Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Saylor - Catilina's riddle» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Исторический детектив, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Catilina's riddle

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Catilina's riddle: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Catilina's riddle»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Catilina's riddle — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Catilina's riddle», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

'I was speaking metaphorically, Gordianus,' said Cicero patiently, as if my literal-mindedness were an eccentricity to be indulged.

I took a deep breath and gazed at Minerva, but my equanimity was at an end. ‘I think I must be alone now, Cicero.'

'Of course. I'm sure I can find my way to the door.' He stood up but did not turn away. Instead he looked down at me expectantly.

'Very well,' I finally said. 'Send Tiro around tomorrow morning, if you like, with his writing materials. I shall duplicate Catilina's speech from memory as best I can.' Cicero nodded and turned to go with a smile on his lips. 'And perhaps Tiro will recall Sulla's words more clearly than you do,' I added, and saw Cicero's shoulders stiffen almost imperceptibly.

EPILOGUE

Four years have now passed since Cicero's visit to my new house on the Palatine.

I thought then that the story was finished, as much as such matters can ever be finished. But it seems to me now that recent events have transpired to give a more fitting ending. Like the statue of Jupiter that took years to put in place, it was simply a matter of time.

The intervening years have seen the continued ascendancy of Caesar, who two years ago formed a coalition (or triumvirate, as they call it in the Forum) with Crassus and Pompey, and who last year was elected consul, at the age of forty-one. Now Caesar is off to Gaul, putting down a troublesome tribe called the Helvetii. I wish him well in his military endeavours, if only because my son is with him.

Shortly after our return to Rome, Meto enlisted under the charge of Marcus Mummius, but he didn't care for Pompey, and now serves under Caesar. His choice of a military career baffles me, but I long ago accepted it. (He has always been inordinately proud of the battle scar he received at Pistoria.) In his latest letter, posted from the town of Bibracte in the land of the Aedui, Meto writes of going into battle against the Helvetii with an account that makes my hair stand on end. How did the winsome little boy I adopted ever grow so inured to the sight of blood and gore? Before the engagement began, Meto writes, Caesar had all the horses sent out of sight, beginning with his own, thus placing every Roman in equal danger — a gesture familiar to me from my one experience of battle under a less fortunate commander. Meto assures me that Caesar is a military genius, but this is hardly reassuring to a father who would prefer a son humble and alive to one covered with glory and dead.

I write to him often, never knowing if my letters will reach him. The battle at Pistoria made us closer in a way, even as it widened the gulf between us. It is easier to open my heart to him in a letter, addressing myself to the image of him I conjure up from memory, than to speak to him face to face. My greatest fear is that I may be writing words to a young man already dead, without my knowing it.

I append copies of two of my letters to him written some months apart, the first from the month of Aprilis:

To my beloved son Meto, serving under the command of Gaius Julius Caesar in Gaul, from his loving father in Rome, may Fortune be with you.

The night is warm, and made even warmer by the heat radiating from the flames which shoot up from a burning house nearby.

Let me explain.

A little while ago I was minding my own business, reading in the garden by the last of the daylight. I noticed that the darkening sky had an oddly reddish tinge, but this I attributed to a florid sunset. I was about to call for a lamp when a slave came to say that I had a caller, and our neighbour Marcus Caelius burst into the garden asking if I could see the fire from the terrace upstairs. Together we rushed to my bedroom, where Bethesda already stood transfixed on the terrace, watching Cicero's house go up in flames.

A few days ago Cicero fled into exile, hounded out of the city by the populist tribune Clodius. The reaction against Cicero has been building for some time. There are still those who praise his virtue and his service to Rome, but even many of his staunchest supporters have grown sick of hearing him go on and on about how sharp and fearless he was in putting down Catilina, in such overblown terms that it's become something of a joke. And then of course his overweening vanity and rudeness have become legendary. Crassus despises him, Pompey barely tolerates him, and you know the sentiments of your beloved commander, Caesar. And of course there are a great many people of all classes who sympathized with Catilina without ever joining him, who are rankled by Cicero's constant boasting and his vilification (beyond the grave!) of a man they respected.

As tribune, Clodius has been a genius at organizing the people (the Master of the Mob, they call him) and at cowing (even terrorizing) the Optimates. They say his feud with Cicero began as a personal matter (incited by Cicero's wife Terentia, who accused Clodius's sister of trying to break up her marriage by going after Cicero — imagine!), but soon enough Clodius found he could whip up a firestorm of popular support by making public attacks on Cicero. To elicit sympathy, Cicero let his hair grow and went about the city dressed in mourning, but Clodius and his mob followed him everywhere, jeering at him and pelting him with mud, and the hordes of sympathizers Cicero expected to rush to his defence never materialized. What had become of the masses who had hailed him as Father of the Fatherland only a few years before? The mob is fickle, Meto.

Cicero grew so fearful for his life that he fled from the city, whereupon Clodius got the people's Assembly to pass an edict condemning Cicero to exile 'for having put Roman citizens to death unheard and uncondemned' and forbidding anyone within five hundred miles of Rome to give him shelter. (Never mind the law the Senate passed promising everyone immunity after the conspirators were executed.) Further, it was decreed that anyone agitating to bring Cicero back from exile should be regarded as a public enemy, 'unless those whom Cicero unlawfully put to death should first be brought back to life.' Clodius has a dry sense of humour.

So now, with Cicero headed for Greece, Clodius is on a rampage, and Cicero's lovely house on the Palatine is going up in flames. I write to you not by lamplight, but by the bright, flickering flames that illuminate my bedroom and would make it impossible to sleep, even if I were so inclined.

Now, can you tell me a story of fighting the Helvetii as hair-raising as that?

Where all this chaos will lead I do not know, but I doubt that we have seen the last of Cicero; foxes have a way of slinking back to their lairs once the hunters have moved on.

I wish you every blessing of Fortune in your service under Caesar, and each day I pray for your safe return.

Finally, this letter, which bears today's date, the Ides of Sextilis:

To my beloved son Meto, serving under the command of Gaius Julius Caesar in Gaul, from his loving father in Rome, may Fortune be with you.

I have just returned from a trip up north to Arretium. How wonderful to come home to Rome, to the welcome of Bethesda and your little sister Diana, who in a few days will celebrate her twelfth birthday. They send their love, as do Eco and Menenia and the twins, who have become quite uncontrollable. (I should have become a grandfather in my thirties or forties like most men now I fear I'm too old for it!)

But I must tell you what I discovered on my trip to the countryside. I had not been north on the Cassian Way in years; I have avoided that road, not wanting to pass by the farm again, but a bit of business involving a lost necklace and an adulterous wife compelled me to go to Arretium. (If you want to know the details, you shall have to give up soldiering, come home, and take up your father's profession!)

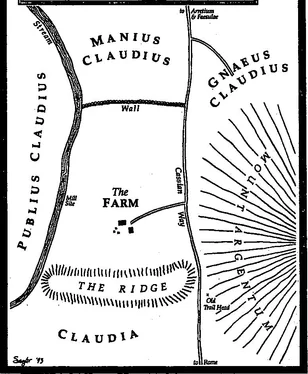

On the way up I was so rushed that I merely rode by the farm at a quick pace. Mount Argentum, the ridge, the farmhouse, the grape arbours and orchards and fields — I felt a pang of nostalgia, which lingered long after I had pressed on. On the way home I had more time, and so when I came to Mount Argentum and the farm, I slowed my horse to a walk.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Catilina's riddle» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Catilina's riddle» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.