“She said they did.”

“She told a great many lies.” We were mounting a gentle hill bathed in pale green moonlight. Ahead of us, seeming as mountains do to be nearer than it was or could possibly be, was the pitch-black line of the Wall. Behind us the lights of Nessus created a false dawn that died bit by bit as the night advanced. I stopped at the top of the hill to admire them, and Dorcas took my arm. “So many homes. How many people are there in the city?”

“No one knows.”

“And we will be leaving them all behind. Is it far to Thrax, Severian?”

“A long way, as I’ve told you already. At the foot of the first cataract. I’m not compelling you to go. You know that.”

“I want to. But suppose… Severian, just suppose I wanted to go back later.

Would you try and stop me?”

I said, “It would be dangerous for you to try to make the trip alone, so I might try to persuade you not to. But I wouldn’t bind or imprison you, if that’s what you mean.”

“You told me you’d written out a copy of the note someone left for me in that inn. Do you remember? But you never showed it to me. I’d like to see it now.”

“I told you exactly what it said, and it’s not the real note, you know. Agia threw that away. I’m sure she thought that someone—Hildegrin, perhaps—was trying to warn me.” I had already opened my sabretache; as I grasped the note, my fingers touched something else as well, something cold and strangely shaped. Dorcas saw my expression and asked, “What is it?” I drew it out. It was larger than an orichalk, but not by much, and only a trifle thicker. The cold material (whatever it was) flashed celestine beams back at the frigid rays of the moon. I felt I held a beacon that could be seen all over the city, and I thrust it back and dropped the closure of my sabretache. Dorcas was clasping my arm so tightly that she might have been a bracelet of ivory and gold grown woman-sized. “What was that?” she whispered. I shook my head to clear my thoughts. “It isn’t mine. I didn’t even know I had it. A gem, a precious stone…”

“It couldn’t be. Didn’t you feel the warmth? Look at your sword there—that’s a gem. But what was that thing you just took out?”

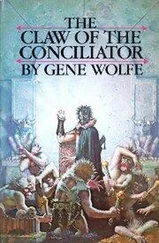

I looked at the dark opal on the pommel of Terminus Est. It glowed in the moonlight, but it was no more like the object I had drawn from my sabretache than a lady’s glass is like the sun. “The Claw of the Conciliator,” I said. “Agia put it there. She must have, when we broke the altar, so it would not be found on her person if she were searched. She and Agilus would have got it again when Agilus claimed victor-right, and when I didn’t die, she tried to steal it in his cell.”

Dorcas was no longer staring at me. Her face was lifted and turned toward the city and the sky-glow of its myriad lamps. “Severian,” she said. “It can’t be.” Hanging over the city like a flying mountain in a dream was an enormous building—a building with towers and buttresses and an arched roof. Crimson light poured from its windows. I tried to speak, to deny the miracle even as I saw it; but before I could frame a syllable, the building had vanished like a bubble in a fountain, leaving only a cascade of sparks.

It was only after the vision of that great building hanging, then vanishing, above the city, that I knew I had come to love Dorcas. We walked down the road—for we had found a new road just over the top of the hill—into darkness. And because our thoughts were entirely of what we had seen, our spirits embraced without hindrance, each passing through those few seconds of vision as if through a door never previously opened and never to be opened again. I do not know just where it was we walked. I recall a winding road down the hillside, an arched bridge at the bottom, and another road, bordered for a league or so by a vagabond wooden fence. Wherever it was we went, I know we talked about ourselves not at all, but only of what we had seen and what its meaning might be. And I know that at the beginning of that walk I looked on Dorcas as no more than a chance-met companion, however desirable, however to be pitied. And at the end of it I loved Dorcas in a way that I have never loved another human being. I did not love her because I had come to love Thecla less—rather by loving Dorcas I loved Thecla more, because Dorcas was another self (as Thecla was yet to become in a fashion as terrible as the other was beautiful), and if I loved Thecla, Dorcas loved her also.

“Do you think,” she asked, “that anyone saw it but us?” I had not considered that, but I said that although the suspension of the building had endured for only a moment, yet it had taken place above the greatest of cities; and that if millions and tens of millions had failed to see it, yet hundreds must still have seen.

“Isn’t it possible it was only a vision, meant only for us?”

“I have never had a vision, Dorcas.”

“And I don’t know whether I’ve had any or not. When I try to recall the time before I helped you out of the water, I can only remember being in the water myself. Everything before that is like a vision shattered to pieces, only small bright bits, a thimble I saw laid on velvet once, and the sound of a small dog barking outside a door. Nothing like this. Nothing like what we’ve seen.” What she said made me remember the note, which I had been searching for when my fingers touched the Claw, and that in turn suggested the brown book, which lay in the pleat of my sabretache next to it. I asked Dorcas if she would not like to see the book that had once been Thecla’s, when we found a place to stop. “Yes,” she said. “When we are seated by a fire again, as we were for a moment at that inn,”

“Finding that relic—which of course I will have to return before we can leave the city—and what we have been saying too, remind me of something I read there once. Do you know of the key to the universe?”

Dorcas laughed softly. “No, Severian, I who scarcely know my name do not know anything about the key to the universe.”

“I didn’t say that as well as I should have. What I meant was, are you familiar with the idea that the universe has a secret key? A sentence, or a phrase, some say even a single word, that can be wrung from the lips of a certain statue, or read in the firmament, or that an anchorite on a world across the seas teaches his discipIes?”

“Babies know it,” Dorcas said. “They know it before they learn to speak, but by the time they’re old enough to talk, they have forgotten most of it. At least, someone told me that once.”

“That’s what I mean, something like that. The brown book is a collection of the myths of the past, and it has a section listing all the keys of the universe—all the things people have said were The Secret after they had talked to mystagogues on far worlds or studied the popul vuh of the magicians, or fasted in the trunks of holy trees. Thecla and I used to read them and talk about them, and one of them was that everything, whatever happens, has three meanings. The first is its practical meaning, what the book calls, ‘the thing the plowman sees.’ The cow has taken a mouthful of grass, and it is real grass, and a real cow—that meaning is as important and as true as either of the others. The second is the reflection of the world about it. Every object is in contact with all others, and thus the wise can learn of the others by observing the first. That might be called the soothsayers’ meaning, because it is the one such people use when they prophesy a fortunate meeting from the tracks of serpents or confirm the outcome of a love affair by putting the elector of one suit atop the patroness of another.”

“And the third meaning?” Dorcas asked.

Читать дальше