beard turn grey.

On the evening of our seventh day in Rome we packed for the trip home, and set out early the next morning.

We arrived at the farm late in the afternoon, stiff and dusty. Diana leaped from the wagon at once and ran from pen to pen to give a hug and kiss to her favourite lambs and kids. Meto, his energy pent up all day, hiked at once to the ridgetop. Bethesda set about seeing how much damage the household slaves had done in her absence, and then, having perfunctorily scolded them, went to her jewellery box in our bedroom and deposited her new acquisitions.

I withdrew to my study and consulted with Aratus over what had transpired in my absence, which was little enough. The stream had dwindled even more, which he assured me was normal for the season. 'I would hardly bother to mention it,' he said, 'except that there might be a problem with the well…'

"What sort of problem?' I asked.

'The taste of the water is off. I noticed yesterday. Perhaps a cat managed to squeeze through the iron grate, or perhaps some burrowing animal dug through the wall of the shaft, fell into the water and drowned.'

'You mean there's a dead animal in the well?'

'I suspect as much. The taste of the water, as I said—'

'What have you done about it?'

From the way he tilted his head back I could tell I was speaking too harshly. 'The first thing to do in such a case is to lift off the grate, lower a bucket or a hook, and try to lift out the carcass. Dead bodies float, after all—' 'Did you do this?'

'I did. But we were unable to lift anything. At one point the hook became trapped. It took two men to pull it free. It may be that some stones have become dislodged. It could even be that a considerable portion of the wall has fallen in. If that is the case, the foul taste could have been introduced when the dislodgment took place — a burrowing animal may have been crushed or drowned, you see. If the damage is extensive — and that any damage at all has occurred is only a supposition — this could be rather serious. Major repairs to the well would prevent it from being used, and with the stream running so low…'

'How will we know whether it's damaged or not?'

'Someone will have to go down into the well.'

'Why wasn't this done yesterday? Or this morning? Meanwhile, the dead ferret or weasel or whatever just keeps rotting away, poisoning the water.'

He folded his hands and lowered his eyes. 'Yesterday, by the time our efforts to use the hook had failed, it was too dark to send anyone down into the shaft. This morning there were storm clouds approaching from the west, and it seemed to me that it was more important to bring the bales of hay from the north field into the barn, to prevent them from getting wet'

"There were bales of hay sitting outside? I thought all the hay had been brought in already.'

'It had, Master, but a few days ago I ordered the men to take the hay back out into the sun. The bales that were not lost to the blight may yet succumb, but this might be prevented by exposing the hay to the hot sunlight.'

I shook my head, dubious of his judgment once again. 'And did it rain this morning?'

He twisted his mouth. 'No. But the clouds were quite dark and threatening, and we did hear thunder nearby. Even if the slaves had not been occupied with the hay, I would have hesitated to send a man down into the well with a storm threatening, considering the danger. I know how you value your slaves, Master, and I would not squander them.'

'Very well,' I said glumly. 'Is there still time to send someone down into the well before it gets dark?'

'I was about to do that when you arrived, Master.'

I went out to the well with Aratus, where a group of slaves was already gathered. They had made a kind of harness out of rope and had tied it to a much longer rope. One of the men would put himself into the harness while the others lowered him down.

Meto joined us, smiling and red-cheeked from his climb up to the ridge and back. When I explained what was happening, he immediately volunteered to go down into the well himself.

'No, Meto.'

'But why not, Papa? I'm the perfect size, I'm agile and I'm not heavy.'

'Don't be foolish, Meto.'

'But, Papa, I think it would be interesting.'

'Meto, don't be ridiculous.' I lowered my voice. 'It's far too dangerous. I wouldn't even consider allowing you to do it. That's—' I caught myself. I had almost said; 'That's what the slaves are for,' then realized how the words would strike his ears.

Then, in the next instant, I realized how the sentiment struck my own ears. Had I really grown so callous towards the men I owned? I had inherited a farm; along with it, had I also inherited the contemptuous attitudes of slave owners like Publius Claudius or dead Cato? Use a human tool until it breaks, says Cato in his book, and then discard it for a new one. I had always despised men like Crassus, who attached no value at all to the lives of slaves, only to their utility. And yet, I thought, give a man a farm and watch him turn into a little Cato; give him mines and property and sailing ships and he becomes a little Crassus, no doubt I had turned away from Cicero precisely because it seemed to me that he had become the very thing he had once despised. But perhaps such a course is inevitable in life — wealth necessarily makes a man greedy, success makes him vain, and even the least measure of power makes him careless of others. Could I say I was any different?

These thoughts flashed through my head like a bolt of lightning. ‘You can't go down into the well, Meto, because I'm going down myself' The words surprised me almost as much as they did Meto.

'Oh, Papa, now who's being foolish?' he protested. 'I should go. I'm so much younger and more supple.' The slaves, meanwhile, looked at us in frank astonishment.

Aratus laid a hand on each of our shoulders and took us aside. 'Master, I would advise you against doing such a thing. Much too dangerous. That's what the slaves are for. If you take on such a task, you'll only confuse them.'

"The slaves are here to do as I tell them, or in my absence, as Meto tells them,' I corrected him. 'And while I'm down in the well, it's Meto who will make sure that you oversee them properly, Aratus.'

He grimaced. 'Master, if you were to be hurt — may the gods forbid such a tragedy! — the slaves would be liable for terrible punishments. For their sake, I ask you to let one of them perform this task.'

'No, Aratus, I've made up my mind. Don't contradict me again. Now, how does this harness fit?'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catilina's riddle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.