I started learning, as I had never learned before or since. And if I am often scornful of the technical failings of others, it is because I know how hard it is to acquire good technique. I acquired mine by constant labour and study, year after year, day in and day out. It did not come naturally or easily, and it is the one thing I am truly proud of. Naturally I protect my skill against those who dismiss it as redundant, or old-fashioned. To get what you want—exactly the effect you have in your mind and no other—you have to have mastery, otherwise you are like a man trying to speak English with only a limited vocabulary. Unless you have that range, you end up saying what you can say, not what you mean. And once you do that you begin to tramp the road of dishonesty, persuading first others then yourself that there is no difference between the two.

* * *

PERHAPS IT WAS the show that brought about such a change in you. The Show, I should call it, complete with capital letters, because it was the start of a revolution in our poor little island, was it not? When the gales of revolution, the French revolution, swept over us all, violence unleashed, the reactionaries cast aside and consigned to history, where their poor bodies now rot, a-mouldering. With you as the Robespierre, pulling strings behind the scenes, rewarding some and condemning others to professional death.

Even then, I was struck by your ruthlessness, the way you took control of the various artistic groups, rigged elections so that your creatures became the secretaries, the heads of the hanging committees, stamped out all dissent. The way you wrote manifestos and issued them in everyone’s name. The way you so consistently attacked those who dared disagree with you. Dear me! The polite world of English art had not seen anything like it before; was unprepared for such an assault. Pity the poor person who got in your way. Pity Evelyn, who became an object lesson in the dangers not of opposing you but merely of not supporting you.

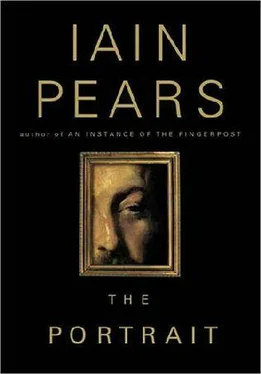

All this must go into my portrait, but it is difficult. In the first picture I caught it, simply because I painted what I saw but didn’t understand what I was looking at. But it is all there, in the way the shadows play across the face, the way I managed to give your eyes that slightly withdrawn, waiting look. Had you asked me at the time, I would have said I was showing up your reticence, a slight fear of the world that you normally hid. I would have congratulated myself on seeing the soft core of your being. But I would have been wrong; what I was painting was your patience; the way you were waiting for the right moment before you launched out; the contempt you had for everyone—painters and critics and patrons—who needed to be disciplined, and controlled. I was painting the burning desire for power curled within you.

And in this second one, I must find a way of depicting power achieved. It would have been easier had you been a general or a politician; then I would have had five hundred years of props to make my point. I could have painted your army at its moment of triumph, and subverted the image by showing the dead and dying in their midst. Or a politician making a speech at the hustings, moulding an audience of the poor and the hungry so that they vote to remain so. Military power, political power, religious power are all well-painted phenomena; each has its attitude and stance and set of the jaw. But a critic? How to depict the power of such a man when I can follow in no giant’s footsteps?

* * *

YOU’RE NOT REALLY interested in how I came to live on this island, are you? At least, it would be unlike you to be so concerned. But I’ll tell you anyway. It will be your punishment for that fatuous politeness you so often affect. It wasn’t planned. I didn’t work out in advance what was the perfect place for me. On the contrary, it took many months of wandering before I got here. Don’t think, by the way, that it marks my submission to your artistic principles, that it demonstrates my acceptance of the French model. Quite the contrary. There is no art here, as you may have noticed. The fads and fancies of Paris are of no more interest to these people than they are to the aldermen of Dundee. Indeed, they think of Paris as an enemy, when they think of it at all. Spending time, energy or money on paintings is all but incomprehensible to them; fighting over it is totally so. They have the sea. It is all they have and all they need.

So I came to a place with no artistic history, where what I do is regarded with blank indifference. I am, I think, the first person ever to wield a brush on this island. There is no predecessor, no artistic colony of like-minded souls, no earnest matrons desperate to have me for tea or dinner. Just the fishermen, their stolid wives, semi-literate children and the sea.

I remember telling you once that I had always wanted to live by the sea. You, of course, thought it was about painting and went on about the possibilities for tactility in the seascape—was that the absurd word you were using then?—in the way the paint could represent light and water. You missed the point, of course. The point was to have all that nonsense washed away. Being by the sea is like a permanent baptism; the light and air hypnotises, and your soul is washed by vastness. You see what true magnificence is, and it is not something that can be put down on a canvas. When you paint, you either represent what you see or project yourself through what is in front of you. Confronted with the sea, you realise the uselessness of both. You cannot humanise the sea. It’s not like all those mountains that are so popular, with merry peasants walking down tracks or harvesting corn. The sea is movement and violence and noise. You remember that Géricault painting, The Raft of the Medusa ? A failure; a cop-out. All these people being heroic and desperate, dominating the canvas, as if they were the point. Put people on the ocean and they are irrelevant and ridiculous, not heroic. They can be swallowed up in an instant and the sea doesn’t even notice. Think of that boy on the beach. But did he paint that? Did he even try to depict the magnificence of it all? No; he twisted it around so that it is yet another tale of people battling terrible odds, of human suffering and courage. How pathetic. The sea is not there for men to be heroes on.

There I go again; I know. But that is why I came here, you know; that is what I was looking for when I left England. It took some time to realise it, of course. I was making it up as I went along. When I took the train from Victoria for the Channel, I thought that I would go south, to the sun and the light, follow in the footseps of everyone else. So I did, for a while. I left my luggage at Boulogne, to be sent after me when I knew where I was going, then headed for Provence. I only stayed a few weeks; there was something in the place that disgusted my Scottish sensibilities. I could feel myself becoming sentimental, even as I stood on the balcony of a hotel in some town whose name I’ve forgotten. Cézanne could do it, no doubt; find the sublime in those people and landscapes. He is the only one of your protegés who is truly remarkable, head and shoulders over the rest of them. In half a dozen little pictures, he changed reality. Provence now looks like a Cézanne painting. It cannot be seen in any other way. Perhaps if I’d never gone to that exhibition of yours, I might have come up with something different, but it would not have been as good, and I was determined not to copy.

Besides, they’ve had it too easy. All they have to concern them is the wind, and they complain about that incessantly. They have never had to bellow their defiance of fate. No-one who drinks wine grown in their own fields has. Besides, what was I to do? Paint bull fights and olive groves? So I moved on, headed for Spain, and stopped in a town called Collioure; stayed there for a few weeks. But the Mediterranean! So blue, so civilised, so warm! None of the ferocity I needed; none of the battle or the terror that the sea should have. At least there I learnt what I was looking for, so it wasn’t a wasted voyage. It’s a poor place, benighted and grim, and I thought when I arrived that it would be perfect. I stayed in a cheap hotel for a week, and found it very peaceful. The people have their own particular inbred beauty, but it is a civilised place, really, if you scrape a little below the poverty and the hardship. That “but” is important. There is a good stone port, and castle, a handsome church, a hotel, some shops—all too much. I got so far as negotiating to take a little house in the village, and thought I would be happy there. So I would have been; that was the trouble. The night before I was due to move in, I walked along the quayside; cloudless night, stars twinkling, a warm wind coming in off the sea, and I felt this strange panic sweep over me. I wasn’t looking for happiness.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу