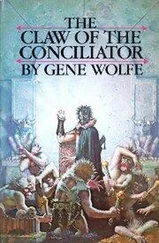

“It’s the Cathedral of the Pelerines—some call it the Cathedral of the Claw. The Pelerines are a band of priestesses who travel the continent. They never—” Agia broke off because we were approaching a cluster of scarlet-clad people. Or perhaps they were approaching us, for they seemed to me to have appeared in the middle distance without warning. The men had shaven heads and held gleaming scimitars curved like the young moon and blazing with gilding; a woman with the towering height of an exultant cradled a sheathed twohanded sword: my own Terminus Est. She wore a hood and a narrow cape that trailed long tassels. Agia began, “Our animals ran wild, Holy Domnicellae…”

“That is of no moment,” the woman who held my sword said. There was much beauty in her, but it was not the beauty of women who quench desire. “This belongs to the man carrying you. Tell him to set you on your feet and take it. You can walk.”

“A little. Do as she says, Torturer.”

“Don’t you know his name?”

“He told me, but I’ve forgotten.”

I said, “Severian,” and steadied her with one hand while I accepted Terminus Est with the other.

“Use it to end quarrels,” the woman in scarlet said. “Not to begin them.”

“The straw floor of this great tent is on fire, Chatelaine. Do you know it?”

“It will be extinguished. The sisters and our servants are crushing the embers now.” She paused, her gaze flickering from Agia to me and back to Agia again. “In the remains of our high altar, which your vehicle destroyed, we found only one thing that seemed yours, and likely to be of value to you—that sword. We have returned it. Will you now also return to us anything of value to us you may have found?”

I remembered the amethysts. “I found nothing of value, Chatelaine.” Agia shook her head, and I continued, “There were splinters of wood set with precious stones, but I left them where they had fallen.”

The men shifted the hilts of their weapons in the hands and sought good footing, but the tall woman stood motionless, staring at me, then at Agia, then at me once more. “Come to me, Severian.”

I came forward, a matter of three or four paces. It was a great temptation to draw Terminus Est as a defense against the men’s blades, but I resisted it. Their mistress took my wrists in her hands and looked into my eyes. Her own were calm, and in the strange light seemed hard as beryls. “There is no guilt in him,” she said.

One of the men muttered, “You are mistaken, Domnicellae.”

“No guilt, I say. Step back, Severian, and let the woman come forward.” I did as she told me, and Agia limped to within a long pace of her. When she would not come nearer, the tall woman came to her and took her wrists as she had mine. After a moment, she glanced toward the other women who had waited behind the swordsmen. Before I realized what was happening, two of them seized Agia’s gown and drew it over her head and away. One said, “Nothing, Mother.”

“I think this the day foretold.”

Her hands crossed over her breasts, Agia whispered to me, “These Pelerines are insane. Everyone knows it, and if I had had more time I would have told you so.” The tall woman said, “Return her rags. The Claw has not vanished in living memory, but it does so at will and it would be neither possible nor permissible for us to stop it.”

One of the women murmured, “We may find it in the wreckage still, Mother.” A second added, “Should they not be made to pay?”

“Let us kill them,” a man said.

The tall woman gave no indication that she had heard any of them. She was already leaving us, seeming to glide across the straw. The women followed her, looking at one another, and the men lowered their gleaming blades and backed away.

Agia was struggling into her gown. I asked her what she knew of the Claw, and who these Pelerines were.

“Get me out of here, Severian, and I’ll tell you. It isn’t lucky to talk of them in their own place. Is that a tear in the wall over there?” We walked in the direction she had indicated, stumbling sometimes in the soft straw. There was no opening, but I was able to lift the edge of the silken wall enough for us to slip under.

The sunlight was blinding; it seemed as if we had stepped from twilight into full day. Golden particles of straw swam in the crisp air about us. “That’s better,” Agia said. “Wait a moment now and let me get my bearings. I think the Adamnian Steps will be to our right. Our driver wouldn’t have gone down them—or perhaps he would, the fellow was mad—but they should take us to the landing by the shortest route. Give me your arm again, Severian. My leg’s not quite recovered.”

We were walking on grass now, and I saw that the tentcathedral had been pitched on a champian surrounded by semi-fortified houses; its insubstantial belfries looked down upon their parapets. A wide, paved street bordered the open lawn, and when we reached it I asked again who the Pelerines were. Agia looked sidelong at me. “You must forgive me, but I don’t find it easy to talk of professional virgins to a man who’s just seen me naked. Though under other circumstances it might be different.” She drew a deep breath. “I don’t really know a great deal about them, but we have some of their habits in the shop, and I asked my brother about them once, and after that paid attention to whatever I heard. It’s a popular costume for masques—all that red. “Anyway, they are an order of conventionals, as no doubt you’ve already discerned. The red is for the descending light of the New Sun, and they descend on landowners, traveling around the country with their cathedral and seming enough to set it up. Their order claims to possess the most valuable relic in existence, the Claw of the Conciliator, so the red may be for the Wounds of the Claw as well.”

Trying to be facetious I said, “I didn’t know he had claws.”

“It isn’t a real claw—it’s said to be a gem. You must have heard of it. I don’t understand why it’s called the Claw, and I doubt that those priestesses do themselves. But assuming it to have had some real association with the Conciliator, you can appreciate its importance. After all, our knowledge of him now is purely historical—meaning that we either confirm or deny that he was in contact with our race in the remote past. If the Claw is what the Pelerines represent it to be, then he once lived, though he may be dead now.” A startled glance from a woman carrying a dulcimer told me the mantle I had bought from Agia’s brother was in disarray, permitting the fuligin of my guild cloak (which must have looked like mere empty darkness to the poor woman) to be seen through the opening, As I rearranged it and reclasped the fibula I said, “Like all these religious arguments, this one gets less significant as we continue. Supposing the Conciliator to have walked among us eons ago, and to be dead now, of what importance is he save to historians and fanatics? I value his legend as a part of the sacred past, but it seems to me that it is the legend that matters today, and not the Conciliator’s dust.”

Agia rubbed her hands, seeming to warm them in the sunlight. “Supposing him—we turn at this corner, Severian, you may see the head of the stair, if you’ll look, there where the statues of the eponyms stand—supposing him to have lived, he was by definition the Master of Power. Which means the transcendence of reality, and includes the negation of time. Isn’t that correct?” I nodded.

“Then there is nothing to prevent him, from a position, say, of thirty thousand years ago, coming into what we call the present. Dead or not, if he ever existed, he could be around the next bend of the street or the next turn of the week.”

Читать дальше